IEEFA Germany: Climate Policy Probably Spells the End of Lignite

Coal is the highest carbon-emitting source of electricity, and lignite the highest carbon-emitting form of coal. Lignite is therefore front and center among risks facing investors from global efforts to slow climate change.

Nowhere is this more true than in Germany, where lignite is still the single biggest source of power generation, accounting for one quarter of the total. But the country has a target to more than halve greenhouse gases by 2030 compared with 1990 levels.

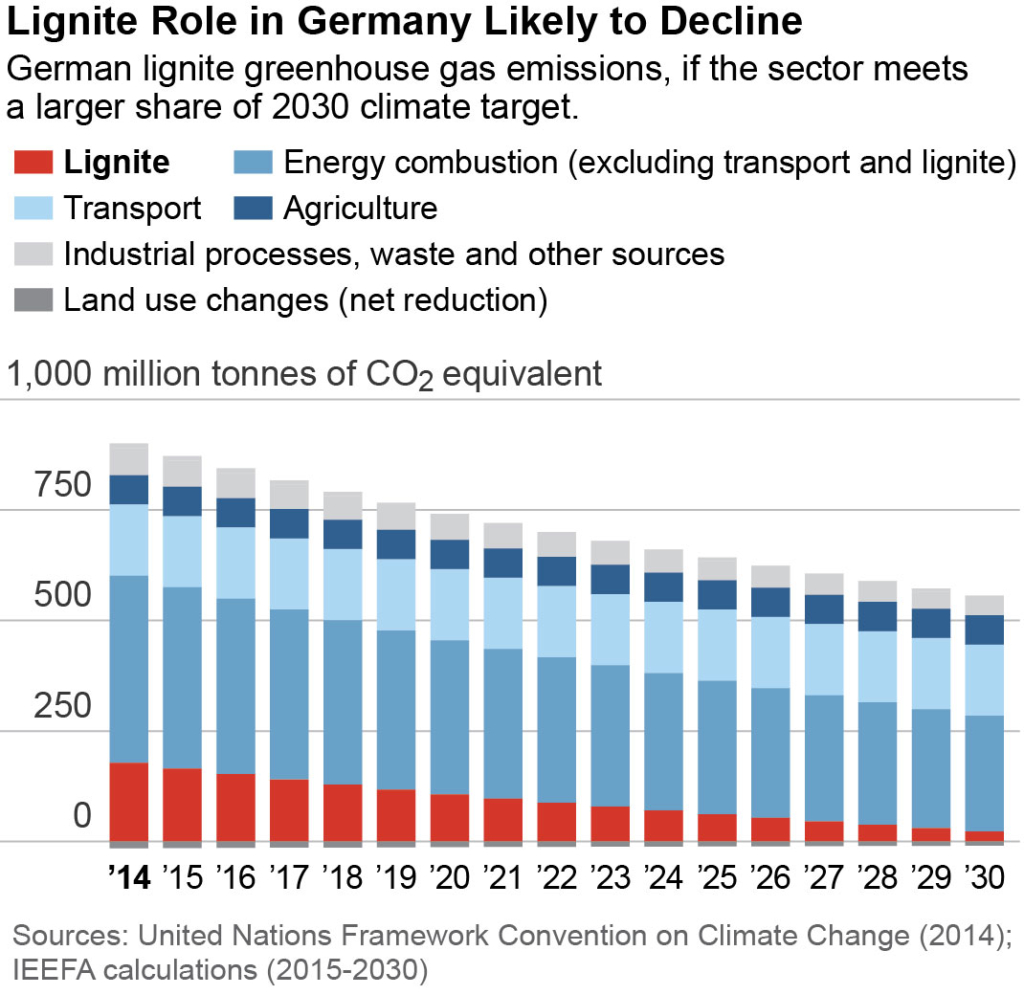

We know that Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions—from data published here by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, here—totaled 885 million tonnes in 2014. Lignite used for generating heat and power accounted for a fifth of that, or 178 million tonnes.

