Oil producers face profit squeeze amid shifting policy landscape

Key Findings

A recent survey reveals a dark mood in the fossil fuel sector, as tariff talk shakes industry confidence.

Yet the oil industry’s challenges go deeper than the current political moment.

Amid weak margins and rising costs, fossil fuel producers are facing a profit squeeze.

The industry’s balancing act of extracting more carbon, generating a good profit, and maintaining political legitimacy is getting harder.

Judging by the news headlines heralding a new “drill, baby, drill” era, you’d think the oil and gas executives would be feeling a rush of euphoria these days. Yet a Dallas Federal Reserve Bank survey of oil and gas insiders reveals a darker mood. Speaking anonymously, respondents confessed to being rattled by an ever-shifting policy landscape, even as they’re squeezed between low prices and rising drilling costs.

As one summed it up: “I have never felt more uncertainty about our business in my entire 40-plus-year career.”

The industry insiders pinned part of the blame on tariffs. Said one: “Uncertainty around tariffs and trade policy continues to negatively impact our business.” Lamented another: “Tariff policy is impossible for us to predict.” A third agreed, saying that “[T]ariff policy is injecting uncertainty into the supply chain.”

But tariffs are only a part of the industry’s problem: Its deepest challenges are structural, not just political. Weak global demand is keeping prices low. Drilling costs are rising. And producers are starting to run short of top-quality drilling opportunities.

If there’s any solution to this grim trilemma, it has escaped the industry’s notice.

