IEEFA Update: Norway Shows What to Do With Fading Oil and Gas Holdings

In recommending last week that oil stocks be excluded from its equity benchmark index, Norges Bank, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) manager, has moved oil stocks from a mainstream investment to a speculative grade risk.

If Norway’s Finance Ministry and Parliament agree, GPFG will still invest in oil and gas stocks, but under different terms and at a reduced level. GPFG holds 4 percent of its fund, about $36 billion, in oil stocks with additional amounts in corporate bonds and approximately $36 billion in Norway’s Statoil.

Mindy Lubber, the executive director of CERES, a sustainability think tank, calls the Norges move a “shot heard around the world.” We concur.

Investment funds use indexes to efficiently invest large amounts of money across thousands of companies. The Norwegian Fund uses the FTSE index, and, for this recent analysis, the MSCI World Index Fund, as a proxy for its holdings. Most broad indexes include oil stocks.

Takeaways from the Norges Bank decision:

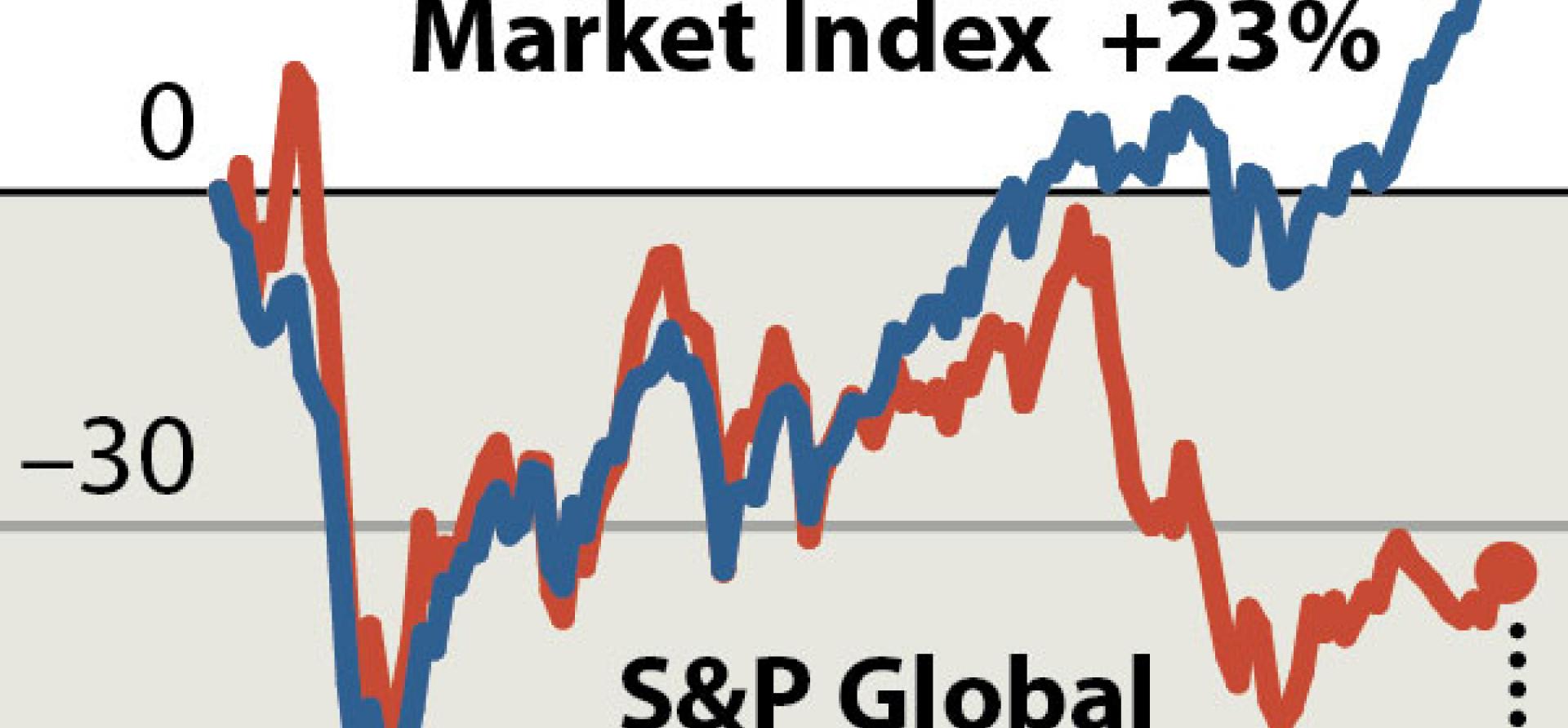

First, the bank has concluded that overall performance will improve by ridding the fund of this whole sector of financial laggards. A comparison by the Bank of the performance of an index of just oil stocks and of five large oil companies—Exxon Mobil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron and Conoco Philips—against the broad equity market tells the story. Since the 1970’s, oil and gas stocks drove the equities market; they led most indexes up in good times and down in bad.

That dynamic has changed, as shown in the chart here. Instead of correlating with the broader stock market, oil and gas stocks have “decoupled.” So while the stock market has been rising, oil prices and stocks are declining. And it is the consensus within Norway that the current low oil price environment will continue through 2060.

Second, Norway’s budget depends on oil revenues, so it reasonably applies a fiscal stress test to its oil investments, which is a tighter standard than the usual market analysis. Standard indexes and financial analysis adjust gradually, based on a long-term historical based approach. Money managers who advise pension funds usually defend their inaction in the face of whole sectors in decline with genuflections to market theories that support passive investment and bemoan the costliness of unwinding carefully planned index strategies. A fiscal stress test looks at the current budget and challenges traditional fund-manager recalcitrance when a government loses revenue—a circumstance that requires undesirable cuts to services and/or tax increases.

