Peabody, a Lost Former Leader, Misses the New-Energy Boat

By Tom Sanzillo

A few years ago, Peabody Energy appeared to have a tough-minded team of savvy, shrewd executives at its helm, hell bent and well on the road toward bringing about a new mega-cycle of global coal development.

In retrospect, that was all an illusion.

The crumbling of Peabody’s image as a well-run company shepherded by smart leaders can be traced probably to late 2010, when Peabody let investors know it thought its Powder River Basin coal reserves, then getting about $14 per ton, were worth more like $30 to $35 per ton and that those prices would be achieved by 2016. Their thinking, presumably, was that the rapid decline of Central Appalachian coal combined with the rise of new export markets would lift coal prices—and profits—to levels never seen before. We were skeptical, but this was Peabody we were talking about.

As the sun sets on 2014, coal is selling for $11 per ton, it looks like another bad year ahead for producers, and that $35 coal seems more and more like a fading mirage.

Peabody’s mistakes haven’t been limited to getting the broader energy markets wrong. They made some bad business deals along the way, too, including a costly failed venture in Mongolia and— despite a lot of upbeat fanfare and the purchase of Macarthur Coal in Australia—adding a mountain of new debt as the markets started to turn in 2011.

Closer to home, we watched with growing concern as Peabody promised scores of Midwestern communities it would bring them cheaper and more reliable electricity by way of the new $5 billion Prairie State Energy Campus. The result of that fiasco is that ratepayers across the region are now saddled with a power plant that is too expensive to run and that is setting off a grassroots backlash.

Sadly, Peabody continues to insist Prairie State is a resounding success, even as it has brought Mark Crisson, the former head of the American Public Power Association, out of retirement to preside over the company’s handling of the deep public crisis it has helped create in Paducah, KY., a city whose economy is being steadily crippled by its costly commitments to Prairie State. High-priced Prairie State electricity, in the meantime, continues to erode the economic future of many communities like Paducah. Lawsuits have been filed and more may be forthcoming. The SEC has issued subpoenas.

Of late the company has gone on a global PR blitz with its “energy poverty” campaign, arguing that the only way many undeveloped parts of the world will ever have access to electricity is through a worldwide build-out of coal plants. Few analysts are buying that pitch, however. Energy market experts at Citi recently explained how they think most parts of the developing world will choose a more diversified mix of generation to bring power to those without it. It has become clear that deep poverty in India, a major coal-consuming nation, makes it very difficult to support expensive coal investments. India’s national plan to support a massive buildout of coal-fired plants has all but crumpled and the administration of the new president, Narendra Modi, is looking for broader alternatives.

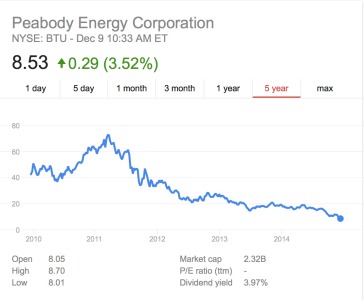

Investment analysts were most recently taken aback by Peabody when it offered a bizarre spin on the U.S.-China climate pact announced in November. The company presented the deal as a pro-coal announcement, and the reaction by Wall Street was to drive Peabody stock to record lows while the press reported that CEO Gregory Boyce was seen increasingly as not just a climate-change denier but a man unable to see the energy-market transition taking place right in front of him.

The industry-insider blow to Peabody came from Bob Murray, a fellow rock-ribbed CEO and the head of Murray Energy, who said this fall at a conference sponsored by Platts that those who cannot or will not acknowledge the changes taking place are simply fooling themselves. Murray also dismissed coal-industry rhetoric on the global energy transition as public-relations garbage produced to placate naive investors.

One might argue that Peabody is waging a last-company-standing strategy in which it hopes to pounce—and prosper—once the competition is eliminated through a long, grinding process of bankruptcies, layoffs, and consolidations. What’s happening is that energy investment is becoming more diversified across the board, criticism of coal where it is still in heavy use is growing, and where it is in little use it is seen as the least-desirable option.

Last we looked, the stock market wanted no part of Peabody’s strategy, whatever it is. Peabody is just above $8 a share, down 89 percent from its peak in April 2011 of almost $73, wholly disconnected from the S&P 500 Index, which is up 53 percent over that same period of time. Its strongest U.S. mines, in the Powder River Basin, are weak, and 2015 is not looking so good in either the U.S. or Australia.

Last we looked, the stock market wanted no part of Peabody’s strategy, whatever it is. Peabody is just above $8 a share, down 89 percent from its peak in April 2011 of almost $73, wholly disconnected from the S&P 500 Index, which is up 53 percent over that same period of time. Its strongest U.S. mines, in the Powder River Basin, are weak, and 2015 is not looking so good in either the U.S. or Australia.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.