An Ohio Wind Farm Proves the Case for a Wise Renewable-Energy Policy

Ohio, it’s fair to say, isn’t known as a leader in the transition to renewable energy.

In fact, it attracted some well-earned infamy last year when it became the first state in the country to “freeze” a requirement that utilities purchase a certain amount of their energy from renewable sources like wind and solar. That regressive move by lawmakers signaled that Ohio’s ruling politicians don’t put much stock, or don’t want to put much stock, in the new-energy economy.

And yet, in northwest Ohio’s Van Wert County sits Blue Creek Wind Farm, a 300-megawatt set of turbines that repudiates such resistance.

Although a great deal has been said about the many jobs created by renewable energy, little has been said about its effect on electricity prices. This is partly because information about “power purchase agreements” between private parties—like energy generation facilities and their customers—is usually kept confidential, which serves to keep the public in the dark about which kind of energy costs how much. But because several public entities are customers of Blue Creek, data on the price of power from the plant is available, and it tells a story worth sharing.

Spanish renewable-energy giant Iberdrola started developing Blue Creek in 2009, and the wind farm began producing electricity in 2012. The company started the $600 million project at a time when virtually all development in Ohio had ground to a halt due to the Great Recession. Iberdrola was able to finance the project off of its own balance sheet and then to take advantage of a federal stimulus program created to spur investment in renewable energy (the company qualified for a $172 million federal grant after the project was completed).

Blue Creek has signed long-term purchase power agreements with three major customers: FirstEnergy, for 100 megawatts over 20 years; American Municipal Power (AMP), for 52.2 megawatts over 10 years; and The Ohio State University, for 50 megawatts over 20 years. FirstEnergy’s contract is not made public, but IEEFA has obtained information about the AMP contracts from municipalities that purchase power from AMP, and Ohio State has released details of its deal with Blue Creek Wind.

THE DATA: WIND-POWERED ENERGY SAVES MONEY

Data from AMP and Ohio State shows that wind power in Ohio is a good deal for its customers, and that its price is competitive with, and in some cases significantly cheaper than, other sources of power.

Ohio State’s levelized price—essentially an average price—for its 20-year Blue Creek deal is $54 per megawatt hour. The wind farm provides 25 percent of the power needed to run the university, which with 58,000 students and 570 buildings is among the largest in the country.

AMP’s deal with Blue Creek set a levelized cost of electricity of $45 per megawatt hours over its shorter 10 year deal. The rate started at $35 per megawatt hour, and will ratchet up gradually, by $2 per megawatt hour, each year of the agreement.

How do we know that Blue Creek’s wind-powered energy stacks up so well on price? In part because Ohio State revealed this past February that is had saved $4 million to date on its electric bills through its deal with Blue Creek. And we can see in the data that municipalities save money by getting their electricity from Blue Creek.

