IEEFA U.S.: A sea change in American offshore wind

The big lease sales ($405 million) last month in coastal waters off Massachusetts for three federally owned tracts that didn’t sell at an auction in 2015 signal a sea change in how U.S. offshore wind generation potential is now perceived.

The winners of that auction, who emerged after 32 rounds of bidding over two days, have global energy-industry pedigrees that bring market-making heft. Equinor Wind is the U.S. arm of the Norwegian oil major formerly known as Statoil. Mayflower Wind Energy is a Shell/EDP Renewables partnership. Vineyard Wind is a joint venture between Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Avangrid Renewables, an American company that is part of the Iberdrola Group, the biggest single owner of renewable energy assets globally.

Much of the momentum around offshore wind is driven by companies with expertise in offshore oil platform activity, an advantage that brings a certain synergy. The industry has proven profitable at scale in Europe after having worked through environmental and fishing-rights complications to become a major piece of the electricity-generation sector. And while U.S. offshore wind remains a mostly untapped resource, that looks like it will be changing soon.

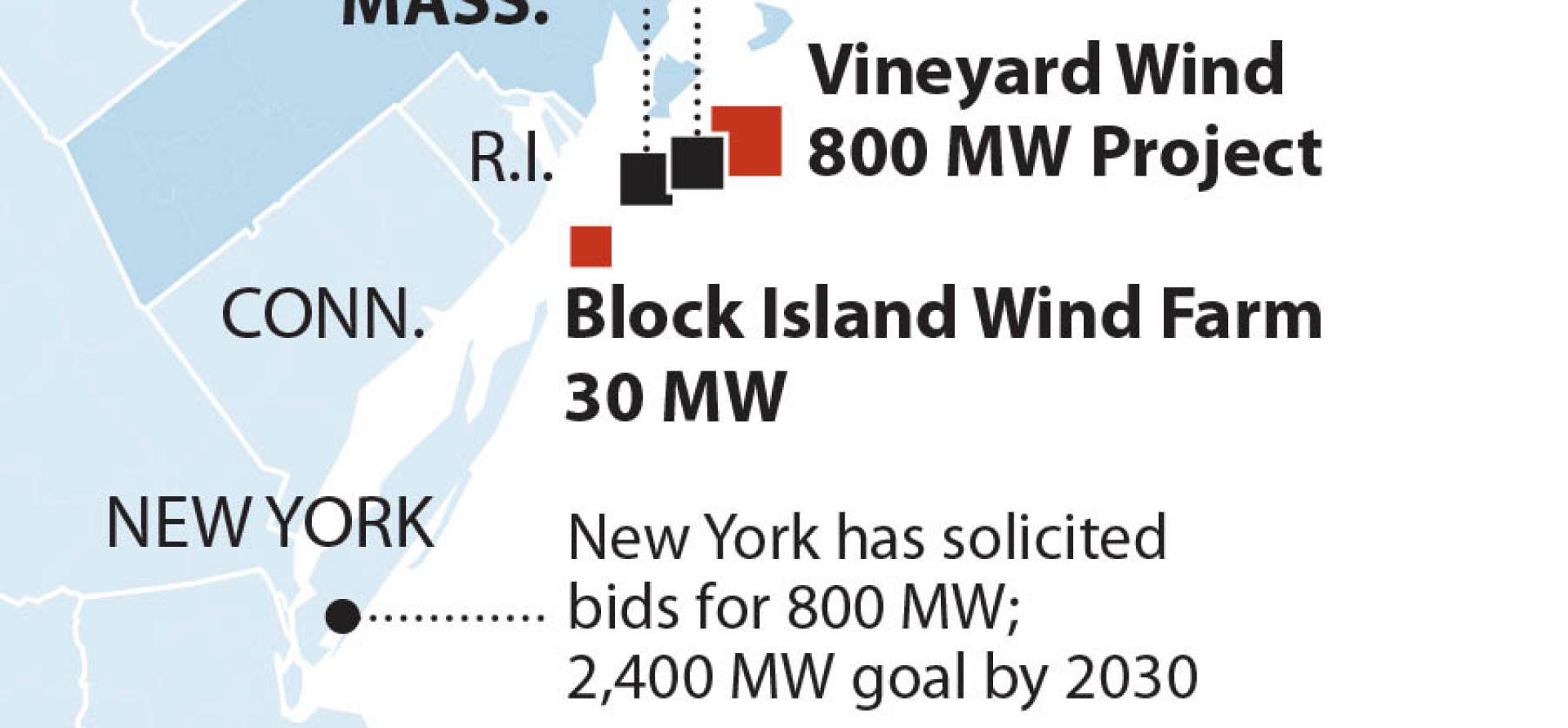

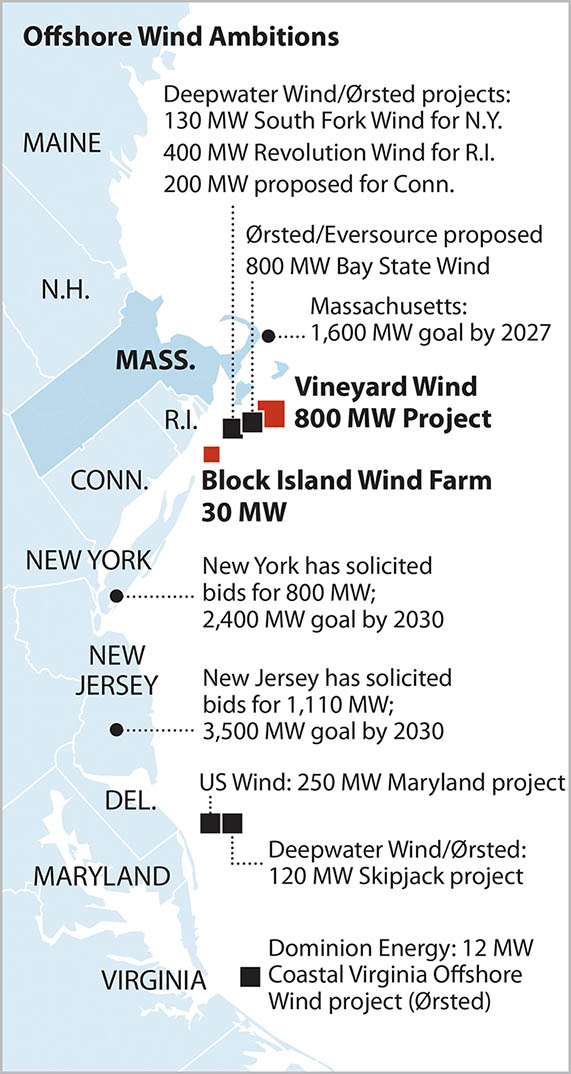

This year, construction is scheduled to begin off Massachusetts on a 160,000-acre, 800-megawatt (MW) project called Vineyard Wind (owned by its eponymous company) that is helping set market trends driven by technology advances and cost advantages. Vineyard Wind has agreed to produce electricity for an average price of 8.5 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) for 20 years, a price that defied most expectations and comes in at about a third of what wind-powered energy costs at Block Island Wind Farm, a small installation that to date is the only operating offshore wind power producer in American waters.

This year, construction is scheduled to begin off Massachusetts on a 160,000-acre, 800-megawatt (MW) project called Vineyard Wind (owned by its eponymous company) that is helping set market trends driven by technology advances and cost advantages. Vineyard Wind has agreed to produce electricity for an average price of 8.5 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) for 20 years, a price that defied most expectations and comes in at about a third of what wind-powered energy costs at Block Island Wind Farm, a small installation that to date is the only operating offshore wind power producer in American waters.

The Vineyard Wind price is striking also relative to New England wholesale power price spikes. The most recent monthly data from ISO New England, the regional grid operator, shows wholesale prices topping 8.5 cents per kWh six times in November alone, exceeding 10 cents three times, and going as high as 16 cents per kilowatt hour.

