Peabody Comes Clean. But Not Very.

After a long investigation by the New York State attorney general, Peabody Energy says it’s going to do a better job of how it discloses the many financial risks it faces around climate change.

After a long investigation by the New York State attorney general, Peabody Energy says it’s going to do a better job of how it discloses the many financial risks it faces around climate change.

From the New York Times this morning:

“The N.Y.A.G. concludes that Peabody’s disclosures denied its ability to reasonably predict the future impact of any climate change regulation on its business,” the settlement says, “while the company and its consultants projected severe impacts from certain potential regulations that would materially affect Peabody.”

In its next filing to the S.E.C., Peabody agreed to a fuller disclosure of the risks as well as projections by the International Energy Agency of lower global coal demand in the future, should stronger regulatory action be taken around the world. The risks noted will include unfavorable lending trends for financing coal-fueled power plants overseas as well as divestment campaigns targeting the investment community, “which could significantly affect demand for our products or our securities.”

It’s always good (for investors especially) when companies admit past failings. This cleanup of Peabody’s Securities and Exchange filings means that previous filings can be seen now as delinquent. That’s unfortunate of course because investors, policymakers and regulators depend on such filings for accurate reflections of the health of a company.

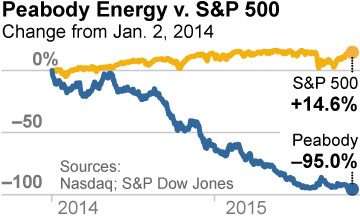

Revelations from this agreement add to Peabody’s considerable record of other misstatements, including ones like this on energy poverty, as well as a host of forward-looking financial statements that no one believes anymore. That particular distrust is evident in the performance of the company, which has said time and again that everything’s all right even as it has lost more than 90 percent of its value just since early 2014.

Peabody’s disclosures are chronically misleading, at best, and we’d rank among the starkest examples of its lack of transparency its so-called transparency around the Prairie State Energy Campus in Illinois. That poorly performing power project, spearheaded in 2012 by Peabody Energy, has saddled more than 200 Midwest communities with electricity costs that are unaffordable and that stand to hinder their economies for the next 30 years. Subpoenas have been pending for some time at the SEC and the case is being pressed in two lawsuits on the matter. At issue are Peabody’s wildly optimistic projections and estimations that sold Prairie State as a source of cheap electricity to towns and cities now being crushed by the deal. Peabody’s behavior was abominable and has not been forgotten: it promised the moon on that project, built it and then walked away.

But why look backward?

PEABODY TODAY IS PART OF A GROWING LIST OF COAL PRODUCERS LOBBYING HARD AGAINST REGULATION OF GREENHOUSE GASES. These companies’ strategy is to dismiss the effect of climate-altering emissions as “a non-existent harm” and “benign gas” and by arguing that new regulations are misguided because they’re based on computer error.

One can only hope that the judges who review coal industry pleadings from here on out understand that they are looking at information that is false, misleading and manipulative. And one can hope, too, that regulators in Washington, elected officials with decision-making authority, and the plethora of journalists and editors who write about Peabody will do a better job of questioning industry pronouncements in this area. Regulators and decision makers in other countries would do well, too, to take another look at Peabody’s representations on mines, ports and other holdings.

Although the agreement with the New York attorney general speaks to future risks, investors would do well to remember that these risks are manifest already (“Wyoming Regulators Say Peabody Complies with Self-Bonding Requirements, but They Don’t Say How,” “Seeing Through Peabody’s Attack-the-Messenger Strategy,” and “Asterisks: Taints in Peabody’s Financial Reporting”). Peabody’s current filings are full of distortions about climate science, coal markets, prices, reserve levels and of course the impacts of regulations on the coal industry. Central to Peabody’s arguments is that regulations are what are destroying the coal industry, an assertion that ignores rising competition from natural gas and renewables—forces that have stripped coal of its market share and will continue to do so. The broad and growing willingness to embrace other forms of energy for electricity generation is based in part on money and in large measure on the inability of the coal industry to produce a fuel that is safe.

So—again—the risks cited by the New York attorney general are not future risks. Coal plants cannot get financing now—and that in the absence of any carbon tax. The World Bank says it has stopping funding coal plants and in the U.S. new plants aren’t viable in large measure because no bank will finance them.

The industry is also facing major risk posed by divestment campaigns, which are not futuristic at all. They are happening now. The largest institutional fund in the world, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global, this year divested from coal “In Norway’s Divestiture, Coal’s Shabby Finances Matter; Executive Intransigence Is a Factor Too”). The New York City Mayor’s Office has put coal divestment and climate change initiatives in place recently and the California legislature this fall enacted legislation to divest from coal (“The Financial Case for CalPERS and CalSTRS to Get Out of Coal”). A slew of faith-based, foundation-owned and other big funds have divested. University divestment campaigns are widespread. Just counting the large institutional investors, over $1 trillion in investment muscle has already moved away from coal. This, too, is hardly a future risk.

Ultimately, the attorney general’s agreement with Peabody goes to the company’s integrity, which remains suspect. Vic Svec, the company’s spokesman, admits nothing in the Times article, indeed proudly emphasizing that “there is no acceptance or denial of their findings.”

It’s notable, though, that the company hasn’t denied misleading the public and its investors.

It’s sadly typical of Peabody, and it sounds a loud buyer-beware alarm for any government agency or investor with an interest in Peabody’s official filings now or in the future.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.