To reach the country’s 2030 emissions goal, total national greenhouse gases would have to fall to 547 million tonnes, or by nearly 40 percent from today’s levels.

What does that mean for lignite?

If we simply adjust the emissions of each sector pro rata, it would mean a 40 percent cut in the lignite fleet.

However, given that lower carbon sources of electricity (gas, renewables and efficiency) are already available and deployed at scale—especially in Germany—it is reasonable to suppose that the power-generation sector will bear a bigger burden of emissions cuts than sectors such as industry, transport, agriculture and land use. And in the power sector, it is reasonable to suppose that lignite will bear the biggest burden of emissions of all because it is the highest source of carbon.

TO ILLUSTRATE, I TOOK GERMANY’S EMISSIONS IN 2014 AND REDUCED EACH SECTOR EQUALLY TO MEET THE 2030 GOAL, except for transport (trains and cars) and agriculture, which I held constant, since cutting emissions at scale in these sectors would be especially awkward. Then, I cut lignite by any remaining shortfall to meet the 2030 target.

The result is seen in the chart here, which shows how lignite emissions must fall under this very reasonable scenario by 87 percent from today’s levels – almost to zero, in other words.

Why, then, have the Czech-based companies EPH and PPF Investments recently agreed to acquire all of Vattenfall’s former lignite assets in the Lausitz region of eastern Germany? Three possibilities come to mind. First, the buyers don’t believe Germany will meet its 2030 emissions target. Second, they believe that another sector, not lignite, will bear the burden of emissions reductions. Third, they expect to be compensated for any forced early retirements of the mines and plants they acquired from Vattenfall (Sweden’s state-owned utility company).

WHICH OF THESE THREE POSSIBILITIES IS MORE LIKELY? IT COULD BE THAT SOME COMBINATION of all three eventualities will occur, but we think chances are especially good that EPH and PPF are making a subsidy play, that is, they are pursuing the third of the three possibilities above. The thinking on the part of EPH and PPF executives is probably that they can get some form of lucrative subsidy in return for agreeing to shut down the lignite mines and power plants over some specific period of time.

This all comes down to a high-stakes game between the Czech interests and the German government, which will want a gradual phase-out of lignite to meet its emissions targets, and one that occurs as the least cost to the energy consumer. To secure government compensation (such as capacity payments, which pay plant owners simply to keep plants online, regardless of whether they are producing), the Czech owners may threaten to abruptly shut down the power plants. This tactic would include arguing that a gradual phase-out would be uneconomic to the new owner, and it would play up the energy security these plants provide in the near term. That said, the new owner could simply also threaten to sue the government, as some energy interests have already done in the case of the forced early retirement of nuclear power plants.

Such brinkmanship is a gamble, and may explain Vattenfall’s eagerness to be rid of the assets. The risk is only complicated, of course, by the €1.5 billion ($1.7 billion) liability for rehabilitating the associated lignite mines, explained in full in an IEEFA report published here last month (here’s an executive summary of that report translated into German).

As we said in publishing that report, there is no need for the German government to subsidize EPH and PPF. In fact, our “Foundation-Based Framework for Phasing Out German Lignite in Lausitz” rules out a taxpayer-funded lignite bailout. It lays a sustainable path forward for Germany to meet its climate goals, and it allows the Lausitz asset owners to operate their power plants profitably through the phase-out period while meeting their cleanup commitments.

Equally important, our proposal allows for much-needed transparency and would help local communities prepare for a future beyond lignite.

Gerard Wynn is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Europe: Blueprint for a Lignite Phase-Out in Germany

IEEFA Europe: Behind Vattenfall’s Sell-Off of German Lignite Assets, a Subsidy Play by the Buyers

IEEFA Europe: ‘Capacity Payments’ Provide a Lifeline to Costly Coal-Fired Generators