Towards a rooftop solar transition in Bangladesh

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

Upscaling the rooftop solar sector requires risk-mitigation instruments, business models for utilities, waiver of import duties on solar accessories and easing the letter of credit opening process.

While the economic benefits of rooftop solar are clear, its slow progress shows the sector is held back by a lack of awareness, low confidence, perceived risks, high import duties, and tight fiscal conditions.

New rooftop solar capacity of 2,000MW could save the Bangladesh Power Development Board between Tk52.3billion (US$476 million) and Tk110.32 billion (US$1 billion) a year.

Awareness raising, capacity development of stakeholders and quality assurance of accessories will help build trust in rooftop solar.

Executive Summary

The limited rooftop solar capacity of 160.63 megawatts (MW), installed under net-metered and non-net-metered systems until 10 October 2023 in Bangladesh, has proved grossly inadequate.[1],[2] As frequent load-shedding and energy supply disruption stifle industrial production and economic activity, adding 2,000MW of rooftop solar can provide some relief to the country.

A similar capacity addition in rooftop solar can also help the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB). BPDB has a high revenue deficit each year owing to expensive power generation and purchases from furnace oil- and diesel-fired plants. We estimate that adding 2,000MW of rooftop solar capacity could help the BPDB save between Tk52.3 billion (US$476 million) and Tk110.32 billion (US$1 billion) a year by reducing generation and purchase of costly power.

There have been some encouraging signs recently. The capacity addition of 42.04MW – net-metered and non-net-metered rooftop solar systems combined – in 2023 was the highest in a year since the first rooftop system was installed in 2012.[3] The government introduced regulation changes in August 2023, making rooftop solar a prerequisite for grid connection for different establishments. It also floated an international tender for deploying rooftop solar in jute mills. Some universities are prioritising rooftop solar.

Rooftop solar also appears to make more financial sense for industrial and commercial consumers. The levelised cost of energy (LCOE) from rooftop solar stands at Bangladeshi Taka (Tk) 5/kilowatt hour (kWh) (US$0.046/kWh) against the electricity tariffs of Tk9.9/kWh (US$0.09/kWh) and Tk10.55 (US$0.096/kWh) for industrial and commercial buildings, respectively.[4] These tariffs are not only attractive to industrial and commercial buildings to install rooftop solar systems but also better than the rates that triggered 9 gigawatts (GW) of such capacity addition in Vietnam in 2020. Yet, the sector’s slow progress shows industry and building owners’ interest in taking up rooftop solar is scattershot.

Barriers to the Rooftop Solar Sector

Building on available information and interviews with stakeholders from seven major groups, this study identifies barriers to the sector’s progress. These barriers include the awareness level of consumers, the presence of high import duties on equipment, the cap on rooftop solar system capacity, financiers’ risk averseness, service providers’ risks, lack of business models for utilities, fiscal conditions, capacity level of major stakeholders.

People are gravitating towards rooftop solar, albeit slowly, due to a lack of awareness and trust in its benefits. Low-quality rooftop solar installations while obtaining new grid connections in the past negatively affected the confidence of building owners. Most stakeholders do not see the upfront cost of rooftop solar as a significant obstacle since the system cost continues to fall. However, high import duties disproportionately affect rooftop solar as opposed to utility-scale solar projects. Such duties make rooftop solar costly in Bangladesh. The cap on installation capacity of up to 70% of the sanctioned load prevents some industries or commercial buildings from enjoying more benefits.

Rooftop solar is disproportionately affected by high import duties as opposed to utility-scale solar projects.

The available financing vehicles for rooftop solar are lucrative but not without problems. Most financial institutions, excluding Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL), do not prioritise rooftop solar projects due to small financing opportunities. Stakeholders shared that most financial institutions are not accustomed to assessing the feasibility of rooftop solar projects. Investors are also reluctant to spend on high-quality feasibility studies. IDCOL has substantial experience assessing rooftop solar projects and a dedicated financing facility for them. Still, it can only meet a small fraction of the overall demand for finance in the foreseeable future. The green refinancing scheme of the Bangladesh Bank is limited and has a lengthy process.

All financial institutions demand high collateral, such as land, bank and personal guarantees, to minimise their risk exposure, which affects project implementation. Likewise, they are less willing to extend loans to Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) companies for projects under the operational expenditure (OPEX) model, which can swiftly increase rooftop solar uptake.[5] EPC companies foresee the risks of payment delay/default from building owners (offtakers’).

While utilities can accelerate rooftop solar deployment, without any incentive, they do not have a motivation to front-load efforts.

