IEEFA Update: G7 coal finance exit and why it matters for India

The commitment by the Group of Seven (G7) nations, along with several other European Union nations, to stop international financing of coal power projects by the end of this year is another strong step towards putting the world on a path to limit global warming to 1.5-2.0°C.

The agreement follows the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Net Zero by 2050 roadmap that recommends the world not develop any new unabated fossil fuel projects.

This coal ban by leading export credit agencies (ECA) builds on now 171 public and private banks, insurers and asset managers with formal exclusion policies relating to coal lending, investment and/or insurance policies, with 47 new or improved coal exit announcements in 2021 year-to-date, a rate of announcements 57% faster than during 2020, which in turn saw a 61% increase year-on-year compared to 2019.

These very positive global developments will have only a limited direct impact on India’s energy financing policy, given India does not rely on export credit agencies for new domestic coal plant financing.

The message that ‘coal is on the way out’ should not be underestimated

However, the overarching message of both the G7 announcement and the IEA roadmap is that “coal is on the way out”. This should not be underestimated.

In fact, we at IEEFA would say that these policy moves are both necessary and entirely compatible with the Indian government’s objectives of making India self-reliant in energy by cutting dependence on fossil fuel imports through its strategies of electrifying everything while concurrently driving towards 450 gigawatts (GW) of renewables capacity by 2030.

New solar in India is cheaper than running coal-fired power plants

New coal power plants in India are increasingly unbankable and unviable, unable to compete with the ongoing cost reductions clearly evident in the solar sector. This does beg the question of why the Government of India continues to try to open up yet more coal blocks for privatisation when the financial markets are heading in the other direction, aligned with the accelerating deployment of low-cost, domestic renewable energy.

The Indian government lauded the first round of private coal deposit auctions late last year as likely to attract significant domestic and global investor interest, including the likes of Rio Tinto, BHP and Peabody.

But the timing of the auctions coincided with the accelerated ambitions of the net zero emissions commitments from China, Japan and South Korea and followed climate pledges by some of the mining, utility and corporate giants, and the Indian government failed to grasp the implications of these global moves.

Rio Tinto sold its last mine in 2018, having started to exit coal in 2014. BHP put its last two thermal coal mines – Mt Arthur in NSW and Cerrejon in Colombia – on the market in 2020, but there was zero interest. Peabody is not interested in investing in Indian coal – its core U.S. market volumes collapsed >30% in 2020 and it is heading for its second bankruptcy.

There were no international bids in the first round, and the second round will garner a similar disinterest from offshore. Domestic interest may still opportunistically remain, given Coal India Ltd has regularly used its monopoly position to prioritise coal to its preferred customers, namely NTPC and the state distribution companies (discoms), leaving private firms struggling to power their factories due to the periodic unavailability of coal.

Although coal is set to remain the country’s dominant source of electricity for years to come, both the IEA and IEEFA see coal-fired power capacity in India peaking before 2025, consistent with the policy and economic statements of the major players in this sector.

IEEFA notes that in 2019 the then largest private coal-fired power company in India – Tata Power – announced it would no longer build any new coal plants, pivoting into lower cost, domestic, zero emissions renewable energy infrastructure.

In 2020 NTPC announced it would cease procuring land for new coal-fired power plants beyond those already under construction. NTPC acknowledges the least cost source of new supply is renewable energy, supported for firming capacity by India’s significant hydroelectricity capacity.

IEEFA expects India’s coal-fired power capacity to peak at 220-230GW by 2025

IEEFA expects India’s coal-fired power capacity to peak at 220-230GW by 2025, with long-delayed commissioning of under-construction plants being increasingly offset by end-of-life closures – a trend that is expected to accelerate beyond 2025 as expensive power purchase agreements (PPA) expire.

Critical to this is a step change up in construction of renewable energy infrastructure assets, which are clearly the lowest cost source of new generation capacity, but which have been heavily impacted by the demand crunch in Indian electricity over the two years to 2020/21, first by the growth recession then by COVID-19. Discoms have to-date largely failed to sign power sale agreements (PSA) in support of the government’s Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) series of very cost-competitive PPA auctions, a clear reflection of the lack of electricity demand growth.

A key factor in the unstoppable rise of solar power is the growing unviability of new non-minemouth coal fired power plants, particularly those reliant on imported coal.

But the global trend in coal divestment/exclusion policies means that new coal plants in India are also increasingly unbankable, even if they were to get PPAs to under-pin commerciality at face value.

With solar tariffs in India now consistently trading at Rs2-2.50/kWh, this is below even the coal fuel costs of running most existing domestic coal fired power plants.

India needs flexible peaking power to balance low cost, zero emissions but intermittent renewable energy – coal plants are ineffective for this purpose, slow to ramp and costly to run for short time frames.

Batteries are expected to be the key firming technology deployed in India within the next 3-5 years

Indian power firms are closely watching the booming battery markets of the U.S., UK and Australia, with this expected to be the key firming technology deployed in India within the next 3-5 years.

