Shell’s rationale for rapid LNG demand growth looks increasingly fragile, despite higher forecasts

Key Findings

Shell released its annual Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Outlook, laying out the bullish case for LNG market growth over the next 15 years. The company’s underlying rationale for rapid LNG demand increases masks fundamental flaws in its LNG thesis and financial risks for investors.

Shell assumes LNG will provide the largest share of global natural gas demand growth through 2040, disregarding that in the last 20 years, most incremental demand has been met by gas that is domestically produced, not traded.

Shell implies that tight markets could maintain upward pressure on global prices, dismissing that high prices hinder LNG’s ability to compete with other fuels, like coal and renewables, thus limiting LNG demand.

Shell’s newest outlook differs from previous years by downplaying LNG’s role in the power sector and no longer emphasizing claims that LNG can displace coal in Asia. Instead, it highlights LNG infrastructure investments and potential LNG use for transport in India and China.

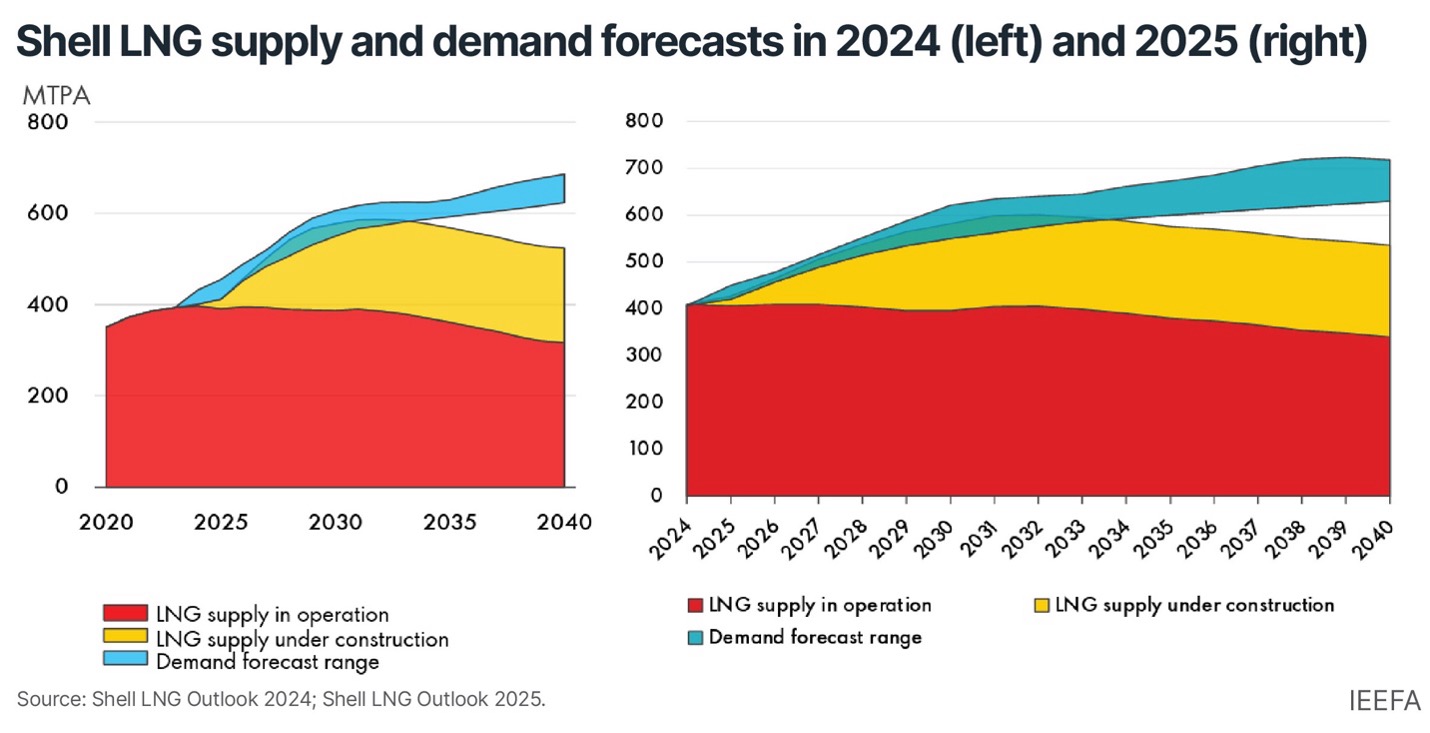

Last month, UK oil and gas major Shell released its annual Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Outlook, laying out the bullish case for LNG market growth over the next 15 years. This year, the company increased its demand expectations to between 630 and 718 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) by 2040, 1-5% higher than last year’s projection.

