IEEFA: India’s technology path key to global steel decarbonisation

Recent announcements by global steel companies in India highlight how important the nation’s steel technology path will be to achieving global decarbonisation of the steel sector.

POSCO is planning US$5 billion of investment with Adani

ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel India (AM/NS) – a joint venture of two of the world’s largest steel producers, Europe-based ArcelorMittal and Japan’s Nippon Steel – has announced a US$13 billion investment in a 24 million tonne per annum (mtpa) steel plant in Odisha and a further US$22 billion investment in Gujarat. Meanwhile South Korean steel giant POSCO is planning US$5 billion of investment with Indian conglomerate Adani to build an integrated steel mill in Gujarat.

The announcements have, to varying extents, promised the use of “green” steel technology without providing any details.

The world’s largest steel producer, China, may have already reached peak of production and therefore, steel-related carbon emissions will likely drop. While China produced 1 billion tons of crude steel during 2021, down 3% year on year, India, the world’s second largest steel producer, produced 118.1 Mt of crude steel, a 17.8% rise from 2020.

In 2020, 56% of India’s steel output was produced via electric furnaces from which less than half was attributed to electric arc furnaces and the rest was produced on induction furnaces. These furnaces are mostly fed with direct reduced iron (DRI). India has a high share of steel production based on DRI utilizing gasified thermal coal which produces more emissions than DRI based on natural gas. The balance of 44% was produced via blast furnace route, using coking coal. Indian steel demand growth has led to significant investment in new blast furnace capacity in recent years.

India’s steel sector has a higher energy intensity compared to the global average

Hence, the Indian iron and steel sector is the most significant contributor to industrial energy demand, with a high reliance on coal (85% of energy inputs). Currently the steel industry represents almost 23% of total energy inputs and 30% of the industrial carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the industrial sector.

The main reasons for the higher energy intensity of India’s steel sector compared to the global average include its high reliance on coal, lower share of scrap steel recycling, a fragmented and low performance casting sector, and the number of old blast furnaces.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) in its Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) predicted that India steel production will double by 2030 and quadruple by 2050. Coal demand is also forecasted to increase by 250%. Curbing CO2 emissions and meeting a growing steel demand seems to be a dilemma for policy and industry decision makers.

