IEEFA Asia: International Investors Are Buying Into India Renewables Boom

India requires global financial support to manage the capital-intensive nature of renewable energy infrastructure development. In order to sustain the Indian Government’s bold renewable energy deployment targets, more such support is needed. Indications are this is exactly what’s happening.

India requires global financial support to manage the capital-intensive nature of renewable energy infrastructure development. In order to sustain the Indian Government’s bold renewable energy deployment targets, more such support is needed. Indications are this is exactly what’s happening.

Political support for developing 175GW of renewable energy generation capacity, including 100GW from solar and 60GW from wind, has enabled Indian companies to focus on the renewables sector. State-owned NTPC, the largest electricity generator in India, recently announced plans to become the country’s largest renewable energy company by weighting investment toward renewables and away from thermal coal.

Energy-sector conglomerates that have initiated multiple investment programs in renewables include Adani Power, Tata Power and Reliance Power. In addition, some of India’s wealthiest entities have entered the space, including Aditya Birla Group, Bharti Enterprises and the Dilip family.

However, an estimated US$100 billion investment is required to meet the 100GW solar target alone, and the program is well short of the goal. Adding to the difficulty of achieving such high levels of investment is the cost of capital in India; financing is available but at short tenure and high cost. Attracting foreign investment remains key to meeting India’s ambitious targets.

It is not an intractable problem, though, and signs are the gates are opening. Global development banks like the World Bank have a key role to play as early movers and an initial source of overseas capital in such initiatives—and the World Bank has embraced the role in India. In June, it announced a US$1 billion investment in Indian solar FY2017. This comes on top of an earlier US$625 million investment from the World Bank for the Indian government’s rooftop solar program. In August, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private sector investment arm, disclosed a US$125 million equity investment in Hero Future Energies. This renewable energy company is backed by the diversified conglomerate Hero Group and intends to develop a 2GW portfolio of wind and solar projects by 2020. This comes after the IFC facilitated debt funding of around US$177m to renewable energy company Ostro Energy earlier this year and the Asian Development Bank lent US$175m to Mytrah Energy to fund wind and solar projects.

Private capital has also been flowing to Indian renewables over the past two years, and Bridge to India, an energy consulting firm with offices in New Delhi and Munich, has recently reported promising new deals in India by some of the world’s major energy investors.

Greenko has come to an agreement with SunEdison to buy the latter’s Indian commissioned and solar pipeline capacity, totaling 1.4GW, worth about US$1.2 billion, for a premium of less than US$100 million. This move transforms Greenko into a leading participant in the clean energy industry in India. It’s worth nothing that Greenko’s owners includes GIC (Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund) and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, two of the biggest investors in the world. Meanwhile, Azure Power, an Indian renewables company, plans to sell a minority stake to Canadian asset manager Brookfield, a leading global investor in infrastructure, for US$75 million.

It’s been reported that other overseas investors, including Japan’s Sumitomo Corp are looking for investment opportunities within the Indian renewables sector. Sumitomo could join Softbank Group as a prominent Japanese investor in Indian renewable energy. Softbanks’s joint venture (SB Energy) with Bharti Enterprises Ltd and Foxconn Technology Group of Taiwan pledged US$20 billion of investment in Indian solar in 2015, and SB Energy has won several tenders including a 350MW solar project in Andhra Pradesh.

With coal-fired power projects beset by regulatory issues and delays, it is increasingly likely that Indian solar and wind projects will get the investment support they need. The Andhra Pradesh tariff of Rs 4.63/kWh is typical of new projects coming on in the Rs 4.4 to Rs 4.8/kWh range that make solar cheaper than new imported-coal-fired power projects, which cost Rs 5 to Rs 6/kWh. In addition, the deflationary nature of 25-year solar tariffs with zero indexation, that is, fixed upfront costs and then no energy costs for the life of a project, make solar more attractive.

Indications are, too, of a growing maturity across the Indian renewables space.

The largest deal in the sector, Tata Power’s 2016 purchase of the renewable energy business of Welspun Group for US$1.38 billion, will give Tata Power renewable capacity of 2.3GW, the most of an single company to date in India, a likely sign of more to come.

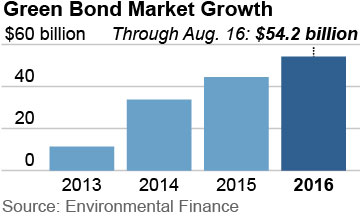

Debt-market transactions completed by Greenko and Tata Power have opened up new financing opportunities with US$500 million and US$525 million raised, respectively. The Greenko issue was into the fast-expanding green bond markets, which topped US$150 billion this month. Already this year, global issuance of green bonds stands at US$54.2 billion and has a shot at exceeding US$100 billion by the end of the year. Last year’s issuance totaled US$44.5 billion, itself a record.

The renewable-energy debt market, once dominated by the supranational development banks, can be an important source of capital on attractive terms for the continued expansion of the Indian renewables sector. With international bond rates of 2-4 percent, significantly lower than the usual 8-12 percent corporate borrowing costs in India, growing utilization of the green bond market will see the capital cost of these projects drop (even allowing for Indian Rupee hedging costs of 3-4 percent).

In addition, Indian corporates now have the option of tapping into the masala bond market (masala bonds are linked to the rupee but issued offshore and settled in dollars). In September 2015, the Reserve Bank of India began to allow Indian corporates to issue Indian rupee-denominated bonds in overseas markets. This allows Indian companies access to alternative, overseas funding without taking on currency risk. NTPC and Adani Transmission are among the companies that have issued masala bonds. With low global interest rates and the prospect of sustained growth across the Indian economy, ratings agencies Fitch and Moody’s expect strong development of the masala bond market.

Meantime, consistent political support for renewables is encouraging more Indian corporations to enter the renewable energy sector. The sector is seen increasingly as a magnet for overseas investment and as a catalyst for renewables growth. It seems India is well on its way toward achieving its renewable energy targets.

Simon Nicholas is an IEEFA research associate.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA India: How $1 Billion in World Bank Lending Is Helping Drive a Solar Boom

Cancellation of 4 Ultra Mega Power Plants Underscores India’s Commitment to Transition

Rapid Energy-Sector Advances in India and China