More credit downgrades imminent under climate change but credit model overhaul yet to be seen

Key Findings

Rating agencies have come a long way in addressing credit risk for fossil fuel-related debt issuers and sectors. While it is a good step in the right direction, more can still be done.

IEEFA has proposed potential approaches in adjusting, not redeveloping, the existing rating model to ensure long term climate risks are integrated and effectively reflected in credit ratings today. Climate-adjusted ratings, or assigning appropriate weightage to climate risks as part of the existing rating system, could ensure rating stability and predictability in the long term.

In addition to improved climate data and credit analysts with sustainability expertise, the credit rating committee could expand the time horizon of their assessment and integrate sufficient analysis of future earnings scenarios or anticipated impact to cash flows from a climate risk perspective.

Climate risks may be on the verge of lowering credit ratings while assessors of debt issuers dawdle on a rethink of their evaluation models. The outlook is bleak but bearing down on the bond market with previously unexpected momentum.

Last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released the final installment of its Sixth Assessment Report. One of the grimmest findings is that the effects of climate change are already more widespread and severe than feared.

Climate-related credit risk will be more prevalent than ever before. Credit rating agencies (CRAs) Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, and S&P Global Ratings have themselves acknowledged that environmental, social and governance (ESG) credit risks, particularly those induced by climate change, will increasingly undermine the issuer’s credit profiles.

What does this imply?

More rating downgrades are ahead if exposure to climate vulnerabilities is not mitigated. In particular, industries that are highly exposed to climate risks may face lumpy asset value deterioration and disruptions to operations and supply chains. Consequently, the cost of capital could rise if investors lose confidence in the company’s ability to manage the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Fitch’s Climate Vulnerability in Corporate Credit Ratings – Discussion Paper, also published last month, describes a screening tool in its rating process that provides a long-term view of transition risk for investors. Using the tool, Fitch concludes that by 2035, almost 20% of global corporates could face rating downgrades if such a risk is left unmitigated. However, a 2020 study showed that a firm’s creditworthiness was already being affected by exposure to climate risks, suggesting more downgrades could occur before 2035.

While the screening tool is a step in the right direction, more can be done to ensure credit ratings adequately reflect long-term and systemic climate risks today.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) has highlighted in a report that while CRAs consider climate risks to be material, these factors have little impact on assigned credit ratings due to the relatively short-term nature of the assessment.

Because the problem is downplayed, an issuer that faces heightened climate risks in the long term may experience an abrupt and sharp rating change sooner than expected. Therefore, bond investors, including those who do not prioritize climate change mitigation, are unknowingly exposed to the increasing impact of climate-related credit risk.

There may be challenges integrating climate risks into the conventional credit assessment model, and a complete overhaul would take time and effort. But CRAs can adopt near-term alternatives to adapt to the changing world, such as climate-adjusted ratings or assigning appropriate weightage to climate risks as part of the existing rating system, to ensure rating stability and predictability in the long term.

Giving credit where credit is due

Rating agencies have come a long way in addressing credit risk for fossil fuel-related debt issuers and sectors.

