Indonesia dances around taxonomies to mobilize capital for its coal phaseout programs

Key Findings

The inclusion of coal phaseout activities into the Tier 1 (Green) bucket in the ASEAN taxonomy version 2.0 confirms most climate finance experts’ fear that political considerations override disciplined scientific-based rationales.

The usefulness and credibility of any taxonomy rests on a number of policy and market variables. Green labeling will only be credible when definitions of activities or assets are not only science-based but also technically and financially viable in a specific market context.

Taxonomies are only one part of the financial equation when it comes to mobilizing capital. Indonesia's decarbonization pathways need to be economically and socially feasible, and reflected in a realistic timeframe.

Mere tweaks to criteria for supporting early coal retirement may not be enough

Since Indonesia signed the US$20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) agreements late last year, the government has mobilized multiple workstreams to create policy structures needed to support the critical first stage, of early coal retirement.

The JETP is a key initiative in Indonesia’s emission reduction, keenly observed and supported by foreign stakeholders. It has raised important questions about how to manage trade-offs between short-term domestic priorities and long-term international market preferences in the first transactions.

The government is putting together a comprehensive investment plan (CIP) to fund its net-zero aim. Due in August, the CIP will list power plants, both coal and renewables, to be offered as a menu to potential investors.

At US$20 billion, the JETP was impressive when announced, but it is not nearly enough to finance the significant decarbonization needed by Indonesia. For the power sector alone, the state utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara has repeatedly stated a need for at least US$500 billion to reach its net-zero goal by 2060, far surpassing the state budget’s funding capacity.

Everyone seems to be on the same page regarding the importance of private capital to fill the financing gap. The problem is, while interest in clean energy investments has been strong, little appetite is apparent for the “dirtier” deals focused on early coal retirement.

Indonesia’s Finance Minister Sri Mulyani acknowledged as much during an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) ministerial discussion on financing transitions late last month. She noted that many of the global investors had grown allergic to adding fossil fuel assets to their portfolios due to rigid environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics that did not accommodate brown-to-green transition strategies.

One solution often touted by regulators is creating a robust transition finance framework tailored to Indonesia. Such a framework would, importantly, include a taxonomy that classifies which economic activities and assets are “green” or environmentally sustainable, and what are acceptable as “brown-to-green” transition activities.

The best taxonomies create certainty for investors, but they are only one part of the financing equation. The question is how stringent Indonesia should set the transition criteria, taking into account a pressing need to not only avoid charges of greenwashing or “transition washing,” but also build confidence in the country’s decarbonization pathway.

It is critical for Indonesian policymakers to formulate science-based transition taxonomy screening criteria to attract reputation-sensitive investors to support the CIP.

Red flag in latest ASEAN taxonomy

Late last month, ASEAN issued version 2.0 of its Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. The new edition, built on the original traffic-light classifications, offers two approaches to assess an activity: the Foundation Framework, which is a principle-based assessment with qualitative guiding questions to determine whether the activity is Green, Amber or Red, and the more rigorous Plus Standard (PS), which uses quantitative threshold-based technical screening criteria (TSC).

The TSC’s first focus sector is energy, covering electricity, gas, steam and air-conditioning. Not surprisingly, this is where investors may find a red flag. The ASEAN taxonomy adopts early coal phaseout as part of transition activities, but proposes classifying it as Tier 1 (Green) under the PS framework if the coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) satisfy these specific conditions:

How a coal phaseout can qualify for Tier 1 (Green)

Time of phaseout by 2040; built before December 31, 2022; operation duration maximum 35 years after commercial operation date; demonstrate the adoption of best-in-class technology (provided that these technologies are affordable, accessible, reliable and can be implemented within a reasonable timeframe); and demonstrate substantial absolute positive emissions savings over their expected lifetime (which should be verified or acknowledged by internationally recognized bodies or programs).

What stands out is that the TSC reflects terms of coal plants that are under deliberation for the Asian Development Bank’s energy transition mechanism (ETM) or the JETP early coal retirement program. Adopting it simply confirms most climate finance experts’ fear that political considerations override disciplined scientific-based rationales. With global scrutiny on greenwashing, any coal-related investment will be unacceptable as green by ESG-focused investors even if it has phaseout or technical caveats.