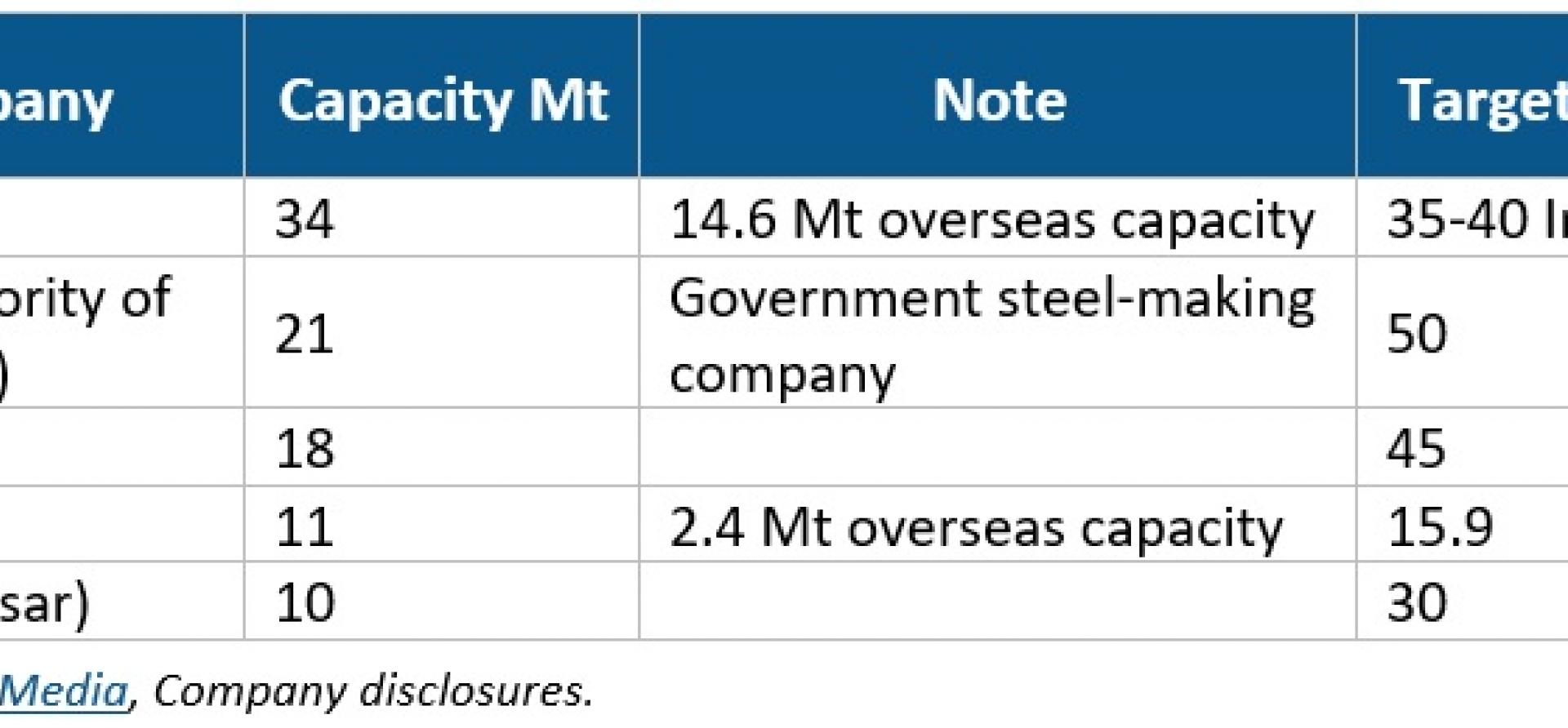

Tata steel, JSW, Steel Authority of India, Jindal and AM/NS are among the largest producers in India.

AM/NS’s new announcements represent a significant increase in its Indian steel capacity and will supposedly use green steelmaking technology at the Odisha plant. The US$22 billion to be invested in Gujarat involves a range of projects including 10 gigawatts (GW) of solar and wind development for the decarbonisation of steel production.

POSCO’s move will be its first new steelmaking investment in India after four unsuccessful attempts in the last 17 years.

The lack of steel technology detail in these announcements is in contrast to those made in developed nations whenever companies want to highlight their shift towards low carbon steel.

ArcelorMittal announced it was building a new DRI-EAF in its Spanish operation plant that could reduce carbon emission by 50%. In another agreement with the Government of Canada, ArcelorMittal will install DRI-EAF technology to phase out the current blast furnace and reduce emissions by 60%.

India faces a major challenge in decarbonising its coal-reliant steel industry

POSCO’s Memorandum of Understanding with Adani is part of its plan to set up “green” steel capacity outside of South Korea.

Investing in any new coal-based steel technology in the 2020s will lock-in carbon emissions for decades. Steel production assets are durable, and the average operational life of a blast furnace is up to 50 years. Investing in blast furnace technology in the 2020s means new plants would work even after 2070 which is the announced year for India to reach net zero emissions.

India’s fast-growing steel demand denotes that it faces a major challenge in decarbonising its coal-reliant steel industry. However, using low cost renewable electricity, India may have the opportunity to produce cost-competitive green hydrogen to use in the ironmaking process.

DRI can be produced using zero-emissions green hydrogen rather than gas or coal. The current drawback is its cost.

Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd’s huge planned pivot towards new energy technology has the potential to enable an era of cheap green hydrogen in India. Its planned US$75 billion of investment in renewable energy and electrolysers will help push down the cost of green hydrogen – the company is aiming for US$1/kg underpinned by 100GW of renewable energy, both before the end of this decade.

Reliance’s green hydrogen ambition is now being followed by others

Reliance’s green hydrogen ambition is now being followed by others including Adani.

The global steel industry is poised to shift from coal to hydrogen. With enough high-quality iron ore and low prices for hydrogen, India could play a pivotal role in global steel decarbonisation given its large and growing economy.

We await details of the technology intended to be used by AM/NS and POSCO/Adani –global steel decarbonisation will be difficult if low-carbon steel capacity is built in developed nations whilst older, carbon-intensive technology is built in developing nations where much of the steel demand growth can be expected.

By Soroush Basirat and Simon Nicholas, energy analysts, IEEFA

Related articles:

IEEFA: Blue Hydrogen Has Extremely Limited Future in U.S. Energy Market