Massachusetts policymakers are pushing wind power for several reasons: It brings generation diversification and economic benefits and is environmentally friendly, and it can be a buffer against fossil-fuel price volatility.

Awareness around the business proposition for offshore wind is growing state by state through public and private initiatives that are gaining momentum regardless of leadership political leanings, from Texas, already on the vanguard in land-based wind generation, to New Hampshire, where a governor known mainly for his conservative bona fides is now asking for an offshore-wind study.

New Jersey, which elected a transition-minded governor in late 2017, announced a few days ago that it had attracted three bids for developing offshore tracts that would provide 1,110 MW of capacity as part of a program to build 3,500MW over the next decade—enough to power 1 to 2 million homes.

THE POTENTIAL IN OFFSHORE U.S. WIND IS HUGE, according to a joint assessment produced two years ago by the federal Energy and Interior departments. That analysis put it at 10,800 gigawatts (GW) of capacity, which translates to 44,000 terawatt-hours (TWh), something on the order of 14 times current electricity usage in the U.S.

Researchers behind the study acknowledge this is a pie-in-the-sky number, but even when you temper the raw possibilities with economic-feasibility considerations—water depth, windspeed, maritime lanes and fishing rights–a still-epic 2,000GW of capacity remains, or an estimated 7,200TWh of annual generation. The federal Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy estimates, for instance, that if just 1 percent of realistic offshore potential is tapped, it would produce enough electricity to supply 6.5 million households.

The states with the most potential include—no surprise here, perhaps, given the news around last month’s federal lease sales and the Vineyard Wind project—Massachusetts at No. 1, with Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and North Carolina rounding out the top five and South Carolina running a close sixth.

A coastal industry is beginning to take off.

No fewer than 15 other states could build significant amounts of offshore wind-power electricity generation. These include Atlantic Coast states as far north as Maine, as well as the five Gulf of Mexico states. All three Pacific Coast states have major potential as well, though ocean depths there will require solutions different from those that work in shallower waters.

Midwestern states, notably Ohio and Wisconsin, are in the mix as well. Ohio fronts Lake Erie for almost 200 miles, and Wisconsin has more than 800 miles of coastline along Lake Michigan and Lake Superior. Indeed, the Icebreaker Wind Project, a proposed six-turbine array in waters north of Cleveland, has been recommended for approval by staff at the Ohio Power Siting Board.

As the feasibility of offshore wind becomes apparent, governments in states that can benefit are noticing, and the competition is heating up to lure offshore construction companies, turbine manufacturers and a host of support industries. Port communities and states vying for business include Brayton Point, Mass. (a former coal-fired power plant site), the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the Tradepoint Atlantic marine complex in Baltimore and the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority in Ohio.

MAYBE THE BEST-ARTICULATED INITIATIVE ALONG THESE lines comes from the Virginia Offshore Wind Development Authority, created in 2010, which just last week expanded its promotion of a plan to tap long-established port complexes at Hampton Roads, Newport News, Chesapeake, Norfolk and Portsmouth for build-out of an “offshore wind supply chain.”

A state-commissioned study published in December to promote the plan touts the region’s strategic location, its well-developed maritime infrastructure and its skilled workforce. Hampton Roads has historically been the major transshipment point for exports from the fast-declining U.S. coal industry, and the notion that the area can become an East Coast offshore-wind hub is being promoted specifically by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy.

Dominion Energy, a major electricity retailer in Virginia and North Carolina, is partnering with the Danish wind-development giant Ørsted to build a $300 million, 12MW pilot project 24 miles off Virginia Beach. And Ørsted, a sophisticated multinational that is angling for bigger market share and undoubtedly understands development politics, has opened an office in Richmond, the capital, where state energy decisions are made and public policy set.

Karl Cates ([email protected]) is a research editor for IEEFA. Seth Feaster ([email protected]) is an IEEFA data analyst.

Related Items:

IEEFA Georgia: The diminishing importance of coal-fired power generation

IEEFA U.S.: Transition to renewables has taken hold in historically coal-dependent northern Indiana

IEEFA Arizona: Growing interest in developing Navajo utility-scale solar industry