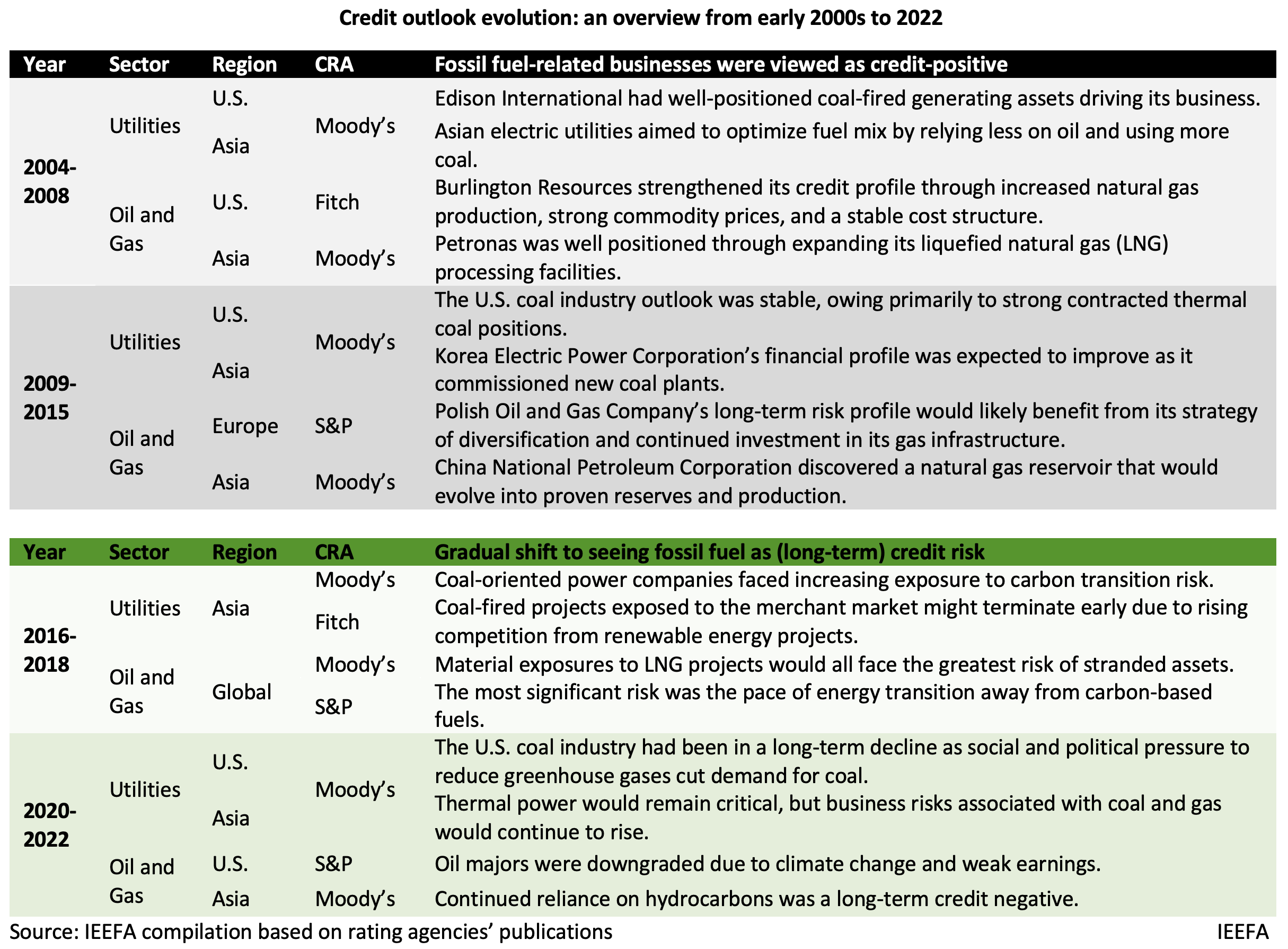

IEEFA’s credit outlook research from 2004 to 2015 found that Fitch, Moody’s and S&P viewed the coal industry as credit positive, including the commissioning of coal plants, increased production, reserves, and capacity for hydrocarbon resources.

In recent years, however, IEEFA has observed a change in their stance. Presently, CRAs consider that the coal industry is in a long-term decline due to social and political pressures arising from the drive to reduce greenhouse gases. Natural gas investments and continued reliance on hydrocarbons are also seen as long-term credit risks.

These examples demonstrate how CRAs’ perspectives on evaluating fossil fuel-related businesses have evolved over the last two decades. What was once considered credit positive is now viewed as a potential credit risk.

Having come a long way, rating agencies have a long way more to go

Credit rating agencies are starting to consider climate-related risks, but more tangible rating action is needed.

Evaluations are still largely based on current events revolving around policy changes and market forces. This may be adequate for short-term investors and credit assessments of three to five years. However, the system does not work well for investors that take a long-term view, as higher emission costs and risks of stranded assets, refinancing, physical events and transition become increasingly evident. There is a need to prevent cliff-edge rating downgrades and sweeping bond sell-offs.

This calls for improved climate data, a more diversified composition of credit rating committees, and credit analysts with sustainability expertise. The committees should also expand the time horizon of their assessment and integrate sufficient analysis of future earnings scenarios or anticipated impact to cash flows from a climate risk perspective.

IEEFA has proposed some approaches in adjusting, not redeveloping, the rating model to integrate and reflect long-term climate risks effectively in credit ratings today. Just as corporations and risk managers are expected to think long-term, credit assessment practices must evolve to ensure that the rating system, too, is sustainable.