Third, there is nothing theoretical about the bank’s recommendation. Norway’s fiscal health is closely aligned with the financial fortunes of the fund. As oil prices and oil equity fortunes decline, so does the ability of the country to meet its annual budget. We’ve published extensive research (“Making the Case for Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment in Renewable Energy Infrastructure” and “How Renewable Energy Holdings Can Contribute to the Growth of Norway’s Pension Fund in a Time of Oil Industry Uncertainty”) exploring the relationship between Norway’s fiscal health and its oil exposure. The Bank and the Finance Ministry agree that action must be taken. Last year was the first in almost 20 years that annual oil revenues were insufficient to cover the fiscal needs of the country. Over the next 40 years, estimates are that the country will have to make annual drawdowns from the principal of its $900 billion fund to make ends meet.

Fourth, with this new approach, the fund is unlikely to continue to apply the typical “Buy and Hold” to oil stocks. Individual companies will be under greater scrutiny and individual decisions can be made about each one.

Fifth, the fund will have more freedom to engage companies on performance or governance issues. When companies are not included in an index, it is no as longer so difficult to sell the stock of those companies, making divestment a real alternative if management refuses to respond.

Money managers and fiduciaries who ignore oil sector trends do so at their peril.

Sixth, the action suggested by the Norges Bank has important implications for fund managers everywhere. We doubt there are any money managers in the world with a better understanding of oil markets than Team Norway. Replacing oil stocks in Norway’s index comes at a time when the fund is raising its asset allocation of equities to 70% from 60%, an increase that will not add oil stocks.

Seventh, while there are those who argue that action is not needed because institutional investors rarely hold significant chunks of any given company, institutional investors in fact hold as much as 4%-5% of their equities in oil and gas stocks and more in bond portfolios (the Norway fund is also exiting high-yield corporate bonds). The $2 billion loss by investors in EnerVest earlier this year reminds us that many funds are invested also in private equity arrangements with oil and gas interests.

Finally, and perhaps most important, institutional investors and proponents of divestment now have a potent new argument for fossil-free portfolios. We argue that while institutional funds do not necessarily have to adopt new strategies immediately, they must prepare.

When a stock or a whole sector that is as significant as oil and gas underperforms for so long a period and with such a negative outlook, fiduciary intervention is necessary. Doing nothing is irresponsible, and money managers and fiduciaries who ignore Norway do so at their peril.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Fact Sheet: Why Norway’s Government Pension Fund Should Invest in Unlisted Infrastructure

IEEFA Report: Winners and Losers Among Big Utilities as Renewables Disrupt Markets Across Asia, Europe, the U.S., and Africa

IEEFA Report: Norway Sovereign Wealth Fund Stands to Gain by Investing Now in Renewable Energy Infrastructure