IEEFA: ExxonMobil must change direction to thrive

By virtually every measure, the global oil and gas industry had a dreadful 2020. Demand slumped; prices sagged; stockpiles swelled; profits evaporated; and, for the fifth time in seven years, the energy sector ended the year in last place in the stock market.

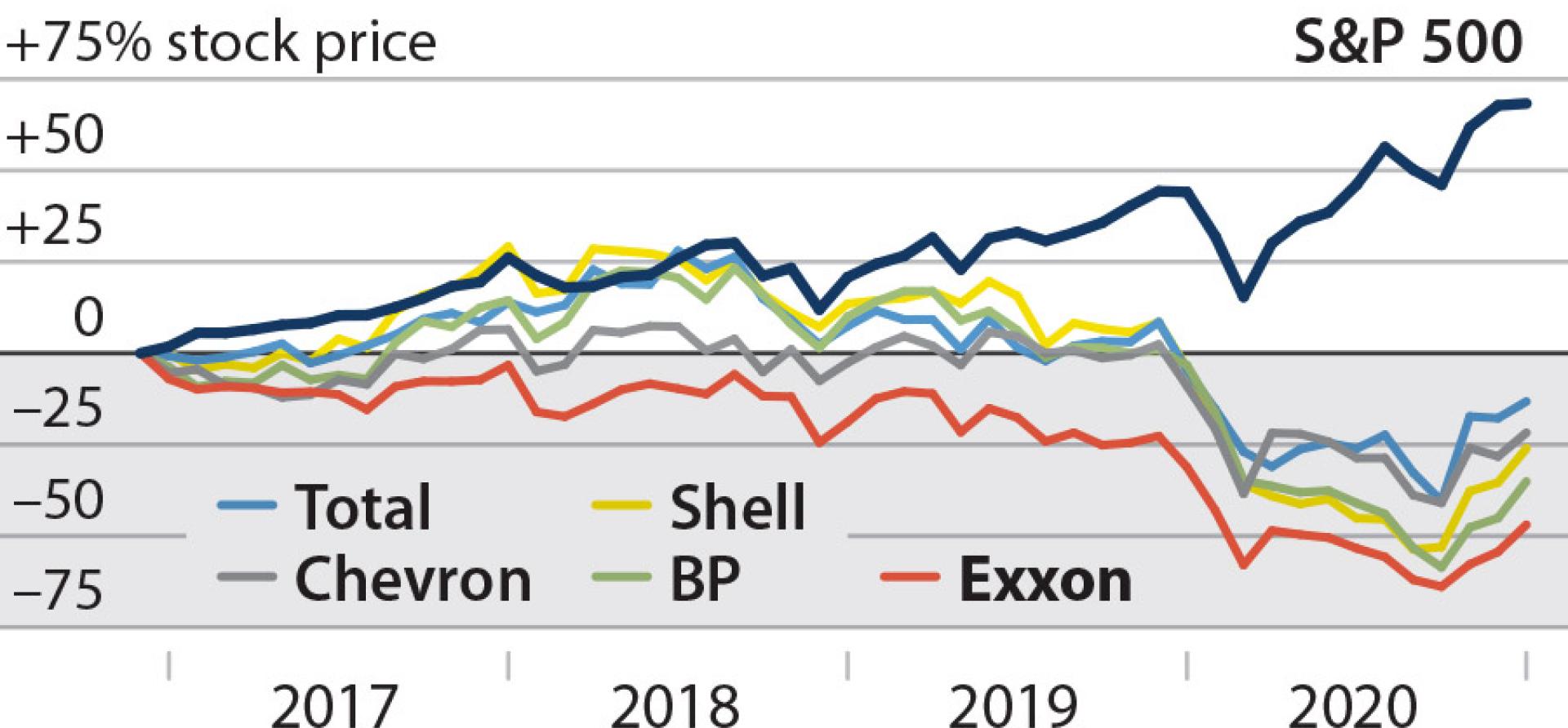

Amid this rout, ExxonMobil stood out for its poor performance. The company’s stock lost 40 percent of its value. It announced unprecedented write-downs while cutting 14,000 jobs. It fell out of the Top 10 of the S&P 500, was booted off the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and its market value was briefly eclipsed by its largest U.S. rival, Chevron.

Amid this rout, ExxonMobil stood out for its poor performance. The company’s stock lost 40 percent of its value. It announced unprecedented write-downs while cutting 14,000 jobs. It fell out of the Top 10 of the S&P 500, was booted off the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and its market value was briefly eclipsed by its largest U.S. rival, Chevron.

But for ExxonMobil, this was simply the continuation of a trend. During the tenure of CEO Darren Woods, the company’s stock has fallen faster and further than other oil and gas majors, destroying tens of billions of dollars of shareholder value.

