Methane abatement: One coalmine’s waste is another’s valuable resource

Key Findings

Investing in methane mitigation measures can protect business sustainability and generate value.

Despite this, little has been invested in this area recently in Australia amid miners’ record profits and returns paid to shareholders.

Some miners are progressing investment in methane abatement because it makes economic sense and offers first mover advantages.

Coalmine methane emissions have long been viewed as a cost to be minimised rather than a valuable resource. That could be about to change. Methane from coalmines can be a valuable resource if it is captured and used, rather than released into the atmosphere.

Australia has a long history of coalmining, stretching back over a century. For nearly three decades, some coalmines have captured methane and used it to generate electricity at on-site power stations. But widespread methane abatement across the industry has been slow. Only 12 of the 40 operational underground coalmines in Australia have some abatement. For the 60 open-cut mines, there are only a handful of trial projects.

One reason is the high upfront cost. The capital outlays and financial commitments for gas drilling and drainage infrastructure can be significant, and methane abatement is not their core business. While there are rules encouraging best practice, it has been difficult for regulators to enforce these rules or provide enough financial incentives.

Most major coalmining companies in Australia have focused on returning profits to shareholders, through dividends and share buybacks or on coalmine growth or acquisition.

For early adopters, grant programs such as the federal government’s Powering the Regions Fund (PRF) and Queensland’s Low Emissions Investment Partnership (LEIP) are available to subsidise upfront capital costs. With such support, capturing methane from coalmines can be a viable choice, turning a waste problem into a valuable opportunity.

As a result, some coalminers are turning their attention to methane abatement because it makes economic sense. Apart from the financial support available and the potential to reduce emissions, they can also benefit from turning a waste product into a source of income or to offset some mining energy input costs.

These projects are more the exception than the rule. Amid net-zero goals, ambitions and discussion of future carbon reduction strategies, actual progress remains rare, according to miners’ annual sustainability reports (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Coalminers’ methane abatement status (mentions in 2024 sustainability reports)

Source: Coalminers’ annual sustainability reports 2024. Note: Page mentions exclude glossary, definitions, footnotes, disclaimers or explanatory statements. Dark shading refers to actual activities under way or strategies under consideration.

BHP’s 2024 Climate Transition Action Plan addressed methane abatement most comprehensively but it remains a future consideration. However, some miners are taking concrete steps to capture and use methane.

Anglo American has invested significantly in methane abatement at its Queensland metallurgical (met) coalmines. It captures gas before and during mining, and abated approximately 60% of its reported methane emissions in 2023. With improved goaf sealing practices, it abated up to 70% of those emissions in 2024. Anglo has spent more than US$100 million a year on gas mitigation infrastructure (or about US$20 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent/tCO2e). It is also investigating Ventilation Air Methane (VAM) abatement in conjunction with the University of Newcastle, funded by A$35 million in grants from Low Emissions Technology Australia. However, the continuation and completion of these projects will ultimately depend on the mines’ ownership. US-based mining giant Peabody was due to take over the mines from July 2025, but may back out of the deal following a methane incident at the Moranbah North mine in Central Queensland.

Coronado Resources is investing in methane abatement at both its US and Queensland mines. At its Curragh open-cut mine, it is trialling pre-drainage of methane. The captured gas is used to reduce the need for diesel in haul trucks, further reducing emissions.

Stanmore Resources is investing in capturing methane to generate electricity at its South Walker Creek open-cut mine in Queensland. According to its 2024 Sustainability Report, “By harnessing the methane that would otherwise be released as fugitive emissions, we will convert it into on-site power for the mine.”

EMR and Adaro’s Kestrel Mine in Queensland plans to use methane to fuel a new power station, with support from LEIP funding. It has also announced a commercial-scale VAM abatement project, with 50% grant funding of A$37 million from the Powering the Regions Fund. It is reported that the full capital cost of Regenerative Thermal Oxidation (RTO), before funding, is as low as A$9.24/tCO2e or about A$15/t over 10 years.

These examples show that methane abatement can be technically and economically viable at both underground and open-cut coalmines, which is supported by recent academic studies.