US battery installs in the fourth quarter of 2020 were a record of over 2.1GWh in total, growth of 182% quarter-on-quarter relative to the third quarter 2020, which was itself a record high.

Global finance corrects course to net zero emissions world

The IEA’s roadmap and the commitment by the G7 to end international financing for new coal power plants shows the world is increasingly serious about meeting the Paris Agreement goals.

Until 2021, the global financial markets had largely assumed the world would collectively fail to limit global warming – but now the financial markets are increasingly pricing in this eventuality.

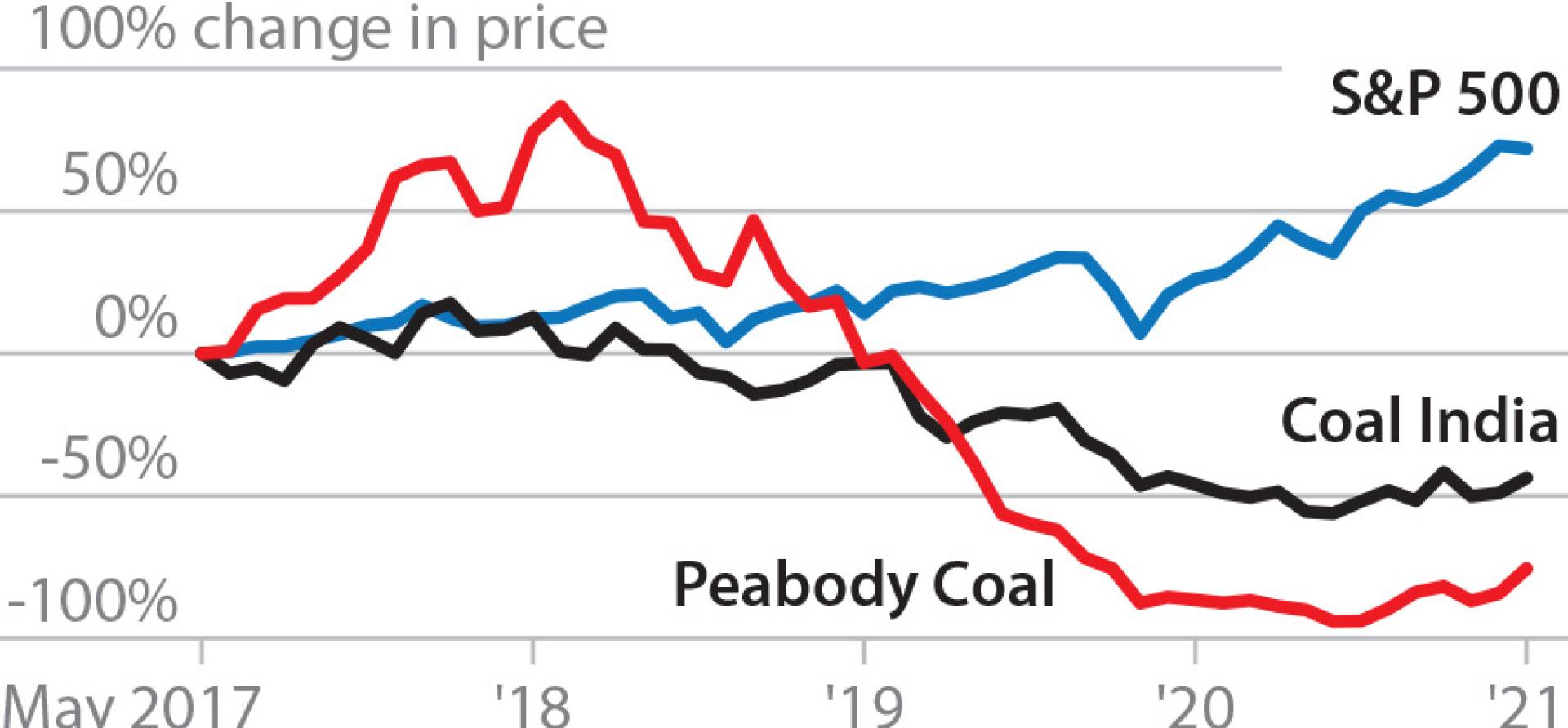

The clearest example of this is the 78% collapse in Peabody Energy’s share price since it came out of bankruptcy for the first time. The halving of Coal India Ltd’s share price in the same timeframe shows that global and domestic Indian investors are seeing a similar trajectory for India, albeit less dramatic. But a 48% decline in a period the global equity markets have been strongly rallying shows coal is on the way to terminal decline.

India needs to maximise the value extraction from its existing coal fleet, building a stronger price signal to incentivise flexible peaking power supply in support of ever more low cost, zero emissions, domestic variable renewable energy.

India also needs a clear long-term transition plan for its very significant and still valuable coal sector, not least to protect the 275,000 workers at Coal India, along with a similar number employed by Indian Railways and even more at the 209GW of coal-fired power plants across the country.

Tim Buckley is IEEFA’s Director Energy Finance Studies, Australasia

Related items: