IEEFA update: Indonesia’s high-risk flirtation with resource nationalism

JAKARTA — Next spring’s presidential and parliamentary elections are fast approaching, and a classic Indonesian pre-election syndrome that combines nationalism and populism has become widely apparent.

As with many countries, Indonesia is dangerously susceptible to such fervor, which can make for questionable policy choices on strategic domestic issues such as infrastructure development and energy affordability.

The next wave of elected officials will want to think hard on these issues, especially as signs of overreliance on the coal industry and state-owned enterprises create serious long-term risks for the Indonesian economy.

If attitudes on display in May at the Asia Coaltrans 2018 conference in Bali were any indication, the potential effects of Indonesia’s energy policy remain badly analyzed. What was most striking about that gathering was how government and business leaders so vigorously embraced the notion of resource nationalism.

Coal is more than just a valuable commodity, goes the core precept in this view; it is the very engine of national industrial development.

That’s an outdated idea, however, although one that seems to be gaining steam in Indonesia even as much of the rest of the world moves beyond coal-fired electricity generation toward cleaner and cheaper renewable energy.

Regulators do their public no favor by blowing hot and cold, and policies that are created strictly around short-term thinking are not in the national interest.

Yet it would be naïve to underestimate the domestic enthusiasm of Indonesia’s coal producers and overseas interests that are eager to bring more coal-intensive industrial projects to Indonesia. It will be interesting to see how the government balances obvious conflicts between burgeoning pro-coal development strategies and its existing commitment to renewables and emissions reductions.

Indonesia has a long history of resource nationalism that can be traced most recently to President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who in essence nationalized foreign-owned mining and mineral companies in 2012. That move was followed by an export ban on raw metals and domestic metal- and mineral-processing to increase the export value of such materials. The intention was to pressure giant U.S. mining companies Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. and Newmont Mining Corp. to build ore-processing smelters in Indonesia.

When President Joko Widodo, better known as Jokowi, took office in 2014, he went even further, promoting the concept of “Indonesia first” with new regulations that required foreign mining companies to sign new licensing agreements before being granted export permits. Jokowi also set about promoting ambitious public works projects goals that included new toll roads, marine ports, airports, and transportation systems. And he announced an aggressive universal electrification plan.

Under this policy, state-owned enterprises, or SOEs, particularly those involved in the energy and infrastructure sectors were expected to become catalysts for economic development. As we have learned from China’s reliance on SOEs, however, state-led infrastructure development doesn’t always pan out as intended.

Indeed, many Indonesian SOEs have struggled to incorporate “social mandates” into project development while generating the profits and shareholder dividends investors expect. Many SOEs, built on risky financing, have struggled just to maintain cash flow.

Xavier Jean, an S&P analyst, noted recently that this trend suggests a weakening among Indonesian construction and power company SOEs on their balance sheets due to the heavy borrowing needed to fund their part of the infrastructure push. Leverage by 20 listed and rated Indonesian SOEs has increased to an average of five times debt-to-EBITDA in 2017, soaring by fivefold since 2011.

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF COAL RESOURCE NATIONALISM AND HIGH-RISK STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISE BUSINESS MODELS, and—more to the point—what risk do their combination of consequences create? The short answer is that they stand to make Indonesia less economically competitive on the world stage, while at the same time requiring more and more state budget subsidies.

PLN, the big Indonesian electricity utility, offers a case study in the problems that Indonesia’s SOEs often face. The country has 2,000 inhabited islands spread across hundreds of thousands of square miles. Accomplishing Jokowi’s 100% electrification target would present a challenge to any company, let alone one like PLN, whose financials and human resources are already far too stretched. With a tariff freeze currently in place, and as fossil fuel prices increase, PLN’s operating losses are growing, and its reliance on government subsidies, as a result, stands to rise sharply (see IEEFA’s recent research brief, “PLN’s Coal IPP Funding Gap Suggests Tariffs Must Rise in 2020”).

Similarly worrying cases include the newly established Indonesia mining industry holding company, PT Indonesia Asahan Aluminum Persero (Inalum), which owns majority shares of PT Bukit Asam, PT Antam, PT Timah, and a minority stake in PT Freeport Indonesia.

