Japan does not need Australian LNG to keep the lights on in Tokyo

Key Findings

The Australian government’s Future Gas Strategy anticipates continued demand for LNG exports, but IEEFA research suggests our biggest export market, Japan, is already in decline and over-supplied.

Japan’s LNG demand dropped by 25% since 2014 and is expected to drop by a further 25% by 2030.

Japan is already over-contracted in LNG, and resells more LNG overseas than it imports from Australia.

Japan will have many suppliers to choose from in a soon-to-be-oversupplied global LNG market dominated by low-cost producers.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

Released last week, the Australian government’s Future Gas Strategy states that “our trade partners […] are relying on Australian gas to transition their economies to net zero”, but falling demand and over-contracting from Japan, our largest LNG export customer, raise questions over this claim.

Japan has on several occasions stressed the importance of Australian LNG for its energy security. Last year, Japan’s ambassador to Australia said: “It’s hard to imagine the neon lights of Tokyo ever going out, but […] this is exactly what would happen if Australia stopped producing energy resources.”

However, IEEFA research suggests that Japan does not actually need Australian LNG. Japanese LNG demand has already dropped by 25% between 2014 and 2023, and is expected to drop by a further 25% by 2030 to about 50 million metric tons per year (MTPA).

IEEFA’s recent Global LNG Outlook 2024-2028 explains the factors behind the recent decline and why it is projected to continue. The recent decline was “primarily due to lower demand in the power sector, where rising nuclear availability, declining power demand and higher generation from renewable resources reduced the call on gas-fired generation”.

The report goes on to state: “In 2023, gas generation fell 9% and city gas sales fell 4.4%. Renewables generation increased 5%. The government’s Sixth Strategic Energy Plan calls for a reduction in LNG-fired generation from 394 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2019 to 187 TWh (-53%) by 2030. IEEFA estimates that realizing this plan could decrease LNG imports by between 25.7 MTPA and 31.6 MTPA from 2019 levels.”

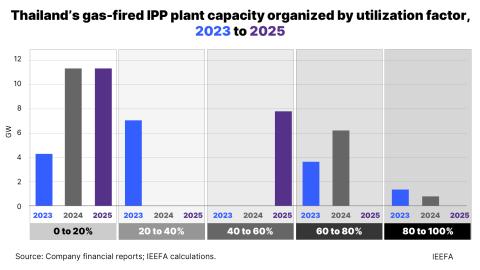

Figure 1: Japanese past and estimated LNG demand under Japan’s sixth Strategic Energy Plan (left) and operable nuclear capacity (right).

Source: IEEFA.

Nuclear generation in Japan has been steadily increasing as reactors are progressively brought back online. Two units were restarted in 2023 and the active fleet also increased its utilisation. Another 11 reactors are undergoing review.