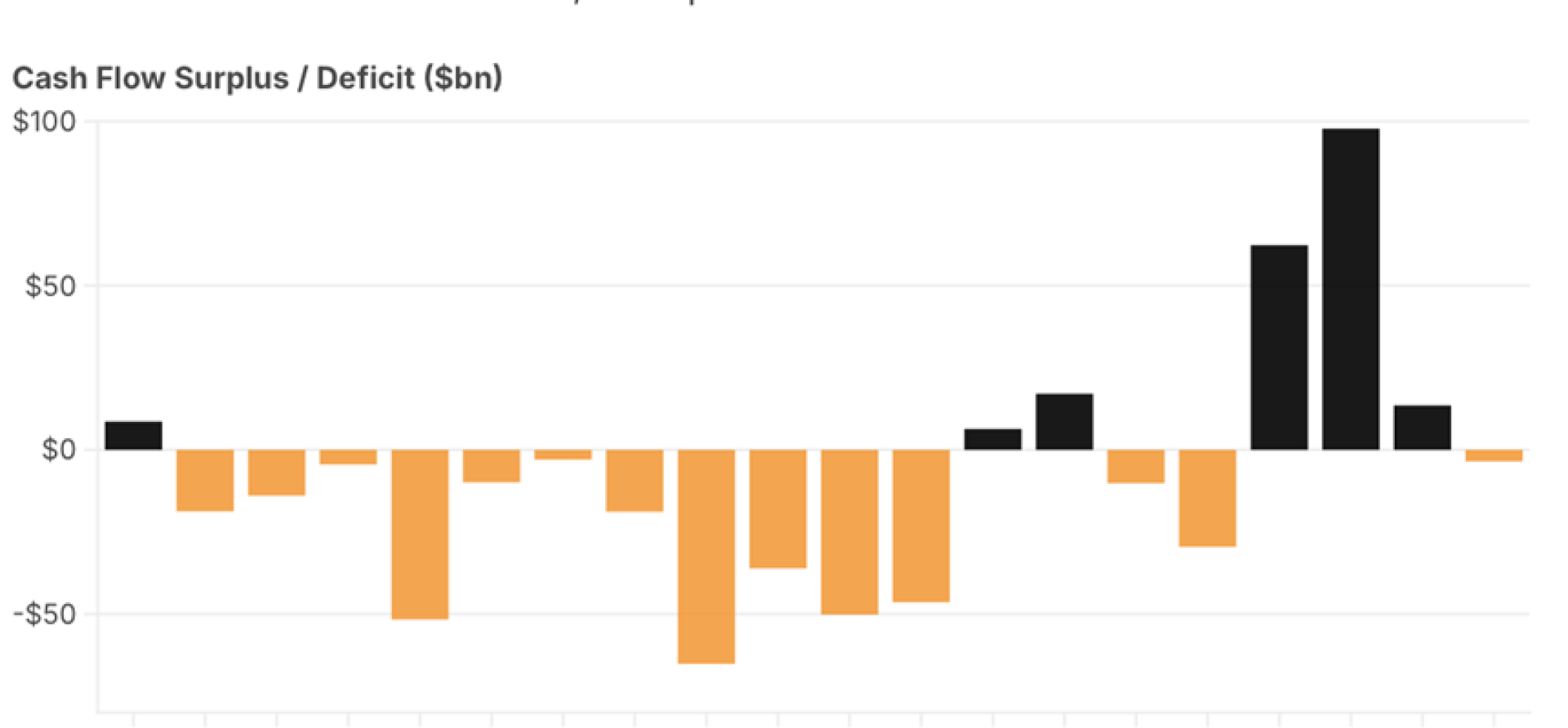

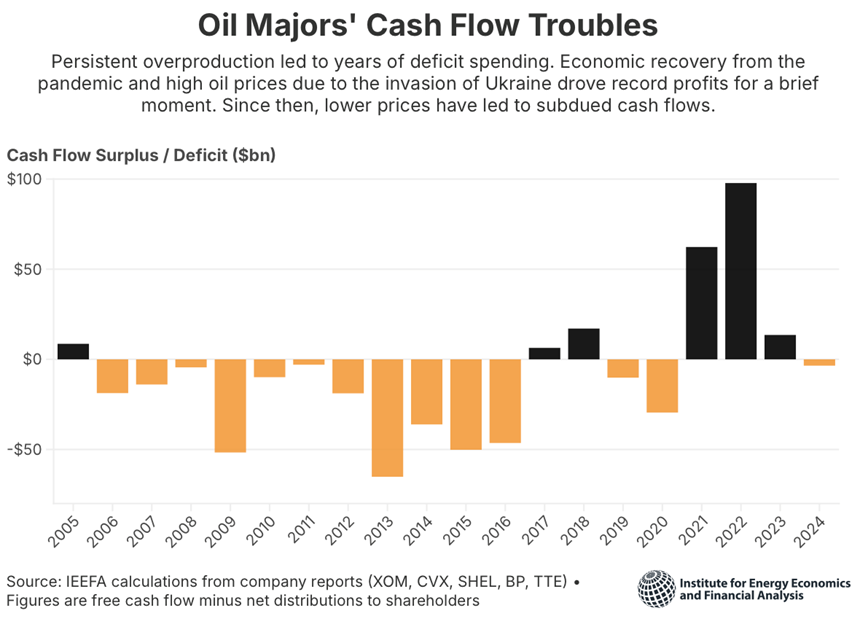

While today’s politics create new uncertainties, weak profits have underscored a longstanding quandary. Throughout the 2010s, aggressive oil and gas drilling flooded a saturated market. Prices plunged, profits narrowed, and cash flows dried up. Many companies spent more than they earned, borrowing money to keep both oil and dividends flowing. In the process, they burned through billions of dollars of shareholder value.

Things improved for the industry in the early 2020s. Global oil demand cratered in 2020 during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing drillers to slash spending and trim output. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine sent energy prices soaring, fueling record oil and gas profits. To some, it was a sign that the industry had gotten itself back on track.

Yet high prices came at a cost to the industry, spurring cutbacks in consumption and gains in energy efficiency. Competition grew as markets saw a surge in global electric car sales and record growth in renewables. Even OPEC warned at the time that these higher prices could hinder oil demand and incentivize lower-carbon substitution. By 2023, JPMorgan Chase analysts noted the clear evidence that “demand destruction has begun.”

The crises-era windfalls now lie in the rearview mirror, and despite gains in oil and gas output, the industry’s profits have sagged. Traditional energy, in fact, has seen one of the weakest comebacks of any S&P 500 sector since the equity markets trough in 2022.

Meanwhile, breakeven prices—the level needed to justify new drilling—have crept upward, squeezing corporate profit margins. “The U.S. oil cost curve,” as one Dallas Fed survey respondent put it, “is in a different place than it was five years ago … $70 per barrel is the new $50.” Rystad, too, recently noted “increasing cost pressures on the upstream industry,” while Citibank predicted that the industry would have to shut down drilling rigs if prices fell too much further. Tariffs (real or threatened) are only heightening this problem, provoking cost increases in materials and equipment needed for drilling while causing economic jitters that depress demand.

And even though today’s $70-a-barrel price may be barely high enough for oil companies to tread water, the industry still faces calls to drill yet more oil to bring prices down. Producers can’t pull this off without repeating the red ink fiasco of the 2010s. But ignoring the calls altogether may have an effect on industry and government relations.

The unpredictable policy terrain isn’t helping, rendering capital planning an exercise in dart-throwing. But even if the industry can manage to navigate the near-term minefield, its core problems remain. Fossil fuel producers face simultaneous mandates to extract more carbon, sell it at a competitive price, generate a good profit, and maintain political legitimacy. For oil executives, it’s a balancing act that is getting harder all the time.