Shell’s latest LNG outlook underestimates barriers to demand growth in Asia

Key Findings

Shell’s 2024 Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Outlook proves that the long-term investment case for LNG beyond 2040 is fading. Instead, the company is pinning its hopes on rapid demand growth in emerging markets and China’s industrial sector, which may never materialize.

Critical barriers to LNG value chain financing are likely to constrain demand growth in South and Southeast Asian markets. Moreover, LNG is unlikely to provide baseload power generation in emerging Asia due to its high costs compared to other energy sources.

Shell is banking on China’s industrial decarbonization to drive global LNG demand higher, but this overlooks Chinese policies designed to limit gas dependence. Under carbon neutral pathways, China’s industrial gas usage could peak and decline through 2060.

Last week, Shell released its 2024 Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Outlook, a widely read source for the oil and gas industry’s view on LNG market developments.

The report typically serves to justify the company’s own bullish position, but this year’s update contains two surprising findings. First, Shell reduced its global LNG demand expectations for 2040 by up to 11% compared to previous forecasts. More significantly, the company has officially predicted that demand will peak sometime in the 2040s.

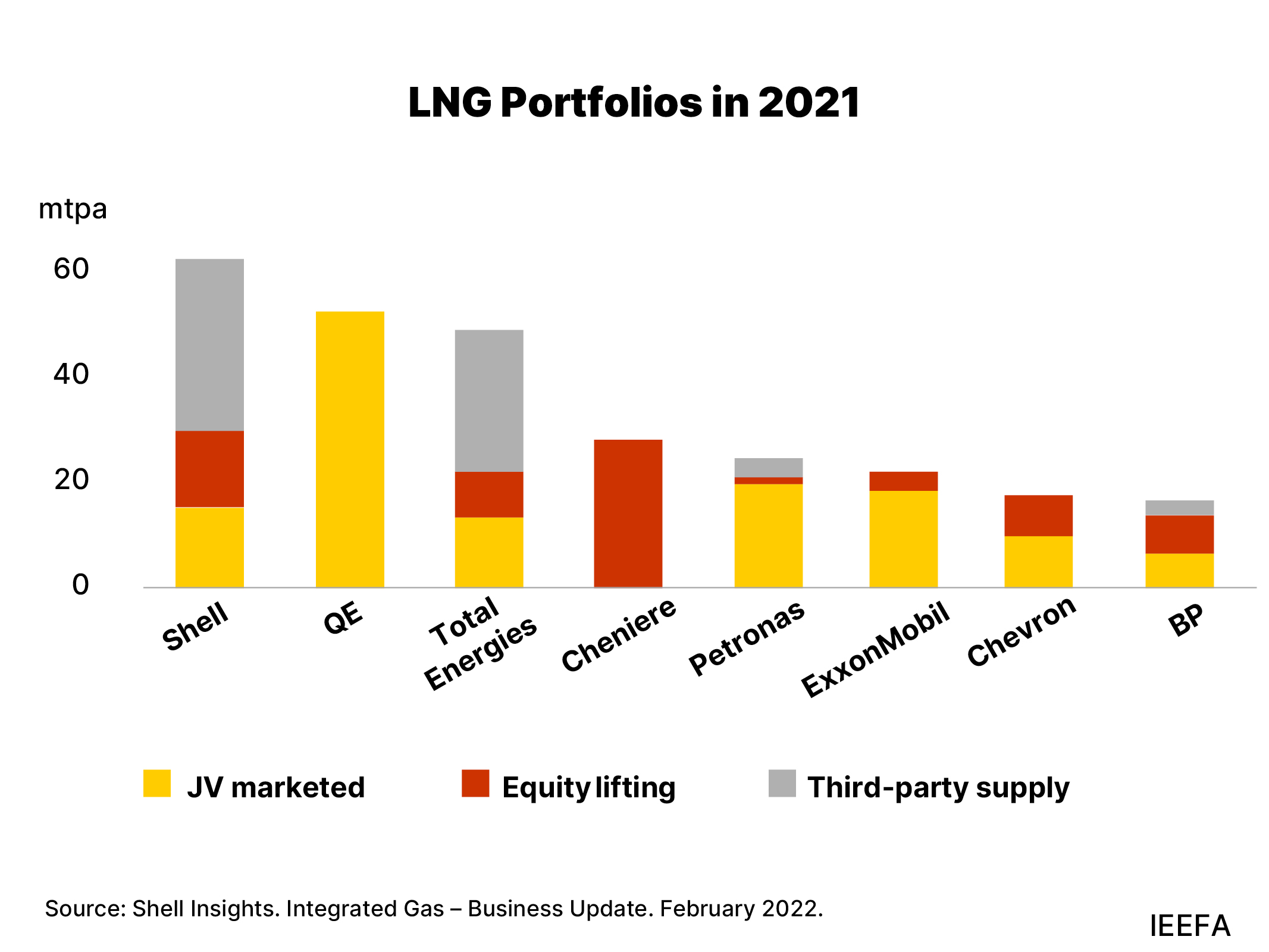

Shell owns the largest LNG portfolio in the world and is one of the largest equity investors in export projects, with assets and contracts that extend beyond 2050. However, its latest outlook proves that the long-term investment case for LNG is fading. Instead, Shell is pinning its hopes on rapid demand growth in emerging markets and China’s industrial sector that may never materialize.

Challenges to LNG penetration in emerging Asia

The outlook acknowledges that gas demand in the mature LNG markets of Japan, South Korea, and Europe peaked last decade. It forecasts instead that South and Southeast Asia will pick up the slack, mainly by using more LNG to generate power.

This will depend on the flow of infrastructure investment, both for import and end-use facilities that do not yet exist. However, Shell’s predictions for breakneck demand growth in these markets underestimate key barriers to LNG value chain financing.

First, LNG-to-power projects take a notoriously long time to negotiate and develop. For example, although Vietnam completed its first LNG terminal in 2023, the country’s first LNG-fired power plant has yet to finalize a necessary offtake contract and could be delayed until 2027. The Philippines has faced repeated contractual issues for gas-fired power plants due to high LNG costs.

