IEEFA US: Financial chaos in Powder River Basin coal country

The way America generates its electricity has been shifting away from coal for a decade, as the falling cost of wind, solar and gas have taken market share at an accelerating rate.

The way America generates its electricity has been shifting away from coal for a decade, as the falling cost of wind, solar and gas have taken market share at an accelerating rate.

The way the coal mining industry is structured, however, has changed very little, even as domestic consumption fell by more than 400 million tons, from 1.047 billion in 2007 to 637 million in 2018. Despite the ever-shrinking demand, the vast majority of U.S. coal production capacity has remained constant, even during a wave of bankruptcies that included Arch Coal and Peabody Energy in 2016.

The period of relatively orderly retreat appears to be over.

Major players have shown no interest in a just transition.

A wave of announcements in recent weeks indicates companies in the Powder River Basin are facing an unprecedented level of financial distress. Executives have made their priorities clear in a series of decisions that are playing out in damaging, unexpected, and chaotic ways for workers, state and local governments, communities and investors. None of the top brass at Westmoreland, Cloud Peak, Blackjewel, Arch or Peabody have shown a scintilla of interest in a just transition.

Recent developments of special note:

- Peabody Energy and Arch Coal, the first- and second-largest coal producers in the U.S., and owners of the two most productive mine complexes in the Powder River Basin, proposed combining their PRB and Colorado assets in a cost-cutting joint venture. The resulting entity would control over 60 percent of all PRB production—198 million tons, based on 2018 output. This move raises a hard question: How deeply dire is the situation if the vast economies of scale at the country’s two biggest mines cannot make money? The sheer size of the deal also raises serious antitrust issues, especially now that the future of several other producers is in doubt.

- The timing of Arch and Peabody’s announcement was significant, coming as it did just weeks before the three PRB mines of bankrupt producer Cloud Peak, the fourth-largest in the U.S., go up for auction. Potential bidders on at least some of those assets may now hesitate to invest rather than find themselves in a situation facing such a big, lean competitor. Those three mines on the auction block—Spring Creek, Cordero Rojo and Antelope Coal—produced 50 million tons in 2018.

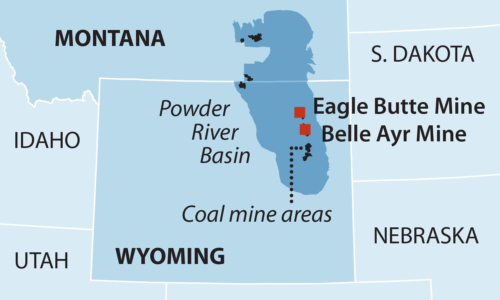

- Blackjewel’s sudden bankruptcy announcement on July 1— the sixth-largest U.S. coal company—and the possibly temporary but still unexpected closure of its two PRB mines, including the layoff of nearly 600 workers, after financing problems. The Eagle Butte and Belle Ayr mines produced nearly 36 million tons in 2018. In December 2017, Blackjewel picked up the two mines for deferred compensation of up to $50 million from Contura Energy; the bankruptcy almost certainly eliminates Blackjewel as a possible bidder for Cloud Peak’s mines, further diminishing the circle of potential buyers.

- The unexpected announcement that Colstrip units 1 and 2, in Montana, would close by December 2019, three-and-a-half years earlier than planned. Those units use coal from Westmoreland Coal’s Rosebud mine right next to the plant in the northern PRB. Talen Energy, Colstrip’s operator, said it was unable to reach a pricing agreement that would make the units economical. Westmoreland, which was the 10th-largest U.S. coal producer in 2018, only just emerged from its bankruptcy in March after failing to find buyers for most of its coal assets.

All four developments above underscore how bad the coal industry’s outlook has become in a trend that can be distilled into four points:

- There are fewer and fewer buyers for coal mine assets (see the Westmoreland example).

- It is all but impossible to profitably run mines even when picked up as distressed assets (see Blackjewel).

- Even economies of scale at the largest mines cannot make them competitive, not just with other coal miners, but with renewables and gas (see Peabody and Arch),

- Utilities with economically marginal or uneconomic coal-fired units, even next to coal mines, see shutting the units down as more viable than overpaying for coal (see Talen and Colstrip).

MEANWHILE, GOVERNMENT LACK OF PREPAREDNESS IS LEAVING WORKERS AND COMMUNITIES STRANDED—even despite ample warning of the decline of the coal industry. The federal government, and many state governments, have done little to support and protect mine and plant workers and their communities during this fast-moving transition. Instead, they are left to deal with the financial crisis that comes from lost jobs, lost retirement and health benefits, lost tax and royalty payments and falling property values after a lifetime of honest work.

Blackjewel’s sudden layoff this week of miners at the Eagle Butte and Belle Ayr mines—workers who may yet be recalled if Blackjewel can quickly work out its financing—appears to have left the state and local governments scrambling to respond, and workers may be owed retirement and other benefits that have gone unpaid in recent weeks.

And the financial damage spreads to the tax bases of the communities where the mines are located, impairing their ability to deliver needed social services. Blackjewel owes Campbell County, Wyoming, $37 million in taxes according to a list of the largest unsecured creditors; it owes the State of Wyoming nearly $12 million; and it owes the federal government over $72 million in royalties and taxes. Just one local machinery business in Casper, among a long list of creditors, is owed nearly $6 million.

Retirees have also lost benefits in the Westmoreland and Cloud Peak bankruptcies, affecting both the lives of these people and the communities where they would have spent those benefits.

NOT TO BE OVERLOOKED, THERE IS THE POTENTIAL DISRUPTION TO UTILITIES, a case in point being those affected by the closure of Blackjewel’s mines—should those mines remain closed for more than a few days. At least nine plants took delivery of more than one million tons from the company’s PRB mines last year and a scramble for replacement coal by these plants may happen at a high-demand time. To be sure, any unexpected purchases could mean a windfall for other PRB producers, but such unplanned purchases could add significantly to the plants’ costs, making them less competitive and profitable at a critical financial time of year.

Further, this sudden and disruptive event will erode the trust of utilities in future purchases of coal from financially weak mining companies, including from Blackjewel in any emergence from bankruptcy.

Top purchasers of coal from the Eagle Butte and Belle Ayr mines last year (in tons) included:

| Jeffery Energy Center, Kansas | 5,485,005 |

| Comanche Generating Station, Colorado | 2,456,681 |

| Plant Scherer, Georgia | 2,332,222 |

| Limestone Generating Station, Texas | 1,726,310 |

| Gentleman Station, Nebraska | 1,652,036 |

| Columbia Energy Center, Wisconsin | 1,490,626 |

| Gerald Fayette Power Project, Texas | 1,415,352 |

| W.A. Parish Generation Station, Texas | 1,070,367 |

| Baldwin Energy Complex, Illinois | 1,043,084 |

| White Bluff Power Plant, Arkansas | 992,132 |

Market restructuring will continue to roil the coal industry in the Powder River Basin. As it does, the list of companies that have behaved with crass irresponsibility to their workers and communities will likely, unfortunately, grow longer. The hardworking people of the region deserve far better.

Seth Feaster ([email protected]) is an IEEFA data analyst.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA U.S.: Renewables will likely outpace coal for the entire second quarter of 2019

IEEFA update: Out-to-pasture coal plants are being repurposed into new economic endeavors

IEEFA report: Powder River Basin coal industry is in long-term decline