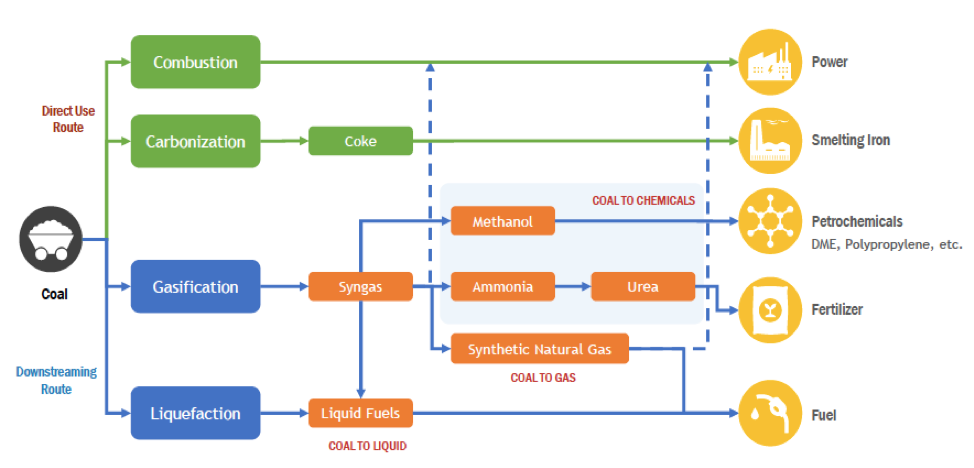

At the Bali coal conference, the CEO of Inalum, Budi Gunadi Sadikin, painted a rosy outlook for more “down-streaming” of coal (see the schematic below), asserting that

Source: Presentation of the CEO of PT Inalum, Budi Gunadi Sadikin in Coaltrans

Source: Presentation of the CEO of PT Inalum, Budi Gunadi Sadikin in Coaltrans

energy-intensive industries require significant baseload, but paying little attention to the fact that mine-mouth power plants are neither cheap nor sustainable under Indonesia’s carbon emission commitments.

Of course, Coaltrans conferences are not known as venues where poorly researched plans are rebutted by expert analysis.

Conversion of low-grade coal into coke, syngas and liquid fuels technology remain processes that are both unreliable and expensive. An IEEFA report published last year (“Using Coal Gasification to Generate Electricity: A Multibillion-Dollar Failure”) found that projects for gasifying coal for power generation have been major failures in the U.S. Of 25 coal gasification electricity generating plants proposed in the U.S. since 2000, only two have been completed. Those plants—both plagued by cost overruns and technological problems—proved economically disastrous for consumers and investors alike.

In Indonesia, the sort of short-sighted planning occurring now risks spiraling debt issues that will only deepen if not carefully managed. In a worst-case scenario, Indonesian SOEs could be forced either to renegotiate their debts and cease all investments or ask for more capital from the government.

That said, some applause is due Indonesian Finance Minister Sri Mulyani, who has been quick to recognize signs that SOEs are piling on too much high-cost debt to their already strained balance sheet. The minister recently announced a new rule prohibiting SOEs from seeking new bank loans, encouraging them instead to prioritize alternative financing strategies such as securitization or bond issues.

WHAT’S CALLED FOR IN INDONESIA NOW IS A SENSIBLE LONG-TERM PLAN to simultaneously accommodate the nation’s needs for infrastructure development and energy affordability—and an open and public discussion around how such a plan will take shape.

Regulators do their public no favor by blowing hot and cold, and policies that are created strictly around short-term thinking are not in the national interest. Thankfully, some in the government are aware of the inherent risks of such policymaking. Bambang Brodjonegoro, the minister of national development planning, for one, has openly and recently urged elected leaders to see beyond their five-year terms, and to endorse wise long-term investment.

Indonesia is blessed with an unusual abundance of natural resources, but if it is to stay globally competitive and to achieve its goal of becoming one of the top 10 economies in the world, it will have to do so through policymaking crafted with a vision that extends past the horizon.

The best outcome will create social and economic prosperity for all, not just for a narrow group of special interests.

Elrika Hamdi is an IEEFA energy finance analyst.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Update: Indonesia’s Electric Company Gets Its Bond Deal Done, But Investor Risk Remains

IEEFA Report: Advances in Solar Energy Accelerate Global Shift in Electricity Generation

IEEFA Indonesia: Coal-Centric State Utility Will Likely Raise Rates by 2020