However, the latest outlook is heavy on investor optimism but light on details. It provides less justification for bullish demand scenarios than in previous years, and key demand drivers that featured prominently in 2024 were downplayed or omitted entirely.

As a result, Shell’s underlying rationale for rapid LNG demand growth appears increasingly fragile. While higher projections justify the company’s sizable LNG portfolio, they mask fundamental flaws in the LNG growth thesis and financial risks for investors.

Fundamental flaws in Shell’s LNG thesis

Shell forecasts that LNG trade will grow rapidly for the remainder of the decade, followed by slower growth in the 2030s. Last year, the company anticipated global demand peaking in the 2040s, but its latest high-demand scenario now suggests a peak in 2039.

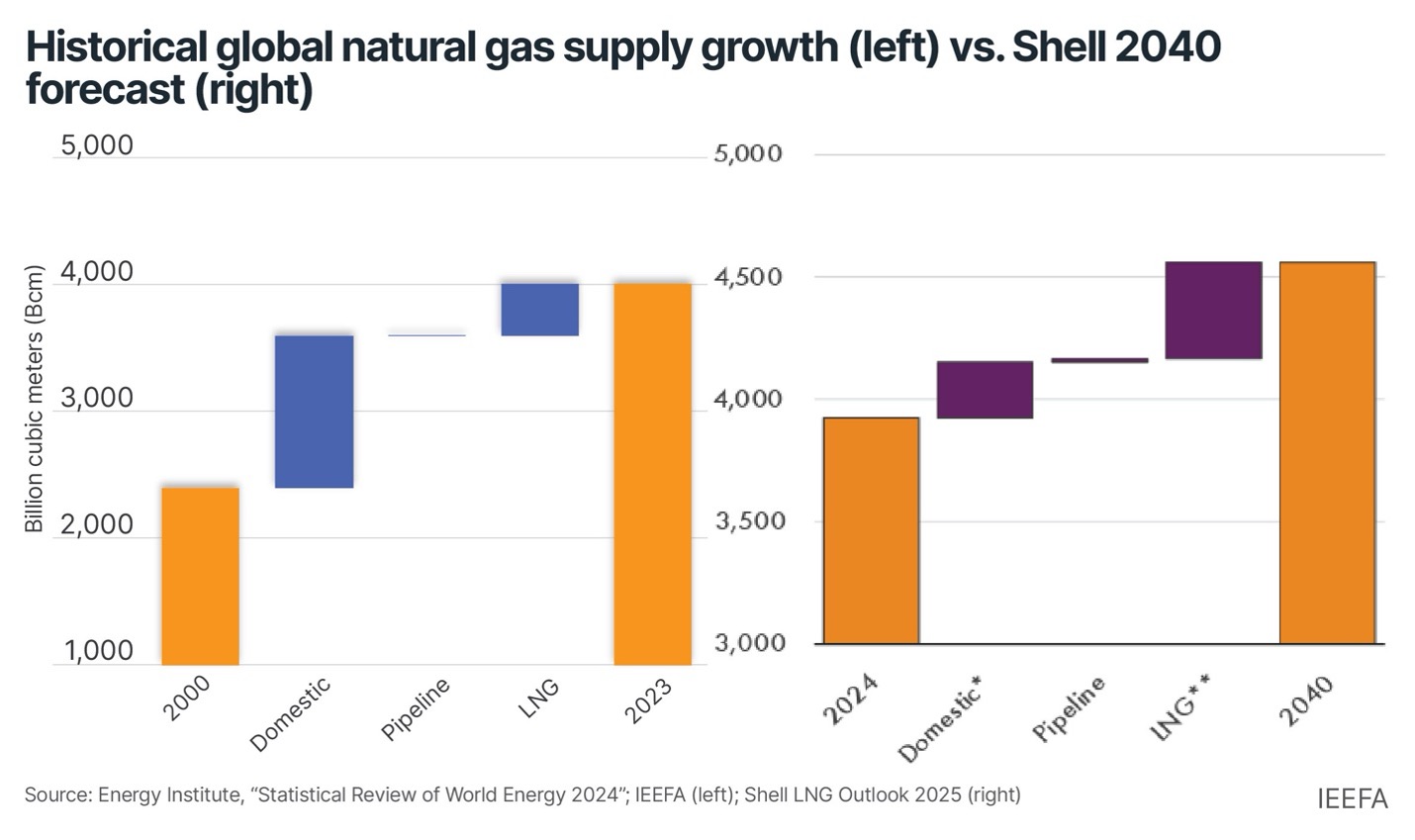

Expectations for rapid LNG demand growth face several fundamental pitfalls. First, the company believes LNG will provide the largest share of global natural gas demand growth through 2040. However, over the last 20 years, the majority of incremental demand has been met by gas that is domestically produced, not traded.

With the exception of China, natural gas consumption has grown mainly in countries that produce enough gas to either be self-sufficient or net exporters, like the U.S. By contrast, gas demand has tended to fall in markets that require large import volumes, like Europe and Japan. By banking on LNG as the largest growth driver, Shell expects the natural gas trade to break out of a trend that has existed for over two decades.

A second issue is that under Shell’s high-growth scenarios, demand exceeds supply through 2040, implying that tight markets could maintain upward pressure on global prices. This is paradoxical as high prices hinder LNG’s ability to compete with other fuels, like coal and renewables, thus limiting LNG demand.

