IEEFA report: Seven disruptions driving the modernization of electricity generation and transmission

We’ve published a research brief today that looks at the underlying forces driving a global shift in how electricity is generated.

Our paper—“The Seven Technology Disruptions Driving the Global Energy Transition”—is a primer on fundamental changes occurring now that are collectively displacing coal from its long-dominant role in power generation.

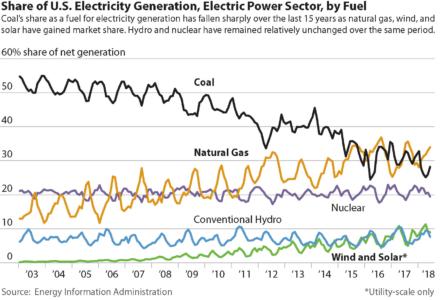

We note in the brief that coal is being rapidly replaced by natural gas, wind and solar as a worldwide push for electricity modernization intensifies.

Meanwhile, economic growth in many nations is no longer tied to increases in the consumption of fuel, as energy efficiency has grown and as the sectors leading economic expansions are less energy intensive than the heavy industries of the past.

And the “electrification of everything,” by which electricity—rather than other forms of energy—is powering more and more aspects of commercial, industrial, and consumer life is a trend that is most obvious in transportation, where the impact of electric vehicles is still small but is on course to completely transform the sector in the years ahead.

We break our seven core disruptions into four that are being propelled by generation-side activity and four that are grid-based. The report focuses mainly on how these changes are being felt in the U.S.

The four generation-side disruptions:

- Energy efficiency, which we term the “quiet disruption,” but one that can be seen in the growing disconnect between GDP growth and energy use even during the past decade or so of significant global economic expansion.

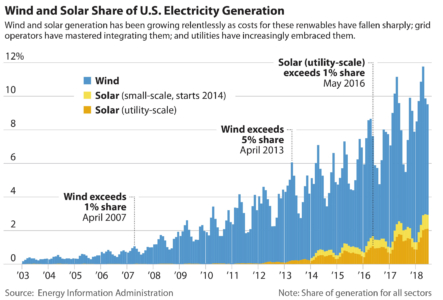

- The wind industry, a disruption that is seen most obviously in the U.S. across the windy Great Plains.

- The solar industry, which remains in a nascent stage compared to wind but that has seen a doubling in its utility-scale market share of U.S. generation, to 2 percent, in just the past two years; accounts for a 3 percent share including residential solar, and is set to continue growing fast as costs fall.

- The natural-gas fracking revolution, which alongside the rise of solar and wind has driven down the price of electricity generation.

The three grid-based disruptions:

- Grid integration, which has allowed for the seamless integration of thousands of utility-scale wind and solar plants across the U.S. and has meant a far higher market share for renewables than was forecast even a few years ago and facilitated greater flexibility in fuel switching by utilities.

- Grid independence, as individual consumers and businesses have rapidly developed the ability to either generate their own power or reduce their use by adopting technology that is driving their costs down.

- Storage, which—like solar—is in its early stages of uptake but that promises to make huge gains across the electricity industry as it brings a myriad of benefits to the entire electric-market ecosystem, including time-shifting of variable renewable generation, support for grid resilience and stability, the elimination of expensive “peaker” power plants, and—in the long term—the broad electrification of vehicles.

We note also that the above seven disruptions carry serious implications for the coal industry, which faces an increasingly bleak outlook as the electricity sector modernizes.

Taken together, these disruptions signal a permanent structural decline for coal in the U.S.

They indicate a future in which no new coal plants will be built the U.S., and retirements among the existing and aging coal power fleet will continue unabated. A restructuring of the coal mining industry is inevitable in the face of a shrinking customer base, massive overcapacity, and intense competition.

A subtler interplay of market forces will also continue to shape the energy transition in the U.S., that is, levels of cross ownership between coal companies and utilities. Most coal mining companies do not own stakes in power producers, and most power producers do not own stakes in coal companies.

This reality simplifies utilities’ economic decisions around closing coal plants—if a plant cannot turn a profit using coal, it only makes sense to shut it down and switch to a cheaper form of power production. On the other side, though, coal companies have little recourse beyond turning to a limited and fickle export market, because domestic use of coal for industrial, commercial, and residential purposes is disappearing.

More bad news for coal is rooted in the way utilities have already cut their coal-fired generation capacity. Most coal-fired units retired in recent years were among the smallest and oldest in operation. But because the energy transition is happening so fast, as costs for renewables and natural gas keep falling, some of the biggest plants have now become uncompetitive, and larger closures will almost certainly be more disruptive to the coal industry.

Seth Feaster is an IEEFA data analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA update: Another Texas coal-plant closing, another market signal