In open-cut mines, a study by the University of Queensland’s Gas and Energy Transition Research Centre found methane abatement was economically viable in a range of scenarios, including: (1) flaring the gas, (2) selling it, (3) generating electricity and (4) displacing diesel in mining operations. Displacing diesel also has the highest emissions savings potential.

In underground mining, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe found methane abatement using VAM was economically viable where there was a price on carbon emissions of US$20/tCO2e or higher. This compares with the spot price of A$35/tCO2e (US$22) for Australian Carbon Credit Units.

Kestrel Coal’s VAM project partner, Peak Carbon, reported that while some safety and technical considerations remain, it estimates, “three quarters of underground coal mines could meet the likely risk analysis criteria for installation of RTO projects”.

The business case

The process for building a business case for methane abatement in coalmining generally follows several clear stages. Like other mining projects, it starts with a concept or options study then moves though feasibility stages before reaching a final investment decision.

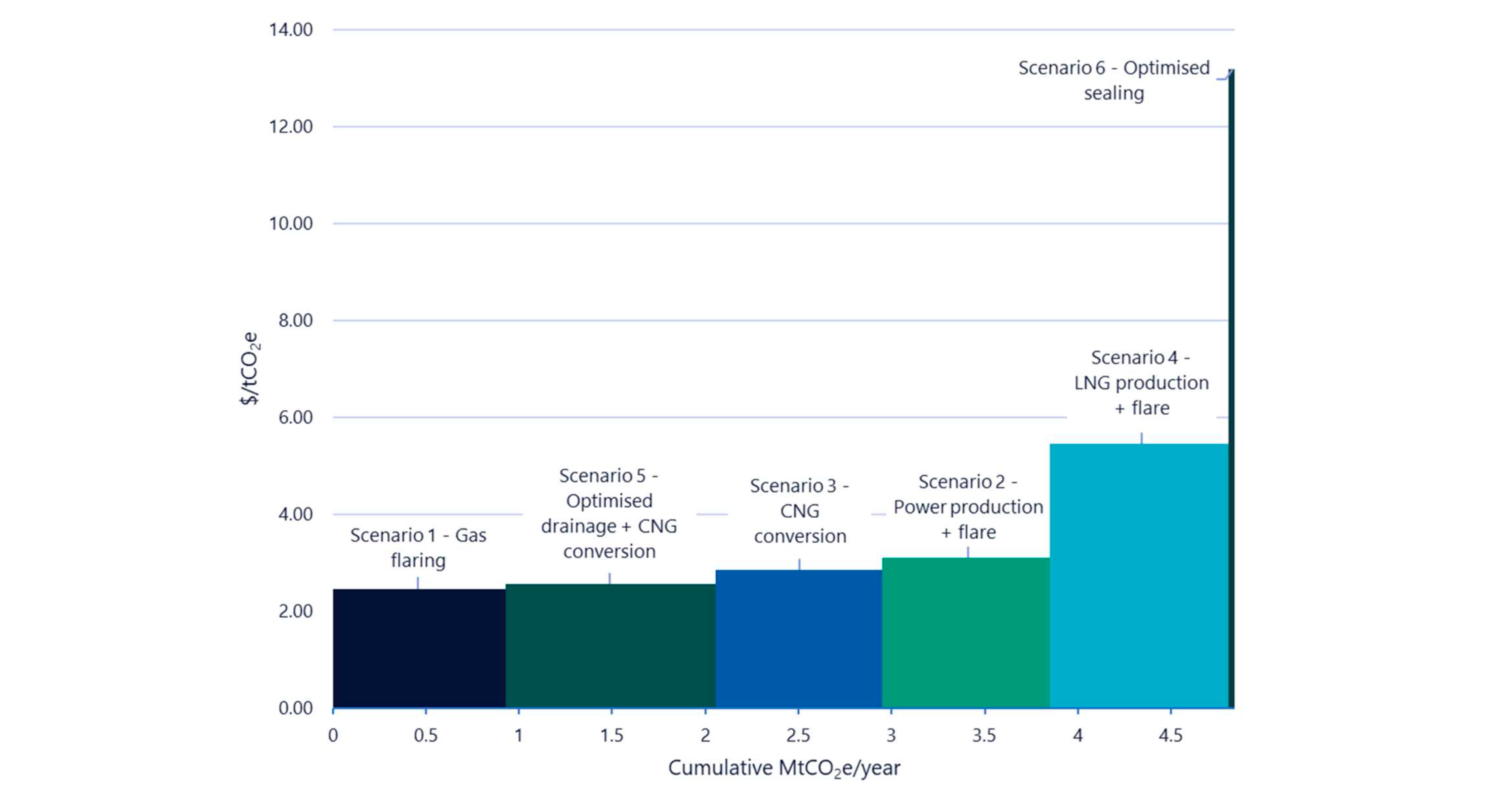

An initial assessment of the relative costs and benefits of each scenario can be determined by constructing a Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC). Here the net present value (NPV) of the abatement scenario is divided by the volume of CO2e tonnes abated. The resulting net cost per tonne of each alternative can be ranked by cost and abatement potential. For example, Coronado has done an MACC analysis of the costs and extent of different gas use options to prepare the business case for methane abatement (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Coronado Resources MACC analysis for Mammoth Underground scenarios

Source: CURRAGH BORD AND PILLAR MINE PROJECT EAR GHG REPORT, 2024, Figure 5. Note: CNG = compressed natural gas.

Another output of the business case is a discounted cashflow analysis of the abatement investment. This involves comparing the financial costs and benefits of running the business with and without the methane abatement project. For instance, evaluating the costs of operating haul trucks on diesel alone versus using captured gas to replace some of the diesel. Costs are incurred for gas drainage, compression, storage and refuelling. Some third-party operators might take on the capital, and package some of these costs into an operating cost (e.g. on a dollar per litre of diesel replacement basis). Operational impacts also need to be considered, for example the impact of changes to refuelling operations and its impact on productivity.

Meanwhile, technical studies are carried out to assess the amount of gas that can be captured and how best to do it. This may require further sampling and testing in (an extended) gas drainage trial phase. For VAM projects it will require a forecast of methane emissions from a vent shaft.