While lower prices will be necessary to stimulate growth, particularly in emerging economies, they would also result in smaller returns for LNG companies and their shareholders - a point conspicuously overlooked.

Finally, Shell’s newest outlook departs from previous arguments about the key drivers of incremental LNG demand. It downplays LNG’s role in the power sector and no longer emphasizes claims that LNG can displace coal in Asia.

Instead, Shell’s outlook now argues that data centers and artificial intelligence (AI) will drive long-term LNG demand without providing any evidence. Ongoing innovations have demonstrated how energy-efficient AI models can undermine the need for gas investments. Although Shell attempts to capture recent market hype, the impact of AI on LNG demand remains highly uncertain.

India and China take center stage, while Southeast Asia takes a backseat

Shell’s latest outlook also pivots away from LNG growth in Southeast Asia, instead highlighting LNG infrastructure investments and potential LNG use for transport in India and China.

However, China’s domestic gas production and pipeline imports are growing faster than LNG due to lower costs. Domestic production accounted for almost half of the country’s natural gas demand growth last year, while pipeline flows from Russia have reached full capacity. China’s LNG imports increased in 2024 but failed to surpass 2021 levels, and LNG purchases fell to five-year lows in February 2025. Recent trade tensions with the U.S. only validate China’s strategy to prioritize other gas supplies.

Shell suggests that China and India will see higher LNG demand for trucking. China’s LNG truck fleet has nearly tripled since 2019, but government data indicates that the country liquefies enough of its own natural gas to meet trucking demand without imported LNG. Wood Mackenzie recently concluded that China’s “surge in LNG trucks will not last” due to the growth of battery electric trucks. India is significantly farther behind in adopting LNG trucks, and scalability remains a persistent challenge.

