Kemper Power Plant, a Debacle That Should Never Have Been

By David Schlissel

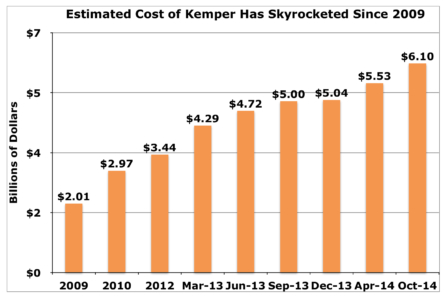

It’s pretty well known that cost overruns at Mississippi Power’s new plant in Kemper County now total $3.1 billion, roughly 100 percent more than the estimate the company put forth when it received approval in early 2010 to go ahead with the project, which was completed last year.

What isn’t as publicized is how Mississippi Power ignored signals that those overruns were bound to happen.

When I testified at the Mississippi Public Service Commission proceeding in 2009 at which Mississippi Power requested permission to build Kemper, I noted the significant risk that the costs could be substantially higher than Mississippi Power estimated. I based this warning on two fundamentals:

- The skyrocketing costs of building new coal plants in the U.S. in general;

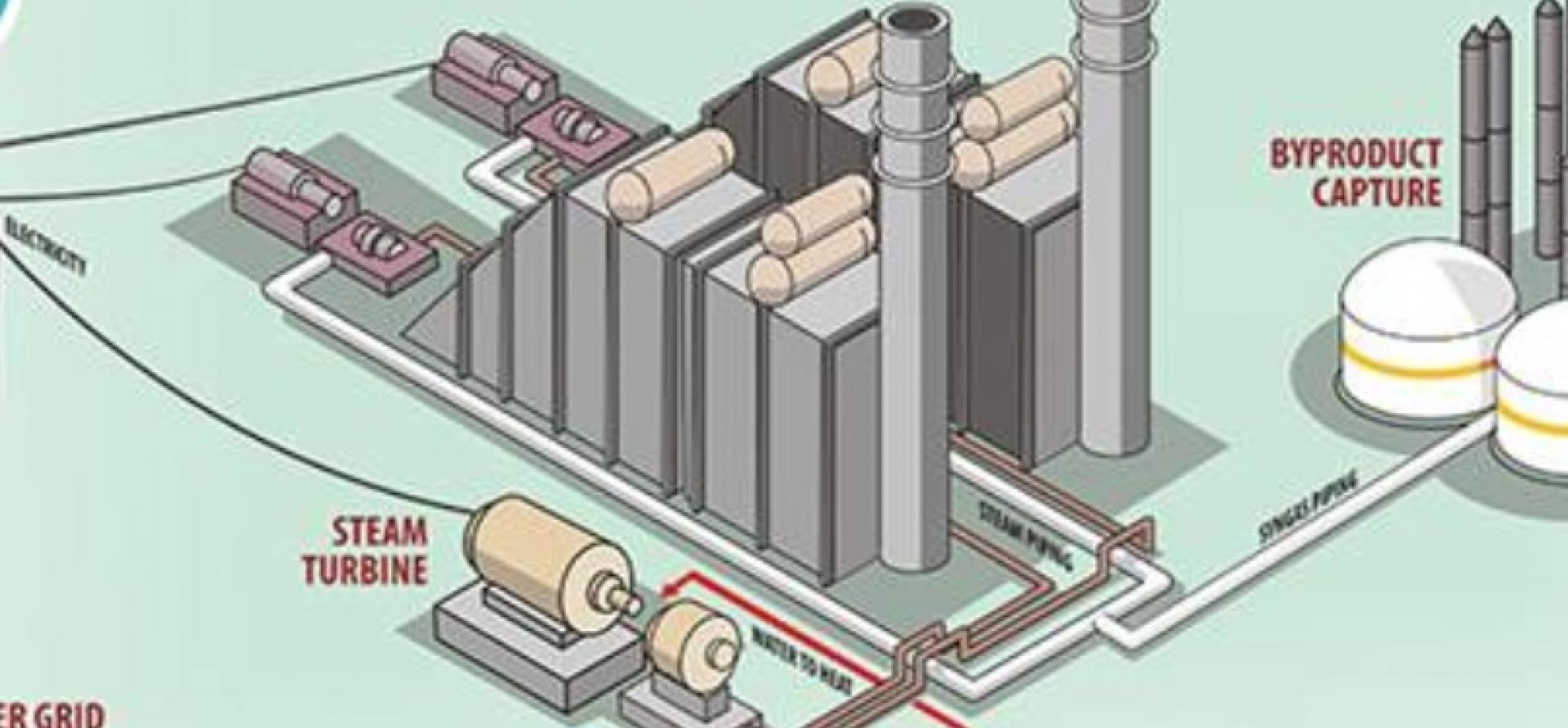

- The use of new and untested integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) technology at Kemper.

I wasn’t alone in my skepticism. It was widely accepted across the industry by 2009 that coal plant construction costs had not only gone through the roof but were likely to continue to rise. Kemper was subject also to “first-mover risk” as one of only two plants with new IGCC technologies to begin construction in the U.S. since the late 1990s. The industry as a whole was aware of the risks, challenges and uncertainties facing companies that invested in IGCC, and it was generally recognized by 2009 that IGCC projects were vulnerable to dramatically increasing capital costs.

Because of those risks, all but two 27 IGCC projects proposed in the U.S. were cancelled or placed on indefinite hold. Kemper was exposed also to risk related to its adoption of a fast-track design and construction schedule, which allowed construction to begin before the final plant design was completed. Fortunately — on that point — the Mississippi PSC did set a cap on construction-cost overruns at Kemper, requiring the parent company, Southern Company, to bear that burden.

In testimony and affidavits filed in 2009 and 2012 with the Mississippi PSC, I warned of other risks, too:

- That natural gas prices would be substantially lower than the company foresaw in its viability analyses;

- That the company would have less of a need for the power from Kemper due to either reduced demand, changes in energy forecasts or cancelled plant retirements;

- That the plant’s untested IGCC technology would keep it from operating as well as forecast;

- That carbon dioxide emissions prices would ultimately be higher than the company assumed;

- That sales of byproducts from the gasification and combustion processes at Kemper would not produce the revenues that the company was projecting.

All of these risks have materialized—even though Mississippi Power executives said they would not—and the result is a debacle that should never have been built. Customers are still paying ultimately at least $3 billion for a power plant that was shown as long ago as 2009 to be a much more expensive alternative than other sources of electricity.

The upshot is that customers are stuck with much higher rates—for decades to come—because of an expensive, untested and perhaps unreliable plant—and one they may never need.

David Schlissel is IEEFA’s director of resource planning analysis.