The U.S. pause on LNG export permits does not threaten energy security in Europe and Asia

The Biden administration’s decision to temporarily pause permitting for new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals has caused an uproar among industry groups and fossil fuel companies. In Congressional hearings on the issue this week, opponents of the move repeatedly declared it would hurt U.S. allies in Europe and Asia that “desperately” need American LNG.

However, these claims ignore basic trends in global gas markets. In Europe, the role for gas is shrinking rapidly as the continent accelerates its transition to clean energy. LNG demand is falling in Japan and South Korea, which have historically been the U.S.’s largest customers. In emerging Asian markets, the U.S. will struggle to compete with cheaper LNG suppliers.

The largest buyers from new U.S. LNG facilities are not European and Asian consumers at all. Instead, they are large oil and gas traders speculating on their ability to re-sell LNG at a profit. The U.S. pause is therefore about tackling the unfettered, unnecessary expansion of the LNG industry and should not be misconstrued as a threat to global energy security.

Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was a wake-up call for European countries overly dependent on imported natural gas, the majority of which was coming from Russia. As gas prices skyrocketed, diversifying energy sources and reducing gas consumption were necessary to tackle the crisis and ensuring energy security.

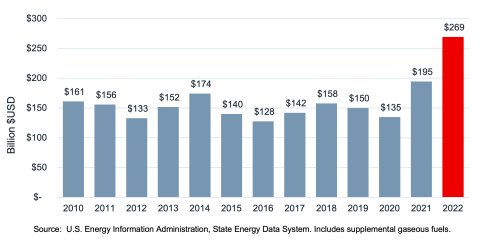

As one of the world’s top three LNG exporters at that time, the U.S. stepped up to break Russia’s grip on European gas supply and help the continent diversify—it more than doubled LNG exports to Europe in each of the last two years compared to 2021.

With global commodity prices reaching record highs in the summer of 2022, however, European countries also implemented energy efficiency and demand management measures while scaling up renewables deployment. As households turned down their thermostats and installed solar panels in record numbers, these strategies started bearing fruit. EU gas demand dropped 14% in 2022 and 7.4% in 2023, and gas storage levels exceeded targets.

As these trends continue, EU gas demand could fall an additional 16% by 2030. IEEFA expects the continent’s LNG demand to peak in 2025—far earlier than U.S. export projects affected by the pause would enter the market.

A closer look at key Asian LNG markets reveals a similarly bleak outlook for proposed U.S. projects. Japan has historically been the world’s largest LNG buyer, but imports peaked in 2014 and dropped 8% in 2023. As generation from nuclear and renewables increases, IEEFA expects that Japan’s LNG demand could fall nearly a third by 2030. Japan’s largest companies have repeatedly acknowledged that they have more LNG than is necessary to meet domestic demand.

South Korea has been the largest buyer of U.S. LNG since 2016. But demand in South Korea dropped 4% in 2023 and could fall 20% by the mid-2030s as renewables displace LNG in the country’s power mix. In the long-term, 2050 net-zero targets in both Japan and South Korea leave no room for unabated natural gas in the energy mix.

In China, LNG demand growth remains highly uncertain given rapidly increasing renewables deployment, as well as higher availability of cheaper natural gas sources. What is clear is that U.S. plays only a small role in supplying China; U.S. exports accounted for just 4% of its total LNG purchases in 2023.

The same goes for potential LNG growth markets in South and Southeast Asia. As LNG demand centers shift to more price-sensitive markets, U.S. LNG exporters will likely struggle to wrestle significant market share from cheaper, geographically closer suppliers in Asia.

Australia, Qatar, and Malaysia supplied over 70% of the Southeast Asian market last year. Meanwhile, Qatar—the world’s cheapest LNG exporter—supplied over 60% of the total imports into South Asia. Qatar aims to massively expand its export capacity this decade, further limiting the upside for U.S. LNG in emerging markets. Recently, countries like Brazil, India, and Bangladesh have looked to purchase Qatari LNG due to its low costs relative to other suppliers.

There is plenty of LNG to go around, as the world is on pace for record increases in global supply this decade. The U.S. has five liquefaction projects under construction that are not affected by the Biden administration’s decision and which would nearly double the country’s export capacity.

Importantly, the largest contracted buyers from these new facilities are not end users in Europe and Asia. Instead, they are oil and gas majors and commodity traders like ExxonMobil, Shell, and Gunvor, which aim to capitalize on resale opportunities. By some estimates, these so-called “portfolio players” have signed on to buy two-thirds of capacity under construction in North America.

As key markets in Europe and Asia cut their dependence on LNG, traders are soaking up an increasing share of U.S. volumes, betting on the long-term growth of the global market. The pause on new U.S. export permits is about reining in how much fossil fuel companies are allowed to gamble.