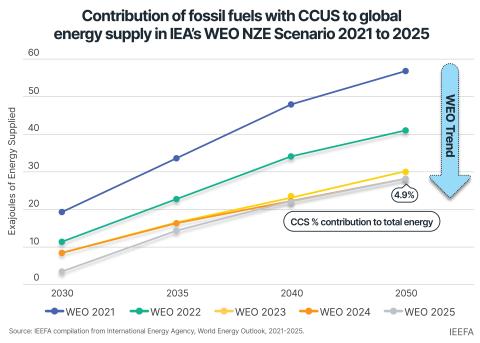

Another design flaw in the taxonomy is apparent in the commitment to apply more stringent criteria in the future TSC. To build credibility, ASEAN states that in the future, Tier 1 criteria will require power generation assets to have life-cycle emissions of below 100g of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour, comparable to the European Union taxonomy. The irony is that based on a 2014 study, virtually no CFPP would qualify, even with carbon capture and storage. If these transition coal assets will not be green in the future, how can they be considered green under the current TSC?

What is needed to create a credible taxonomy that would move the biggest ESG investors into Indonesia?

While Indonesia may have supported the ASEAN taxonomy, the Indonesian green taxonomy version 1.0 has appropriately put any coal-related activity in the Yellow and Red buckets. The country strictly earmarks the Green bucket for renewable energy, a plus for credibility of the taxonomy, although the usefulness of any taxonomy will rest on policy and market variables – many of which are still in flux given Indonesia’s multitrack JETP/ETM policy process.

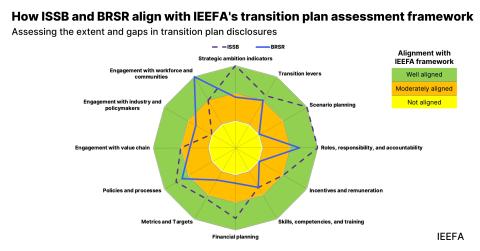

Generally, when stakeholders evaluate taxonomies and related disclosure standards, the challenges revolve around five issues: clarity of definitions, simplicity and ease of use of the taxonomy design, transparency and disclosure, interoperability and recognition, and access to verifiable data.

A few core principles can be considered for future updates to Indonesia’s Green Taxonomy when categorizing coal phaseout activities:

- Ensure green investments are genuinely backed by science and by not mixing the green activities or assets with the brown ones, even if they are intended to reduce emissions. Creating a new asset class that defines the activities or assets realistically would allow for a more genuine transition that would be appreciated by ESG-focused investors. In the case of the ASEAN taxonomy, keeping coal phaseout activities in the Amber bucket is more appropriate.

- Green labeling will be credible only when the definition is not just science-based, but also technically and financially viable in a specific market. This means separating the labeling process from political or business interests that can undermine the taxonomy by skewing the classifications and criteria.

- Defining the phaseout timeframe as a hard deadline is important, but so is using a credible and verified emission calculation as another key performance indicator. This calculation requires a credible baseline reference to avoid an inflated baseline scenario as the business-as-usual setting. The baseline in the ASEAN taxonomy should consider the plant’s capacity factor and merit order, instead of simply relying on the asset’s age or technology. An alternative could be to use emission monitoring systems, which many plants might not have.

- There are debt instruments in the market that are fit for financing coal retirement, such as sustainability-linked bonds or loans and tailored guarantee mechanisms. What is missing is a lack of clarity over what Indonesia considers transition activities. Clear definitions will help investors and financial institutions make strategic ESG-linked investments, while weaker taxonomy criteria will do nothing to help asset owners understand the environmental performance needed to mobilize capital to achieve each country’s climate target.

To get the most out of the JETP initiative, Indonesia’s policy planners would be smart to pay attention to ways that taxonomies can build credibility for investors who are willing to take on market risk to back ambitious decarbonization.

But taxonomies are only one part of the equation. Indonesia’s transition pathways have to be economically and socially feasible and follow an achievable timeframe. It can build investors’ confidence with a transparent and inclusive CIP planning process, one that is realistic about the needs of target investors and respects the needs of affected communities, and not just a small circle of political and business interests.