Last year’s torrent of bad news has now eased a bit. Oil and gas prices have risen, and stock values have moved with them. In the U.S., drilling has ticked up slightly. The industry is by no means thriving, yet rising oil prices should prevent a repeat of last year’s abysmal performance.

Based on recent statements, ExxonMobil’s corporate leaders will likely treat this upturn as a vindication of their business strategy. For decades, that strategy has hinged on a singular view of oil’s trajectory in the global economy: Consumption would rise in lockstep with economic growth. Pinched by rising demand and limited supplies, prices would rise—and companies able to discover and develop oil and gas reserves would eventually generate ample returns.

Economic growth now requires less oil

The last decade proved that this view of oil markets is outdated. Economic growth now requires less oil. Reserves have grown more abundant. Prices have trended downward. A host of competitors and external forces—including ever-cheaper renewables, rising efficiency, plastics recycling, preference for clean energy, growing cooperation on Paris Agreement goals, and a sophisticated global climate movement—are realigning energy markets by eroding oil and gas demand. Combined, these forces undermine both growth assumptions and long-term profits for the oil and gas sector.

Even an increase in oil prices no longer signals long-term financial health for ExxonMobil, or for the industry as a whole. Yes, higher prices will boost short-term cash flows, lift stock prices, and foster a storyline of an industry on the rebound. Yet, rising prices in this period of energy transition now carry growing financial risks for oil companies.

Rising prices now destroy demand. Higher oil and gas prices simply accelerate the energy transition by making renewables and efficiency investments more cost-competitive. Electric cars are already chipping away at gasoline demand. Wind, solar, and battery storage are starting to do the same for natural gas. The alternatives to oil and gas are already inexpensive, and costs continue to fall.

High prices encourage speculation on new oil and gas production. Over the last decade, price upticks spurred oil companies and Wall Street investors to pour billions into capital-intensive oil and gas projects—only to see those investments obliterated when the inevitable oversupply brought prices back down. Investors may have been chastened by these failures; many have pledged to eschew new oil plays. If this discipline holds, new drilling could remain subdued and prices might stay higher for longer. If not, we could see more capital inflows and more production, creating yet another boom-and-bust investment cycle that diverts scarce capital from the much-needed energy transition.

Consumers and importing nations can now fight back against high prices. High prices create a host of ills for the globe’s oil and gas importers, including trade deficits, inflation, currency devaluation, and a weakened investment environment. But consuming nations now have new tools to fight back against high prices. Structured investments in renewable energy can permanently loosen their dependence on imported oil and gas, and a host of policies can redirect capital towards energy alternatives.

Rising prices may give new life to outdated strategies. Each oil uptick has prompted ExxonMobil and like-minded companies to double down on the failed strategy of heavy capital spending on new oil and gas supplies. But until prices rise dramatically and persistently, the oil industry can’t find a sustainable business model in simply depleting and replacing reserves. In 2018, global oil prices stood at $71 per barrel, almost $30 more than in 2020, yet the energy sector still finished in last place in the S&P 500.

Rising prices could lull investors into complacency. The oil and gas industry’s financial woes have galvanized investors into pressing for changes in oil industry governance and strategy. Some companies have responded by diversifying their business models—shifts that were healthy for the companies and rewarded by shareholders. But rising prices could derail this investor pressure, discouraging healthy scrutiny, weakening transparency, and dissipating the momentum of the energy transition.

ExxonMobil has transformed itself from a stock market leader to a laggard

By clinging to its outdated view of energy markets—a view in which price increases were both inevitable and beneficial—ExxonMobil has transformed itself from a stock market leader to a laggard. The business model that failed to sustain the company during bad times will serve just as poorly as prices rise. The company can find no refuge in politics, either. Just look at the past four years: When a “pro-fossil fuel” administration took office in January 2017, ExxonMobil’s market capitalization was $373 billion. Today, it is $204 billion.

Clearly, ExxonMobil needs to adopt new strategies to deal with the reality of today’s energy markets. The process will be uncomfortable. First, the company must acknowledge the core problem with its business model: It is a cash business with a deteriorating asset base. The company’s leaders must then establish a new model that accommodates lower revenues, slower demand growth, competition and falling opportunities for profitable oil and gas investments.

But the management team that brought the company to its diminished state is unlikely to steer it back towards financial success. For ExxonMobil, change must start at the top, with new, clear-eyed leadership able to understand where the winds are blowing in the global energy markets, and willing to tack accordingly.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of financial analysis.

Clark Williams-Derry ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy finance analyst.

Recent articles:

IEEFA update: ExxonMobil’s financials indicate slide under CEO Darren Woods’s leadership

IEEFA: ExxonMobil financial performance slides from industry leader to laggard