The Tk depreciated by 28.8% against the US$ between December 2021 and September 2023. The depletion of foreign currency reserves sparked government intervention to restrict imports of luxury goods. However, the initiative ended up being counterproductive for rooftop solar. Without a tag of essential goods, there were delays in the opening of the letter of credit (LC) for the import of rooftop solar accessories, affecting project implementation.

Notably, working in tandem with policymakers and relevant stakeholders, associations create an enabling environment for clean energy. However, the Bangladesh Solar and Renewable Energy Association (BSREA) has its own operational challenges, which limit its effectiveness in the sector.

An analysis of different stakeholders of the rooftop solar sector demonstrates that only the nodal agency of the clean energy sector, the Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA) and EPC companies exhibit more than average capacity to spearhead a change from the status quo. The rest have less than average capacity.

Key Levers to Upscale Rooftop Solar in Bangladesh

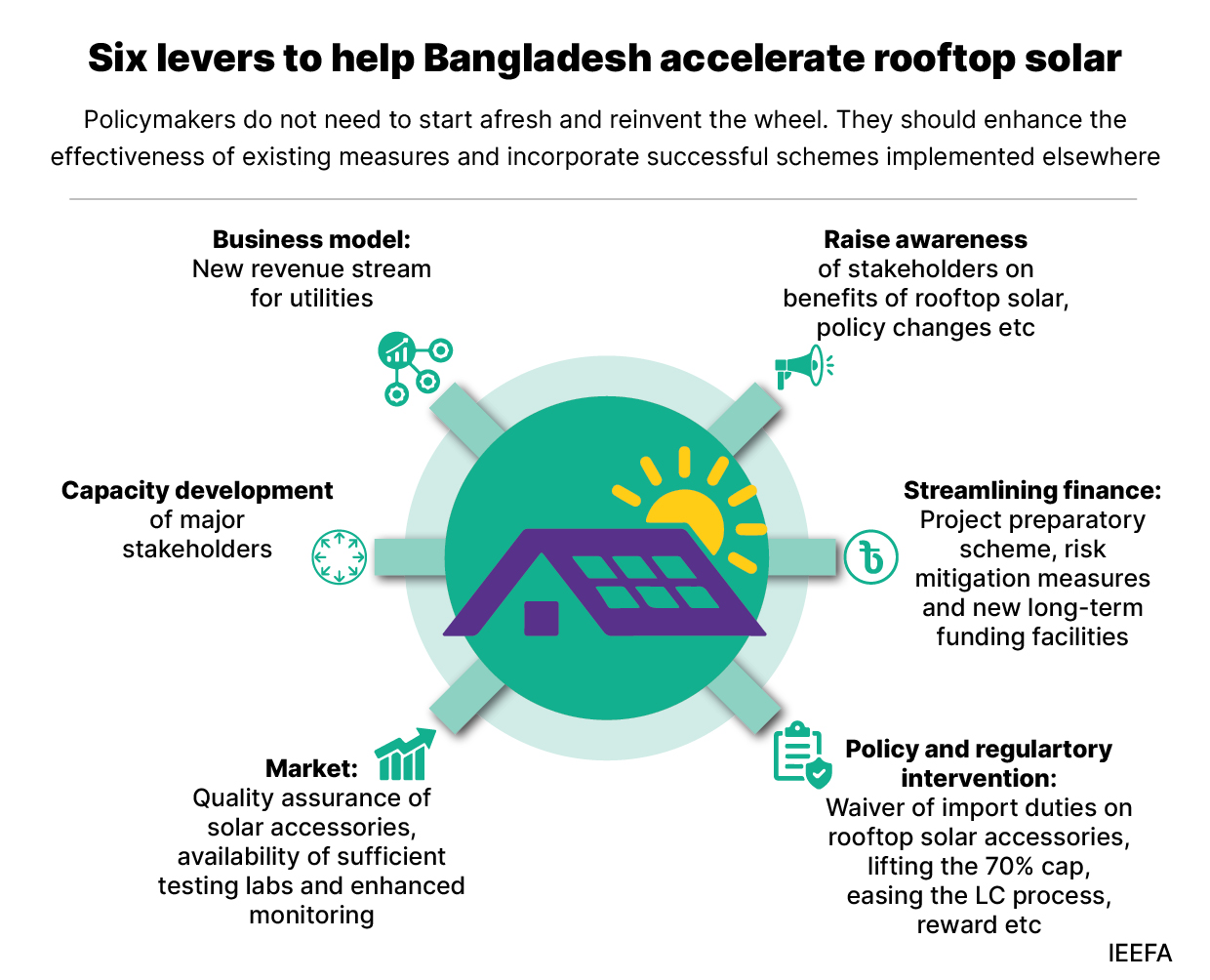

The study recommends six key levers to upscale the rooftop solar sector quickly and effectively. These are raising awareness, streamlining finance, policy and regulatory intervention, quality assurance, business models for utilities and capacity development of key stakeholders (Figure 1).