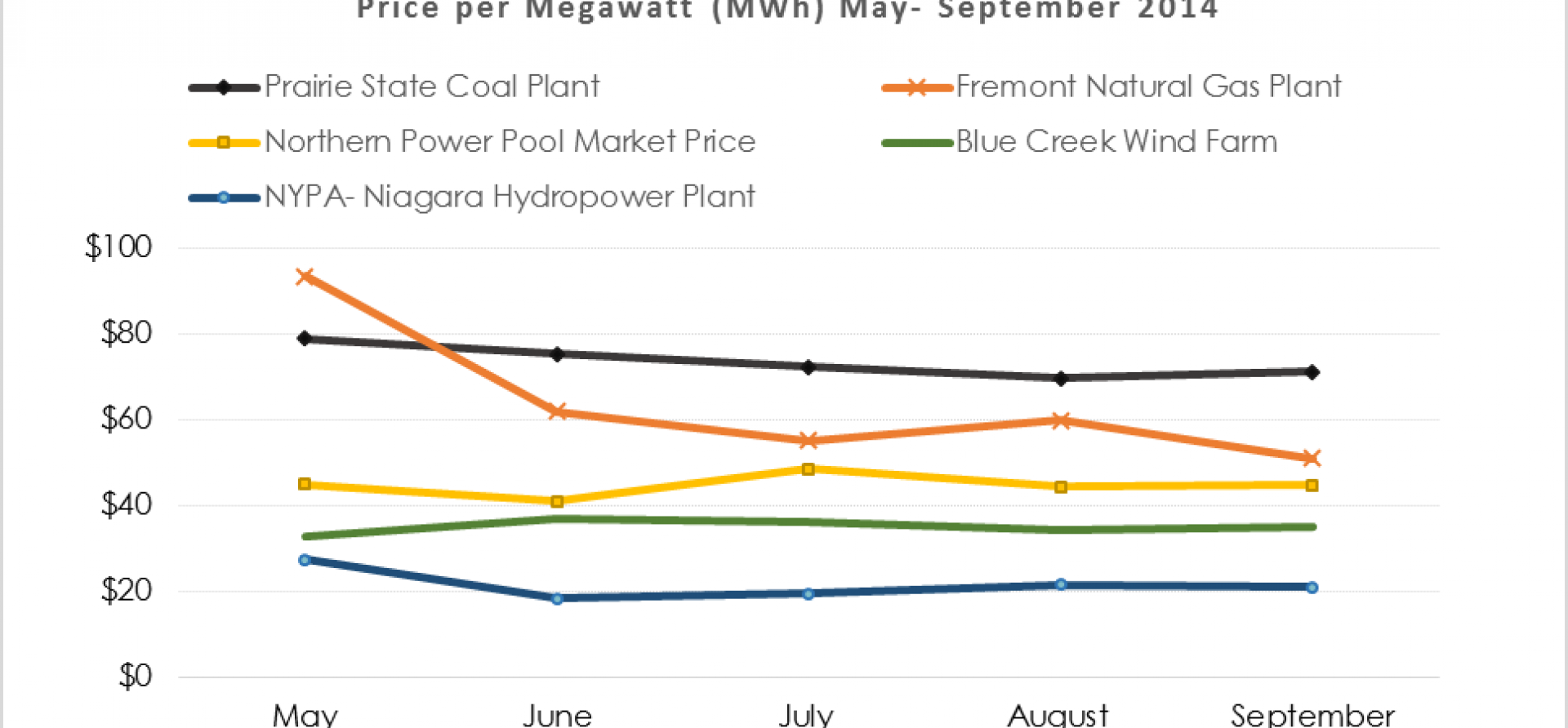

Here’s a chart, for instance, that shows the prices that Galion, Ohio, a member of AMP, paid for electricity from various sources from May to September 2014. It’s a revealing snapshot, and is compelling comparison, because Galion got its power from so many different sources. Blue Creek’s power, which cost the town about $35 per megawatt hour in 2014, was Galion’s least expensive source aside from what it paid for hydropower from Niagara Falls. Power from Blue Creek cost less than the average market price, less than electricity from AMP’s Fremont natural gas plant, and less than the power from the controversial Prairie State coal plant (which, unfortunately for Galion, provides the lion’s share of the town’s electricity).

AN INCREASINGLY IMPORTANT PART OF U.S. ENERGY MARKETS

AN INCREASINGLY IMPORTANT PART OF U.S. ENERGY MARKETS

The comparisons aren’t perfect, of course, because wind energy differs from fossil-fuel plants in that its operations are intermittent—the turbines generate energy only when the wind is blowing. So taken on its own, wind power is not a full-time substitute for fossil fuels. But wherever wind has begun to take hold, it is becoming an increasingly important share of the market. In Texas, for example, wind energy is dispatched across the electricity grid ahead of coal-fired generation whenever possible because the price is so much lower.

Wind farms do need to be counted on for a certain amount of power in order to make the deals work. This is taken into account when the projects are planned and as developers estimate “capacity factor,” which is the amount of time a plant will be operational. Blue Creek reports that it has met its average capacity factor target of 35 percent, which means it is able to dispatch the amount of electricity that customers were counting on.

Critics of wind-power deals often cite federal subsidies as proof that the projects couldn’t make it on their own. But there isn’t a form of energy in the U.S. that hasn’t received major federal subsidies. The Prairie State plant was built on the back of $1 billion in Build America Bonds, oil companies receive huge tax breaks, and the nuclear industry wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the massive federal insurance program created under the Price-Anderson Act.

It comes down to smart decision-making about where to best invest public dollars, taking into account the social, environmental, and economic benefits of any such investment. If you ask me, Blue Creek Wind Farm is a textbook case for why renewable energy deserves a public-policy tailwind.

Sandy Buchanan is IEEFA’s executive director.