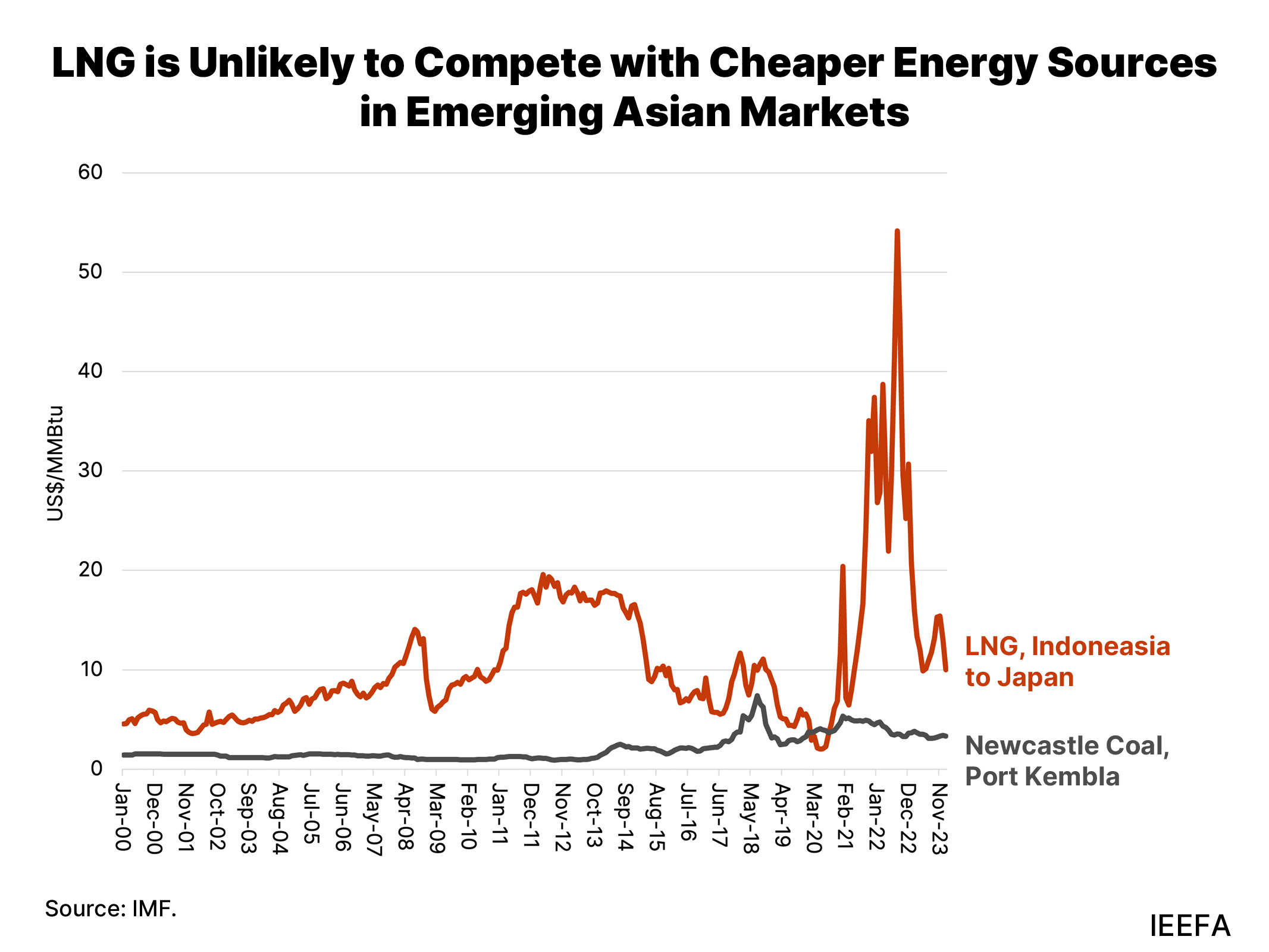

Second, LNG is significantly more expensive than other energy sources, including coal and renewables. Simply assuming that LNG will provide baseload power ignores fundamental economic realities. Bangladesh, for example, faces US$5 billion in outstanding energy payments due to high imported fuel costs.

India’s recent renewal of its oil-indexed LNG contract with Qatar would likely yield LNG prices in the US$10 per unit range. This would need to fall by half to compete with coal imports and even further to compete with cheaper domestically produced resources. As a result, gas is unlikely to play more than a peaking role in much of emerging Asia’s electricity mix.

Third, even in countries like Thailand that have increased imports in recent years, the financial sustainability of LNG remains in doubt. High fuel costs and subsidies in 2022 threw the state-owned utility into a liquidity crisis, and it may be unable to shoulder additional subsidies until 2025. Thailand has instead aimed to ramp up domestic gas production and accelerate its shift to cheaper renewable energy.

China’s industrial decarbonization is not a win for LNG

Shell states that the most important driver of global LNG demand will be China’s industrial decarbonization. This contradicts other pathways for the country’s 2060 carbon neutrality goals already in motion. For example, the International Energy Agency projects that China’s industrial gas usage could be lower in 2060 than current levels. Under an announced policy scenario, China’s overall gas requirements could peak this decade.