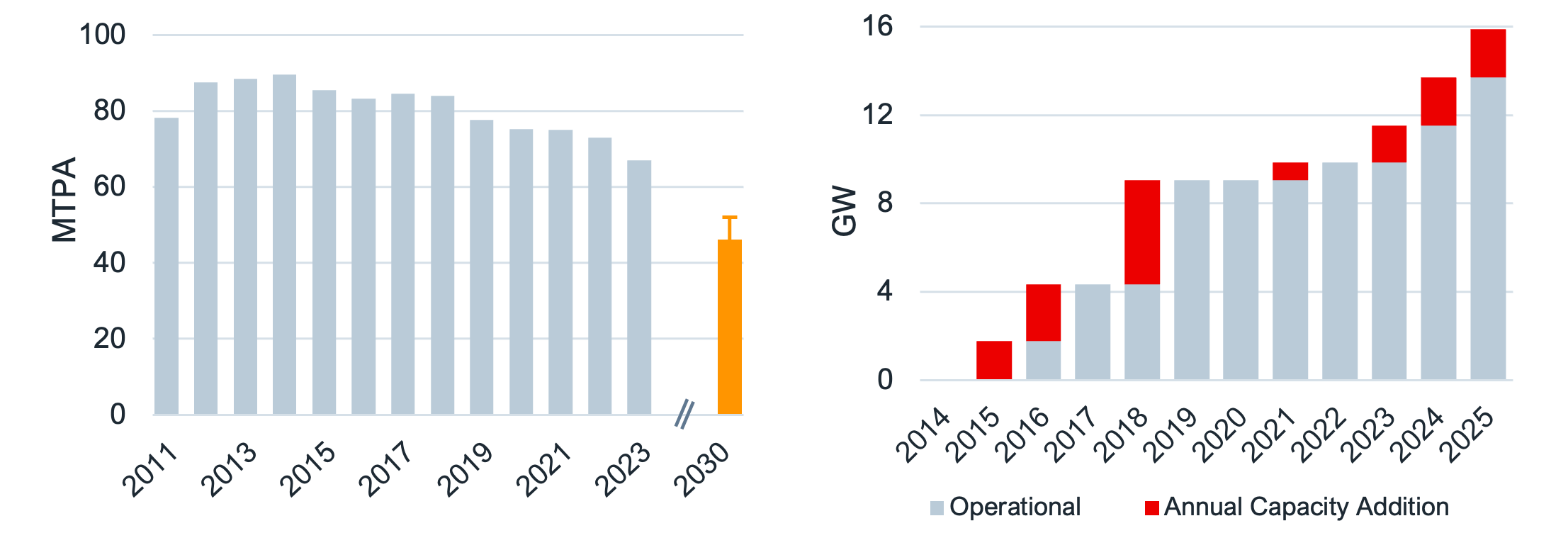

The resultant fall in LNG demand means that Japanese buyers have found themselves over-contracted, and are increasingly reselling the gas overseas. IEEFA has found that Japanese companies sold more than 30 million tonnes (mt) to third countries in FY2020, FY2021 and FY2022, peaking at 38mt in FY2021. This is more than Australia’s total LNG exports to Japan over those three years.

The surplus LNG is often sold in Southeast Asia where Japanese utilities are cultivating demand. IEEFA found that Japanese “utilities are investing in midstream and downstream gas infrastructure, such as regasification terminals and LNG-fired power plants and offering engineering and consulting services to inform energy and power roadmaps across the region. […] Corporate strategies for Japan’s major LNG buyers aim to tilt revenue share towards overseas revenues.”

Figure 2: LNG sales by Japanese companies to third countries compared to Australian LNG exports to Japan, mt

Sources: JOGMEC; Australian government, Department of Industry, Science and Resources.

JERA, Japan’s largest electricity producer and one of the world’s largest importers of LNG, has acknowledged this shift. Its new global chief executive officer and chairman said in an interview that looking ahead the company’s transaction volumes “may decline or may stay the same”, and that “Japan may not need LNG for 20 years ... but other Asian countries need to replace coal with something and LNG will play an important role.” He added that JERA could supply fuel to those countries likely to need it.

Over-contracting and reselling of gas is expected to increase in the coming years. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has set a target for Japanese companies to transact 100mt of LNG by 2030, well above projected domestic demand, and has been promoting trading with third countries. The Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) Act was revised to allow JOGMEC “to make direct investments or provide debt guarantee to Japanese companies participating in projects that are building and operating LNG receiving terminals in third countries”.

It therefore seems that Japan may not need Australia’s LNG to keep the lights on in Tokyo, contrary to what the Japanese ambassador suggested, but rather to support its trade with the region. In the process it could effectively become a competitor to Australian LNG producers for sales opportunities in emerging Asian markets.

Another factor that calls into question Japan’s need for Australian LNG is that the world is facing an LNG supply glut in the coming years. IEEFA expects global LNG supply capacity to increase by 40% by 2028 due to an unprecedented wave of new projects coming online.

This increase in capacity will happen at a time when demand from some of the largest LNG markets is expected to decline. Europe, Japan and South Korea, which represented more than half of global LNG consumption last year, are expected to see falling demand to 2030. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), China is also expected to be over-contracted in LNG by 2030. Emerging Asian markets are facing a range of challenges to support LNG demand growth. IEEFA found that the LNG capacity coming online through 2028 exceeds long-term LNG demand in the IEA’s most conservative scenario, aligned with a 2.4°C future.

A sign of the growing misalignment between supply and demand is that much of the new supply is yet to find end buyers. Much of the output from Qatar’s expansion is uncontracted, which may lead to spot-market oversupply. In addition, portfolio players (intermediaries) are now the largest signatory of LNG contracts. However, portfolio players have committed to buying about twice as much LNG as they have sold, betting on future LNG demand that may not materialise.

The majority of new LNG projects will be built in Qatar and the United States, which both have production costs well below Australia's. In this context, there is not a clear value proposition for new Australian LNG projects. Australia’s government may want to think again before building a long-term gas strategy on lasting demand for exports.

This article was previously published in ReNew Economy.