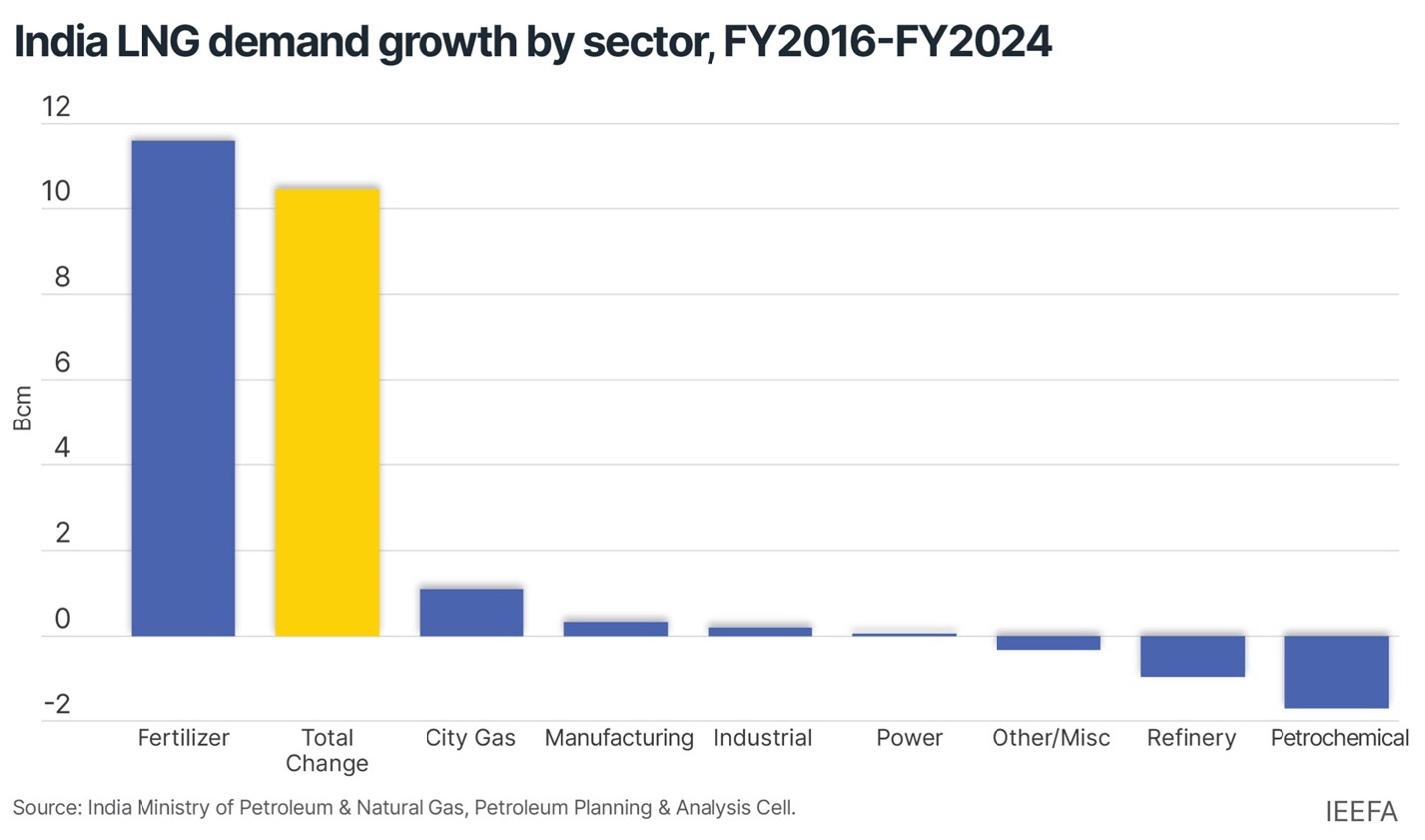

The affordability of LNG also remains highly questionable in India. Between 2016 and 2024, India’s LNG consumption remained relatively flat in nearly all sectors except for fertilizer, which relies on large government subsidies to maintain low consumer prices. LNG demand has remained limited in sectors that do not receive fiscal support. For example, global LNG prices would have to fall by half to compete in power generation, where gas provides less than 2% of the electricity mix.

Why did Shell omit details about Southeast Asia in its latest outlook? One potential reason is that the downside risks to the region’s demand growth became even more apparent in 2024.

Vietnam provides a clear example. The country’s latest Power Development Plan initially targeted 22 gigawatts (GW) of LNG-fired power capacity by 2030, but a recent draft revision lowered the target to 18GW due to slow progress. To date, only one LNG plant with 1.6GW of capacity has secured a power purchase agreement. Very few other projects may be operational before 2030. Vietnam’s wind and solar generation now exceeds gas-fired power generation, which has fallen 45% since 2015.

LNG demand in emerging Asian markets has vastly underwhelmed historical growth forecasts. For example, in 2019, some expected combined imports from Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Bangladesh, and Pakistan to reach 56MTPA in 2025 and 83MTPA by 2030. In 2024, imports to those countries were just 27MTPA.

Grasping at straws

All told, the volume of LNG traded in 2024 grew by its lowest level since 2012, according to Kpler data. While Shell’s latest LNG Outlook increased overall demand expectations by 2040, the underlying drivers for growth appear flimsy. Rather than acknowledge fundamental issues or downside risks to its core LNG thesis, Shell seems to be selectively grasping at straws to validate its long-term LNG gamble.