West Virginia Can Reap Real Returns by Investing in Energy Efficiency

In the latest American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy state rankings, West Virginia ranks 45th, which is a shame because if there’s any state that needs energy efficiency investment it’s West Virginia, where electricity rates have soared over the past several years.

In the latest American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy state rankings, West Virginia ranks 45th, which is a shame because if there’s any state that needs energy efficiency investment it’s West Virginia, where electricity rates have soared over the past several years.

In 2008, FirstEnergy’s rates in West Virginia were just over 6.5 cents per kilowatt hour. Today they are 9.5 cents per kilowatt hour and the company reached a settlement for a 7.3 percent rate increase on top of that. American Electric Power, West Virginia’s other major electricity provider, has raised rates similarly.

West Virginia ratepayers haven’t benefitted from low natural gas prices that have driven down electricity prices in many other parts of the country because West Virginia’s utilities are so heavily dependent on coal (75 percent of AEP’s West Virginia electricity comes from coal; FirstEnergy is more than 90 percent reliant on coal).

Such dependency breeds risk, and it also bucks larger market forces. A decade ago, coal generated about half of all U.S. electricity. Today that proportion has dropped to 39 percent. The consensus among energy analysts is that it will continue to drop—to as low as 18 percent by 2030.

FORTY-TWO COAL PRODUCERS HAVE DECLARED BANKRUPTCY SINCE 2012. The largest—Arch Coal, Alpha Natural Resources and Peabody Energy—have lost more than 90 percent of their market value in the past five years. West Virginia coal production fell by almost a third from 2008 to 2014, and analysts see Appalachian coal production dropping further, by perhaps another third in the next three years. Boone County, once West Virginia’s largest coal-producing county, has lost approximately 2,700 coal mining jobs from 2011 through 2014, a decline of nearly 60 percent, and 10,000 coal-mining jobs have disappeared from the state as a whole over that same period of time.

So the West Virginia coal industry has gone bust at about the same time that the state’s natural gas industry has boomed, thanks to the Marcellus Shale. But it’s only a matter a time before that boom, too, goes bust. Commodity markets are inherently volatile.

Those recent increases in AEP’s and FirstEnergy’s electricity prices, coupled with the uncertain nature of the the state’s commodity-based economy, offer a timely reminder of the often overlooked value of investments in energy efficiency.

Energy efficiency is a resource that can meet electricity demand much like natural gas and coal can. Every unit of electricity saved through energy efficiency is one that doesn’t have to be generated. And the more electricity that can be saved through energy efficiency, the less ratepayers are subject to fluctuations in coal and natural gas prices that may drive up electricity rates. Energy efficiency provides a valuable—and inexpensive—hedge. Recent studies have put the cost of saving electricity through energy efficiency at 2.5 to 2.8 cents per kilowatt hour. The cost to generate power-plant electricity today is about 5 to 6 cents per kilowatt hour. That means that it is cheaper for a utility to invest in saving electricity through energy efficiency than to generate that power. All ratepayers benefit when utilities invest in energy efficiency because it means that the utility avoids purchasing more expensive power and, over the long term, the utility can avoid or defer building additional power plants.

Of course, utilities themselves don’t generally like to sell less of their product, nor do they necessarily want to put off major capital expenditures that they would be entitled to earn profits on. But because West Virginia hasn’t made a serious policy effort to encourage or mandate energy efficiency, its utilities—particularly FirstEnergy — are far behind other states. That’s why West Virginia ranks so poorly.

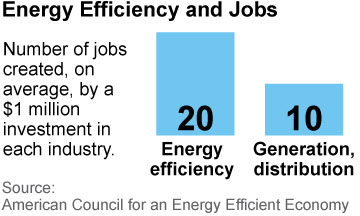

Energy efficiency also creates more jobs than energy generation. This fact is borne out in research by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy that shows how a $1 million investment in energy efficiency supports, on average, 14 to 20 jobs. A $1 million investment in conventional power generation, by comparison, supports about 10 jobs. The average wage for these energy efficiency jobs is nearly $5,000 above the national median income. It’s work that cannot be outsourced, and it’s not an industry inevitably battered by boom-and-bust cycles.

Energy efficiency isn’t a magic silver bullet and it alone will not drive West Virginia toward a more sustainable economy, but it’s a valuable and largely untapped resource that the state’s utilities should be investing in more.

Cathy Kunkel is an IEEFA energy analyst.