Approaching the Target: SBTi Financial Institutions Net-Zero Standard Comes Into View

Key Findings

The SBTi has developed a comprehensive net-zero standard for financial institutions consistent with a 1.5-degree pathway.

The SBTi framework appropriately outlines the full scope of financial service activities, gives necessary attention to fossil fuel expansion, and focuses on ensuring real economy decarbonization.

The framework, however, should return to a stronger guidance proposed a year ago on the phasedown of fossil fuel exposure.

If the SBTi can maintain a high standard, target validation will not only drive net-zero transition, but also enable financial institutions to showcase their ability to effectively manage climate-related financial risks.

Financial institutions play an important and often underappreciated role in the global push towards a net-zero economy. But without clear benchmarks and standards, it can be hard for stakeholders to distinguish impact from inaction. The Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi), which offered a preliminary net-zero framework focused on financial institutions in June 2023, has released its latest framework draft, and the target is coming into sight.

The draft includes the continued development of a complete set of near- and long-term requirements consistent with a 1.5-degree pathway. Yet there is still more work to do when it comes to closing loopholes, refining definitions, and reversing one unfortunate retreat in an otherwise generally positive revision.

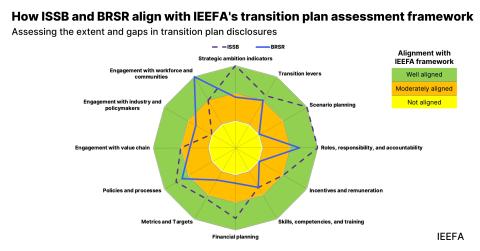

The draft framework begins with a few overarching principles:

-

A meaningful net-zero standard must be integrated into the core of an institution’s operation through public commitments and formal policies.

-

Institutions must commit to robust inventories of their carbon footprint.

-

Clear metrics and targets must be established, aimed at driving financial flows towards net-zero-aligned entities and activities, and away from misaligned ones.

-

Financial institutions should give special attention to certain emission-intensive sectors, especially fossil fuels, due to their importance for the wider energy transition.

-

Institutions need transparent disclosure and reporting so that their net-zero progress can be robustly evaluated.

With these laudable goals, the SBTi’s draft turns to the specifics of implementation. IEEFA welcomes the current draft’s building on the contributions of the last version, providing clear standards for evaluating institutional performance. Most importantly, it gets the big picture right, recognizing that true net-zero alignment requires a shift away from the financing of fossil fuel expansion.

It also clarifies that net-zero plans must apply across an institution’s full range of financial services, considering financed and facilitated emissions from lending, investing, underwriting, and capital market activities. It is right to emphasize the importance of attention to the full coal, oil, and gas value chain, with financial institutions required to disclose their financial exposure to all fossil fuel-related activities and the resulting emissions.

The standards also highlight specific metrics, such as an institution’s fossil fuel-to-renewable financing ratio, which are essential to actionable reporting and benchmarking. And the SBTi should be commended for continuing to make clear that carbon offsets cannot be a shortcut for meeting net-zero goals—emissions reductions must take place in the real economy to count.

Yet there is still more work to do. IEEFA’s latest feedback to the SBTi highlights several areas where attention should next be directed. Although the SBTi notes the importance of developing and publishing a 1.5-aligned climate transition plan, this is currently more suggestion than requirement. This should be made mandatory to prevent inaction: A climate transition plan emphasizes serious transition planning process and implementation efforts beyond policies, detailing exactly how institutions plan to achieve their targets.

As part of the planning, institutions should formulate and implement a transition finance framework. For example, committing to developing and utilizing credible sustainable financing tools such as green- and sustainability-linked bonds is one way to contribute to emission reduction targets. Also, a framework should clarify the institutions’ approaches for financing transitioning entities and activities.

The SBTi’s proposed definition of climate-aligned financing appears to be loose: it may leave some room for investments that fail to demonstrate meaningful progress before 2030, which could create a false impression of real near-term progress in portfolio climate alignment. Also, the SBTi has not provided a clear description of the methods and tools required to delineate transitional activities. As financial regulators increasingly recognize transition planning as a crucial aspect of institutions’ standard risk management, requiring transition plans is essential to reduce risks of transition-washing (misleading information about actual progress) and increase the credibility and usefulness of SBTi-validated targets.

One significant retreat raises concern. The original draft contained outlines of a clear and unambiguous framework to guide the phasedown of fossil fuel exposure—the principle that institutions may attempt engagement to bring fossil fuel producers in line, but that they should “phase out [their exposure] at the latest after two years if their engagement efforts fail to bring the project/company into alignment.”

The current draft weakens this considerably. Although phaseout language is still present, it applies in its most explicit form only for coal (and with a significantly more flexible timeline). Institutions are expected to cease financial flows to new “long-lead-time" oil and gas, but they are left guessing on how exactly to apply net-zero commitments to existing oil and gas exposure.

This omission hinders institutions’ ability to mitigate risk and manage the transition. As IEEFA research has demonstrated, exit is an integral part of any substantive stewardship process. A failure to put it on the table weakens one’s overall climate-preparedness toolkit. The simplest possible solution would be for the initiative to restore the first draft’s phaseout guidance in full. IEEFA also notes that the definition of fossil fuel companies now includes those with a revenue of as much as 10% from fossil fuel activities, having weakened from the last proposal of 5%. A stricter and consistent threshold is crucial to ensure an accurate reflection of fossil fuel exposure.

But even if the work is not yet done, this draft nonetheless marks an important contribution. By working to clarify the principles and metrics behind a meaningful climate commitment, the SBTi continues to meaningfully advance the net-zero discourse. Once refined and implemented, IEEFA expects that target validation will showcase the strengths of financial institutions while enabling stakeholders to monitor and manage climate-related systemic financial risks. With continued improvement, the standards will be able to provide financial institutions with pragmatic and actionable guidance on navigating a lower-carbon future. The target is in sight, and it is now up to the SBTi to finish the job.