Canadian LNG expansion does not make sense, regardless of U.S. LNG pause

Key Findings

The U.S. LNG export facility permitting pause should not be viewed as an opportunity for Canada to accelerate natural gas development.

A massive increase in LNG export capacity over the next few years is expected to create a global glut of LNG supply.

Factors like nuclear restarts in northeast Asia and energy restructuring in Europe are reducing gas demand.

Facing looming oversupply and slower global LNG demand, Canada should reconsider accelerating LNG development.

Last month, the U.S. government announced that it would pause authorizations for new liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports to countries without a free trade agreement with the United States. The decision, which effectively pauses approvals of all new LNG export projects in the United States, was spurred by a need to re-evaluate the industry’s effects on American consumers and the environment.

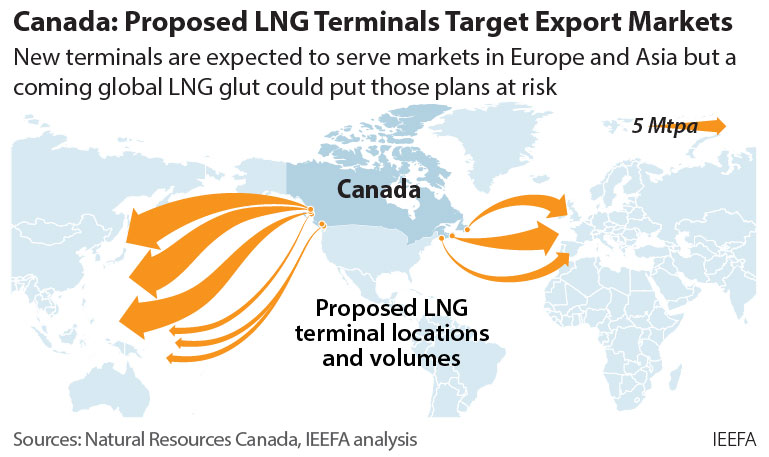

The U.S. decision has had knock-on effects in Canada, where industry groups have argued that the pause creates an opportunity for Canadian LNG export facilities to play a larger role in the global market. This is merely a distraction. Despite the U.S. pause, Canadian LNG projects face an unstable future with increasing market risk, given the dwindling prospects for global demand growth and looming oversupply.

The U.S pause does not apply to existing or already approved facilities. It remains the largest exporter of LNG in the world. With its current capacity of 12.3 billion cubic feet per day already projected to almost double by 2028, the United States will continue to produce an abundance of LNG to supply global markets. Other major suppliers, such as Qatar, plan to boost production and are currently building massive new projects. The LNG Canada project in Kitimat, B.C., set to come online in 2025, will be joined by projects in Mexico, the Republic of Congo, Mauritania, Russia, Australia, and Gabon. By 2026, the world could see a 13% increase in LNG supply capacity—the largest annual increase in history. IEEFA is anticipating a global LNG glut in the latter half of this decade.

Considering lead times for constructing currently proposed projects in Canada, exports from these terminals will have to navigate a global market awash with LNG.

Barriers to Asia’s demand growth undermine the need for new West Coast export projects

Deliveries to China, the world’s largest LNG importer, could face headwinds as renewables are set to do the heavy lifting in reducing coal use. Implementation of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan production and storage targets will reduce LNG import requirements, and its gas utilisation policy could limit gas demand growth and import dependence. The share of natural gas in China’s power mix has remained at just 3% since 2015, while the share of solar and wind has quadrupled to almost 16%, according to EMBER.

Traditional LNG markets are indicating the start of a structural decline in demand. Japanese LNG imports fell 8% last year, and IEEFA estimates that they could fall by one-third by 2030 due to nuclear restarts, higher renewable output, and a declining population. Such decline may leave utilities with excess supplies of LNG. In South Korea, LNG demand fell 5% in 2023, and the country’s climate and energy targets could cause demand to plummet another 20% by the mid-2030s.

Recent price volatility and supply disruptions have spurred developing Asian economies to second-guess the role LNG can play in their future energy mix. In 2023, for example, Pakistan announced it would no longer build new LNG-fired power plants due to volatility in global markets. Both the Philippines and Vietnam have yet to secure a long-term LNG purchase contract. These market realities undermine the assumption that Asian economies are a guaranteed market for exports from British Columbia.

Structural changes to Europe’s energy economy raise doubts about LNG’s long-term role

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the immediate priorities of European Union leaders were to limit purchases of Russian energy, secure alternate supplies, and curb domestic demand. Domestic measures such as applying energy efficiency standards, incentivizing energy-saving practices and promoting improved insulation were introduced. The EU also embarked on more structural initiatives like the REpowerEU plan—a €300 billion initiative to boost the adoption of renewables in regional energy portfolios.

These measures have been largely successful, with EU gas demand falling by 20% since 2022 and electricity demand dipping 6.4% below 2021 levels. For the first time, the renewable share of power generation in the bloc reached 44%, driven by increasing adoption of wind and solar. EU renewable energy capacity is expected to double between 2022 and 2027; 18 of 27 member states broke solar capacity milestones last year. Europe’s long-term LNG demand is now forecast to decline through at least 2030 and likely beyond. Canada’s attempt to develop a costly, long-term LNG infrastructure to address short-term market disruptions is imprudent and could very well be a pathway to stranded assets.

An oversupply and slowing demand mean an acceleration of Canadian LNG supply is not required

Advocates of Canadian LNG developments have exaggerated the impact of the U.S. permitting pause, claiming it provides an opportunity for Canadian exports. However, this view is not supported by market fundamentals.

If anything, the timing of the announcement is instructive. The global LNG market is currently saturated with numerous projects under construction—including five in the United States that are not affected by the pause. Production from such terminals is expected to tip the sector to a position of oversupply by 2025. The demand outlook in Asian growth markets is unclear, while Europe is cutting its gas demand in line with decarbonization goals.

With a high share of uncontracted volumes, proposed Canadian projects are especially vulnerable. It makes little sense for Canadian industry to aggressively push more LNG into the ocean when new supply is not needed, demand prospects are dwindling, and buyers are unsure of their long-term needs.