IEEFA Africa: Is Angola a cautionary tale for Guyana’s oil wealth hopes?

The South American country of Guyana, the latest nation to have discovered commercial reserves of oil and gas, hopes to raise its standard of living, cut its debt, eliminate its deficit and create a sovereign wealth fund. It is in a weak position to accomplish these goals.

Consider the example of Angola, which has hosted world oil developers for the last 25 years and is a cautionary tale for nations hoping to cash in on oil and gas development. Angola is deeply in debt, owing $20 billion to China. Annual budget deficits plague the nation. Its president is offering another round of oil reforms.

Fitch Ratings recently downgraded Angola, noting its economy “continues to be constrained by its high level of commodity dependence, which contributes to low growth and increased macroeconomic instability.” The International Monetary Fund agrees the Angolan economy is hampered by limited diversification.

Guyana is entering the first full year of a multi-decade oil agreement with ExxonMobil, Hess and the China National Overseas Oil Corporation (CNOOC). Last year, the government reported that the company missed its production target due to the pandemic, flaring and technological issues. The Guyanese government hopes initial problems will be worked out and it will be able to secure a prosperous future from its oil reserves.

The Angola experience, however, offers some lessons.

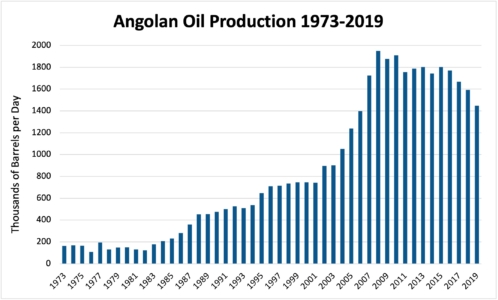

Oil was discovered in Angola in 1955. In the 1990s, deepwater exploration took off and Angola became a global presence. Major oil companies including Total, ExxonMobil, BP, ENI, Chevron and Equinor have successfully drilled for oil in working through Sonangol the nation’s state owned oil and gas operator.

The country produced approximately 1.4 million barrels per day last year, down from peaks of 1.9 million barrels per day. It ranks 15th in the world. President Joao Lourenco is trying to increase production with a new round of offers to the international oil community.

Despite its resources, four decades of oil production have created neither prosperity nor fiscal stability for Angola. At the end of 2020, the national debt stood at approximately $76 billion. The credit rating carries a junk bond status. With the assistance of the IMF, World Bank, African Development Bank and others, Angola has managed to juggle its year-to-year obligations with a combination of refinanced or forgiven debt. Angola recently entered the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiatitve, designed to assist financially distressed countries.

One in 3 Angolans lives below the poverty level, and more than half live on less than $1.90USD per day. An unbalanced economy and corrupt government are cited as major factors driving the economic inequality.

After decades of investment, major oil companies remain interested in Angola. ExxonMobil, for example, has enjoyed a long relationship with Angola. In late 2020, it announced another new discovery and agreement with the country to expand production.

Lourenco, elected in 2017, promised to reform the government’s management of its resources. Reforms designed to develop natural gas reserves, however, may require new investment by Angola at a time when it suffers from a high level of debt.

Rather than increasing the country’s economic independence, oil development has led Angola into a series of traps that include budget deficits, foreign indebtedness, corruption, and oil exploration and development contracts that have benefited corporations at Angola’s expense.

Despite the struggle to introduce new reforms and combat corruption, the lack of economic diversification leaves Angola poorly positioned to handle changes brought on by the energy transition.

Meanwhile, ExxonMobil informed its shareholders last week that the company found more oil in Guyana last year. Guyana is now one of ExxonMobil’s top earners, and revenue from the country helped boost ExxonMobil revenues in a year when the company struggled for cash.

Guyana’s leadership would like to balance its budget, reduce debt, increase spending and establish a sovereign wealth fund. The Guyana contract, however, is a one-sided deal that favors the three companies and creates obstacles to growth that threatens to leave Guyana deeper in debt.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of financial analysis.

Gerard Kreeft ([email protected]) is an energy transition advisor.

Related items

Press release: Oil consortium deal with Guyana far from panacea for country’s ailing finances

Report: Oil consortium deal with Guyana far from panacea for country’s ailing finances