The Truth About Prairie State Energy Campus (Part 3): A Crippling Burden to Its Many Towns and Cities

An Ill-Conceived Power Plant Sapping the Economic Vigor of Communities Far and Wide …

Imagine, if you will, the small-business pillars of a town shutting their doors suddenly because they can’t pay their bills. Households having to choose between paying their heating bills and buying groceries. Bigger businesses, universities and hospitals being forced to cut jobs and programs so they can keep their lights on. Rating agencies raining pain on municipalities by downgrading their credit, which drives up the cost of living for residents of all stripes.

Sounds like a chapter from the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Which, of course, is what it could be—but it’s also a description of the consequences that people in towns and cities across the Midwest (and into part of Virginia) are suffering as a result of their decision to buy into the Prairie State Energy Campus, a project developed by Peabody Energy.

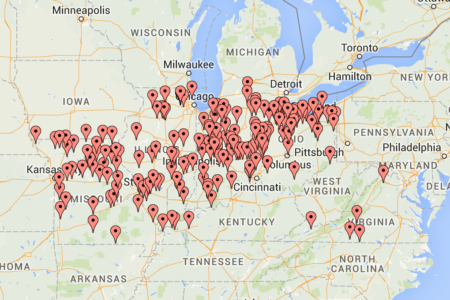

Peabody proposed the 1600-megawatt coal-fired power plant, which sits adjacent to its Lively Grove coal mine in Southern Illinois, about 10 years ago. Company executives told municipal electricity agencies that the price of electricity from the plant would be less than market prices. Local governments in more than 200 communities in eight states bought into the deal, many of them signing 30- and 50-year contracts (here’s a full state-by-state list).

Peabody proposed the 1600-megawatt coal-fired power plant, which sits adjacent to its Lively Grove coal mine in Southern Illinois, about 10 years ago. Company executives told municipal electricity agencies that the price of electricity from the plant would be less than market prices. Local governments in more than 200 communities in eight states bought into the deal, many of them signing 30- and 50-year contracts (here’s a full state-by-state list).

A few of those towns and cities were convinced by Prairie State pitchmen that the price of electricity from the plant would be so low that they could sell it on the open market and make money. It was a tantalizing proposition: Cheap electricity and a profit to boot.

But the promise never materialized—plant construction ran $1 billion over budget, and operating failures since it opened in 2012 have pushed the price of the electricity it produces through the roof. Every community that bought into Prairie State — a group that includes 2.5 million ratepayers by Prairie State’s own estimates — has had to figure out how to adjust electric rates to account for generation prices that are often twice as high as market prices. Those municipal governments that were talked into believing they could even sell some of their share of the electricity have taken an even bigger bath.

ON THE HOOK, NO MATTER HOW POORLY THE PLANT PERFORMS

Communities in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, and Virginia have been particularly hard hit because they signed “take-or-pay” contracts with their umbrella municipal electric associations, which issued some of the bonds that paid for the $4.9 billion project. These communities pledged their electric revenues to pay back the bonds, and are now on the hook to pay for the plant no matter how expensive it is or how poorly it performs. They’re also obligated to pay a portion of the share of losses from other participating cities if those municipalities default.

These many contract provisions, which made the deal so attractive to the bond market are the very provisions that cause the most hardship for consumers. In a report on Prairie State issued on March 9, Fitch Ratings concluded that the plant has favorable “long-term fundamentals” because member communities will have to pay for the cost of power regardless of how high it goes.

Here’s how some of the towns and cities that own some of the largest shares of the plant are suffering from an investment that was supposed to bring them savings:

- In Paducah, Ky., which owns the single largest municipal share of the plant (104 megawatts) even though the town’s population is barely 25,000, electricity rates have skyrocketed, and businesses have closed shop because they can’t pay for their electricity. Customers pay the highest power bills in the state, and Western Baptist Hospital estimates that its annual electric bill has soared by $800,000. A Fitch Ratings review in November 2014 said Paducah Power System, the local entity that bought into Prairie State, had only two weeks of cash on hand.

- Batavia, Ill., the second-largest municipal stakeholder in Prairie State (55 megawatts) has had to raise its electric rates and increase its sales tax to keep up. The town required a $7.5 million subsidy from the state to protect its largest electric users, and citizens and small businesses filed a class action lawsuit last August against the firms that told the city it should join the deal. The city has also formally requested Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan to conduct a formal investigation into how this debacle occurred.

- Columbia, Mo., the third-largest owner (50 megawatts) relies—unlike Paducah and Batavia—on Prairie State for only a portion of its electricity but recently has had to raise rates nonetheless, and residents are urging the City Council to hold hearings on the economic consequences of its long-term tie to the plant.

- Danville, Va., which has a 49.76-megawatt share, is having such severe problems with its electric rates that it is trying to sell its municipal power agency to a private company. Complicating this is the fact that Danville and nearby Martinsville pay higher transmission and “congestion” costs for Prairie State power than many other member communities because they are located so far from the plant.

- Bowling Green and Hamilton, Ohio, each have a 35-megawatt stake in the plant and both are suffering because of it. Bowling Green has raised its electric rates by 25 percent over the next five years to cover the cost of Prairie State’s electricity (and American Municipal Power’s very expensive hydroelectric plants). The situation has placed tremendous strain on Bowling Green State University, the town’s biggest electricity customer, and Fitch has cited Hamilton as being under “financial stress and considering rate hikes.”

- Cleveland, Ohio, (24.8 megawatts), Piqua, Ohio, (19.9 megawatts) and Celina, Ohio (14.9 megawatts) are all noted for being at risk because of their exposure to Prairie State. Cleveland in particular is in jeopardy because Cleveland Public Power is the only municipal utility in the state that competes house-to-house with private utilities. If the utility’s rates become higher than its major competitor, FirstEnergy, it will most likely plunge into a financial spiral. Standard and Poor’s downgraded Cleveland Public Power’s bond ratings to “negative” last year, and an independent consultant hired by the city said its high-priced fixed contracts for electricity must be remedied.

A ‘TOXIC ASSET’ BEYOND THE MEANS OF ANY COMMUNITY

This list—damning though it is—doesn’t include the many other towns and cities—small communities, especially—that have been economically hammered by Prairie State, among them Hermann, Mo., which just last week filed a lawsuit that may serve as a model for others to follow.

There’s also the bit of history surrounding the town of Marceline, Mo., which set a precedent in 2014 by negotiating an exit from its deal with Prairie State, calling the plant a “toxic asset” it couldn’t afford.

In fact, no municipal member of Prairie State Energy Campus can afford it. To borrow a phrase from H. Ross Perot—that giant sucking sound you hear is the sound of Peabody Energy, investment bankers, bond brokers, accountants, lawyers and bondholders siphoning money from hundreds of thousands of ratepayers’ pockets.

Sandy Buchanan is IEEFA’s executive director.

Tomorrow: A Workout Is Not Out of the Question

Related posts:

The Truth About Prairie State Energy Campus (Part 1): Failing, Year by Year

(Part 2): Its Coal Isn’t Cheap

(Part 4): There Are Ways Out of This Bad Deal