Peak profits are a memo to miners to swap out coal for critical minerals

Download PDF

Key Findings

Current high thermal coal prices may last for a while, driving mining company cashflows, but the long-term outlook for thermal coal exports is darkening.

Some progressive mining companies have moved to investing in future-facing commodities to ensure their businesses’ long-term viability.

Australia risks losing out if industry and governments do not accelerate investments in these future-facing industries.

Although the global energy crisis may extend the good times for Australian thermal coal miners, the prevailing high prices will eventually fall.

The question is, is this an opportunity for coal miners to diversify rather than focus on large shareholder returns?

Australia’s major thermal coal producers are sitting on a cash pile after the recently announced record profits due to the global energy crisis.

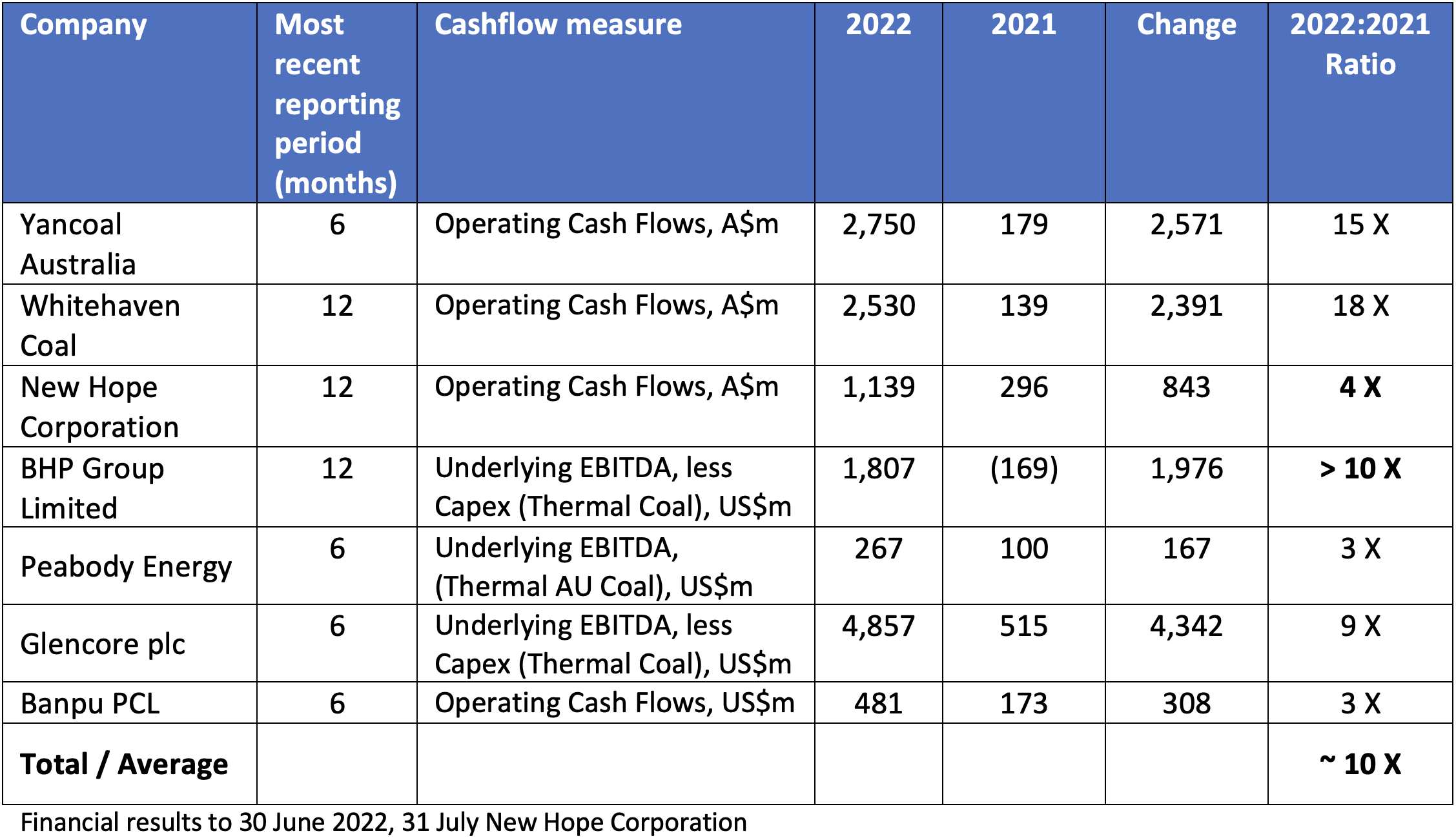

We estimate the collective free cashflow generation from seven of Australia’s major thermal coal operations to be approximately 10 times greater in 2022 than 2021 – at the current record rate of export prices of the fuel.