Co-ordinating the supply of captured methane with the demand for its use can be challenging. The timing of when gas is available does not always match up with when it can be used. For instance, if a mine is considering whether to use methane for a power station or for haul trucks, the decision might be affected by when the trucks are due for replacement or whether electric alternatives are being considered.

However, such complexities need not slow down decision-making. A practical approach is to build flexibility into investment decisions. Rather than waiting for perfect certainty, miners should factor in uncertainty. This enables them to proceed with, for example, the gas drainage stage while they wait for information to become available on the highest and best use of captured gas. That way they can develop and make the most of methane resources, and set up the best sustainability option for the long-term success of their operations.

The main issue is that methane abatement is considered optional. Regulatory settings tip the balance in favour of purchasing carbon credits to offset any emissions reduction obligations they might encounter under the federal government’s Safeguard Mechanism. Apart from that, there are no environmental obligations inhibiting continued methane releases.

At mine sites, methane abatement can be overlooked for fear of interfering with coalmining operations, disruptions to mine planning and safety hazards. At the corporate level, emissions reduction targets and reporting methods, and the Safeguard Mechanism have created uncertainty.

The International Energy A's Agency (IEA)’s Global Methane Tracker, 2025 report highlights the ongoing challenge to reduce methane emissions from fossil fuel operations. It finds historical trends are largely unchanged, with the coal industry lagging and methane emissions under-reported. Outlining the barriers to abatement, it said, “companies could be unaware of the scale of the problem or the available solutions. There may be higher-profile opportunities competing for investment resources, or leadership may perceive methane abatement as more costly than it is ... or may not have identified an effective pathway or business case for bringing captured gas to productive use.”

The IEA suggests companies stimulate abatement. They “could integrate methane-specific performance indicators into their financial and operational strategies (such as tying them to employee and executive compensation). They might also consider establishing an internal price for methane when making capital investment decisions.”

In an evolving regulatory landscape, coalminers should view methane abatement as an opportunity to transform a waste problem into profit while strengthening their social licence to operate.