Shell’s view overlooks Chinese policies designed to limit gas dependence and mistakenly attributes energy efficiency gains and electrification to gas adoption. China hopes to source over half of its gas supply domestically, and its draft Gas Utilization Policy could constrain coal-to-gas switching. Its decarbonization approach could constrict rather than propel LNG imports.

Shell also asserts that Asia is turning to gas to support renewables deployment and erode coal usage. This is not the case in China, whose 14th Five-Year Plan positions coal as a provider of energy security and power reliability, not LNG.

China has nearly 140 gigawatts (GW) of coal capacity under construction. As the coal fleet increases, utilization will likely fall alongside a meteoric rise in solar and wind capacity, which grew nearly 300 GW combined in 2023.

Since 2015, the share of natural gas-fired generation in China’s power mix has remained at just 3%, while the share of wind and solar has quadrupled to almost 16%, according to Ember data. Clean energy also accounted for the largest share of the country’s economic growth last year. China is clearly not counting on gas to reduce emissions or support renewables deployment.

Ultimately, Shell’s outlook is an admission that the investment case for LNG beyond 2040 is dwindling. Instead, the company is banking on rapid near-term demand growth in emerging markets to fill a gap left by traditional LNG customers. However, high hopes will confront economic realities, meaning Shell’s lower demand forecast this year could be the first of many.