While investors want to quickly assimilate information on interest rates, net metering guidelines and policy changes, there is information asymmetry within the sector. Moreover, the government recently changed net-metered rooftop solar targets for new grid connections and interest rates of the low-cost refinancing scheme. Therefore, raising awareness of the rooftop solar segment is indispensable. The solar helpdesk, hosted by SREDA, shares information on request, but stakeholders feel a performance assessment of the desk is essential to upgrade services based on need and relevance.

A credit risk guarantee scheme can minimise the perceived risks of financial institutions and smoothen fund flows to projects under the capital expenditure (CAPEX) and OPEX model, thereby reducing the demand for high collateral. A first-loss guarantee can address EPC companies’ challenges linked to repayment from offtakers. A project preparatory scheme will ensure high-quality feasibility studies of rooftop solar projects, boosting the confidence of financial institutions. While Bangladesh Bank’s green refinancing scheme is the least-cost financing vehicle, all eligible rooftop solar projects will not receive the refinance due to its limited funds of Tk4 billion (US$36.4 million) and the competition with 69 other environment-friendly projects. Stakeholders further claim that the refinancing process is time-consuming. Therefore, Bangladesh Bank may pre-approve financing for rooftop solar based on an assessment at the initial stage to eliminate any uncertainty about availing of the low-cost scheme.

IDCOL’s financing scheme is also appealing, but increasing rooftop solar use in the country will require additional financing. This will make it necessary for local financial institutions to explore sources, including multilateral agencies, international climate finance and the local bond market, in the foreseeable future.

Our study substantiates the need for a waiver on prevailing import duties on solar panels and four accessories, ranging from 11.2% to 58.6%, at least for a limited period. Since utility-scale solar projects enjoy a complete duty waiver, the government should treat rooftop solar equally. We recommend fixing the rooftop solar installation capacity to 100% of the sanctioned load to make it more attractive.

As rooftop solar accessories are usually imported, the Bangladesh Bank and the National Board of Revenue (NBR) should declare rooftop solar a top priority and ease its LC opening process.

For a rapid expansion, the Bangladesh Bank may give financial institutions an annual disbursement target on renewable energy, including rooftop solar.

Most stakeholders note that rooftop solar already has a compelling economic case and do not suggest providing financial incentives as the country’s fiscal burdens continue to mount amid depreciating foreign currency. However, they feel that along with a duty waiver of rooftop solar accessories, awards and recognition could motivate industry and building owners to pursue rooftop solar. The government may recognise the contribution of the best-performing rooftop solar projects in the National Environment Award ceremony or introduce a National Clean Energy Award.

Utilities specialising in power generation, transmission and distribution could spur rooftop solar expansion in the country. But they need a revenue stream for their intrinsic motivation. Both the utility- and third-party-owned business models can serve this purpose.

Moreover, unless the quality of accessories is maintained, rooftop solar expansion will not really be hitting the target. Setting up enough testing labs and increasing market monitoring by the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institute (BSTI) could address quality concerns around accessories. Stakeholders said that SREDA can include a consumer feedback mechanism for EPC companies and solar equipment suppliers to ensure quality project implementation and initiate certification for service providers.

SREDA should design and conduct targeted capacity development and awareness programmes, as well as exposure visits to successful projects for stakeholders. However, SREDA should increase its workforce to fulfil its responsibilities, from policy formulation to sector coordination and capacity development. Likewise, utilities require additional staff to manage the increasing volume of applications for net-metered rooftop solar and adopt new business models for upscaling.

Bangladesh does not need to start afresh and reinvent the wheel. It should enhance the effectiveness of existing measures, such as raising awareness and capacity building, making policy conducive by addressing barriers and adopting a credit risk guarantee scheme and successful business models for utilities implemented elsewhere.

The country must tap the low-hanging fruit of rooftop solar to stave off the energy sector challenges and reduce colossal imports of fossil fuels. The delay in steering the sector in the right direction could result in a missed opportunity. Finally, this evidence-based assessment of the rooftop solar sector would provide a solid empirical base for future studies.

Footnotes:

[1] Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority (SREDA). Statistics of Installed Net Metering System. 31 October 2023.

[2] SREDA. Rooftop Solar Except Net Metering. 31 October 2023.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Industries and commercial buildings having sanctioned loads from 50 kilowatts (KW) to 5MW enjoy the mentioned flat tariff rates.

[5] EPC companies invest in OPEX model as opposed to the capital expenditure (CAPEX) model where building owners such as industries invest.