Estimate of reported cashflow generation for Australia’s major thermal coal exporters

Coal miners are clearing debt and increasing shareholder returns through these high cashflows. Whitehaven Coal had already pledged almost $1 billion to shareholder returns this year but will now seek shareholders‘ approval for another round of share buybacks in October and share buybacks could top $2 billion in the year ahead.

However, the high thermal coal prices are a double-edged sword for miners. At this stage of the energy transition, high prices will destroy long-term demand for coal even faster.

A recent IEEFA report found that the long-term outlook for Australian thermal coal exports faces the risk of a decline. This is because the largest global coal consumers are increasing their self-sufficiency and accelerating clean energy technologies to reduce exposure to expensive fossil fuels and meet decarbonisation goals.

While some Australian producers remain pure-play coal companies, others, such as BHP, South32 and Anglo American, are consciously moving into future-facing commodities like copper and nickel to ensure their businesses’ long-term viability.

Meanwhile, pure-play coal miners remain focused on shareholder returns with some new coal investments. This is despite the opportunities in new energy minerals and metals in Australia.

The Federal Government’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources projects that Australia’s lithium exports will double to $9.4 billion by 2023-24.

According to the CSIRO’s July 2022 Megatrends report, the 2030 outlook for Australian commodities suggests that demand for steel, zinc, copper, aluminium, rare earth elements, lithium, uranium and nickel will keep rising.

The report adds that increasing population and income levels, urbanisation and consumption of electronics, and the transition to zero-emissions technologies will drive demand.

Over the past year, the state and federal governments have each launched Critical Minerals Strategies.

In November 2021, the NSW government released its Critical Minerals and High-Tech Metals strategy, while SA launched its Thinking Critical in South Australia initiative.

In March 2022, the federal government launched the 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy. In June 2022, the WA Government released a prospectus promoting investment opportunities in the state’s growing battery and critical minerals industries.

The Queensland government launched the Resources Industry Development Plan and finally, in September 2022, the Victorian government announced it is backing a critical minerals start-up.

A new IEA Energy Sector roadmap for Indonesia – the world’s largest thermal coal exporter – provides further insight.

According to the IEA, around 85% of Indonesia’s coal exports are to countries with net-zero emissions targets, which casts doubt over long-term prospects.

However, Indonesia is the world’s biggest nickel exporter and the second-largest tin producer, both of which are key metals for clean energy technology.

The IEA finds that Indonesia is attracting investment for these minerals, with US$30 billion invested in the nickel value chain in the last few years, mainly by Chinese companies. It adds that the transition offers “large opportunities for Indonesia to diversify its economy”.

A recent IEEFA report found a combined $US6.8 billion cash balance from Indonesian coal companies allowed them to diversify away from coal.

Some South African coal miners are already eyeing such diversification. Exxaro is looking at shifting into copper, manganese, bauxite and green hydrogen. Seriti Resources is also diversifying, although some miners in South Africa remain focused on coal.

Australian asset manager Clime recently stated that typically companies invest a part of free cashflow in future growth, but coal miners have no choice but to distribute profits to shareholders as they have nowhere else to invest.

Clime’s Chairman John Abernethy stated, “Normally in a long-term thinking company, in a long-term commodity, they will take part of the free cash flow and invest it to get future growth, but in coal, there is no future.”

However, some may think differently with alternative mining opportunities and growing coal mine rehabilitation costs to fund going forward.

If industry and governments do not accelerate investments in these future-facing industries, Australia risks losing out on the growing demand for new energy commodities. Whether industry and investors cease their single-minded pursuit of harvesting shareholder returns remains to be seen.

This article first appeared in Renew Economy.