Private equity in PJM: New risks for limited partners, private capital

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

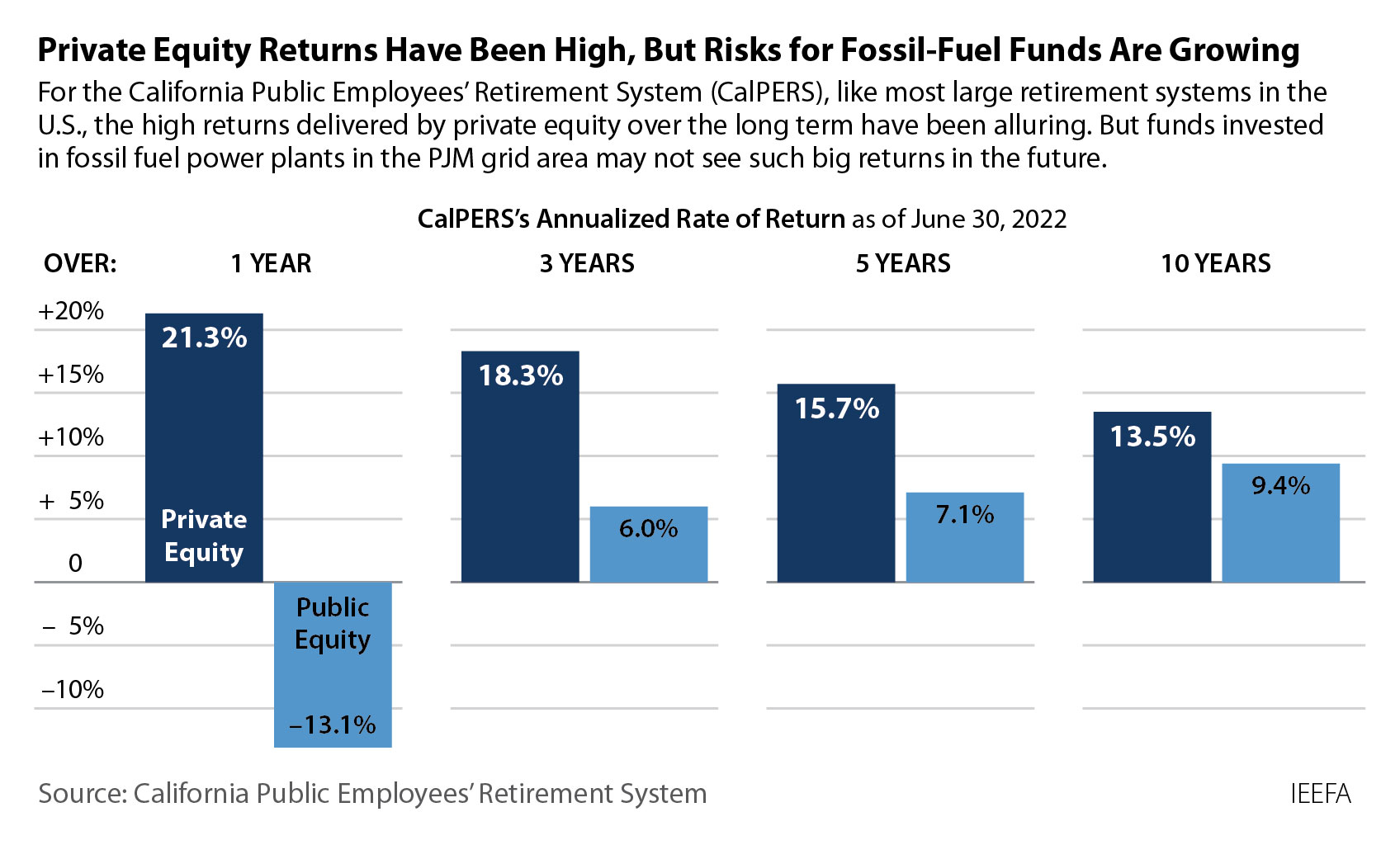

The changing regional power environment is likely to shift the outlook for pension funds and other institutional investors with holdings in private equity firms by lowering annual returns, raising investment risks, or both.

Beyond financial risks, investors face mounting reputational risks from their gas and coal investments as concerns increase about climate change and the negative impact of fossil fuel emissions.

The next few years could see additional performance problems at many of these infrastructure and PJM-focused funds, potentially lowering returns for investors.

It is a new, much riskier situation for private equity firms with holdings in the nation’s largest power market, and those risks are now trickling down to investors.

Executive Summary

Private capital, particularly difficult-to-track private equity (PE) investment, has reshaped the PJM power market in the past decade. PJM data shows that 35,515 megawatts (MW) of combined cycle gas-fired capacity have been built in the 13-state regional system since 2011, reflecting the impact of the fracking revolution that brought plentiful, low-cost gas supplies to the market. PE and other private sources developed more than 80% of the total—28,815MW.

This gas-driven growth, coupled with significant PE investment in the region’s coal-fired power plants, has transformed the ranks of PJM’s largest generating companies. As recently as 2017, the five largest capacity owners were all regulated and/or publicly traded: American Electric Power, Dominion Energy (the parent of Virginia Power), Exelon (the parent of Commonwealth Edison), FirstEnergy and NRG Energy. Today, three of the largest generators are private firms—ArcLight with 14,230MW of operating capacity; LS Power, with 10,803MW; and Talen (now controlled by Nuveen/TIAA and Rubric Capital), with 10,370MW. Beyond these three majors, there are a host of private and PE firms that own between 1,000MW and 5,000MW of capacity. Together, private capital now owns roughly 60% of the fossil fuel-fired generation capacity in PJM.

Ownership status is important. Utilities are overseen by state regulators who have a vested interest in keeping costs for ratepayers in check; merchant power companies owned by private capital are largely free from that oversight. Utilities, as well as publicly traded independent power producers, are also required to file regular financial reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission; private capital, by and large, is not. These differences largely shield private firms from regulatory and financial oversight and public pressure.

In a three-part report, IEEFA is examining the increasing risk environment in PJM, the nation’s largest power market. This second report focuses on the limited partners (LPs)—the pension and retirement funds that have poured money into the PE sector in the past decade, and generally have been well rewarded for their investments. But the changing regional power environment is likely to shift the outlook for outside investors by lowering annual returns, raising investment risks, or both. This report pays particular attention to the fallout from bankruptcy filings, in which funds and other private entities end up owning assets they may not want. For example, Nuveen/TIAA now finds itself in that situation for the second time in three years, following the recent bankruptcy restructuring of Talen Energy, and the earlier bankruptcy restructuring of FirstEnergy Solutions, which became Energy Harbor.

In the first of our reports, we examined the rising financial risks facing PE and other private firms. These risks include the recent substantial drop in capacity prices, the financial fallout from the 2022 winter storm and ongoing market reform efforts by the system operator.

In the third and final report, we will examine the risks posed by PE’s relative immunity from oversight and public pressure. This is a particularly serious threat for the places where the plants operate, since PE generators can decide on short notice to close a facility if the economics no longer work, leaving unprepared communities facing significant economic dislocations from job and tax losses. Similarly, PE’s lack of public accountability creates the very real possibility that efforts to curb regional carbon dioxide emissions will become more difficult in the years ahead. PE firms and other private capital now account for more than 50% of the PJM region’s annual power-related carbon dioxide (CO2) releases, but the sector’s lack of transparency shields it from the types of public pressure that have helped convince publicly traded electric utilities to move (however haltingly) toward decarbonization efforts.