Fortum-Uniper's bet on Europe gas dependence proves poor strategy

When Fortum, the Finnish state-owned energy company known for its Nordic hydro and nuclear power generation, launched its acquisition of Uniper—the German fossil-focused energy company spun out of E.ON—the transaction created one of the largest energy producers in Europe. The narrative since has been that the proverbial green knight Fortum would help Uniper clean up its act, and together they would become one of Europe’s leading clean energy companies.

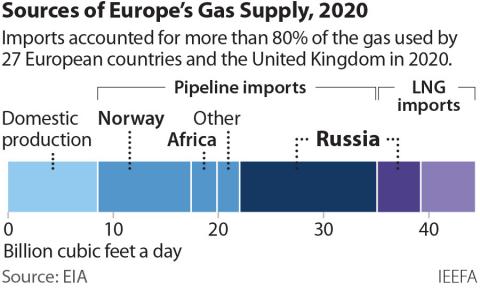

This vision was predicated on two pillars—a steady supply of cheap gas into Europe and ongoing operations in Russia—but the gas price crisis and Russian invasion of Ukraine have shaken the foundation of Fortum-Uniper’s business strategy. The immediate question is how the company will survive. It is clear that a radical change of strategy is needed, but in what direction?

It is clear that a radical change of strategy is needed, but in what direction?

Fortum used to be a major player in Nordic electricity distribution grids, which were largely served by nuclear and hydropower generation. In a bid to reduce debt and focus on power generation, it sold off those businesses earlier last decade for approximately €9 billion. By taking over Uniper, the company would be buying into fossil fuels and more than tripling its carbon footprint from energy production (e.g., from 19 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2019 to 69 million in 2021). However, it would also enter continental markets, expand its footprint in Russia and Sweden, and benefit from seemingly dependable fossil-based cash flows.

The takeover has not been straightforward. Uniper’s management was opposed to the deal. Four years later, Fortum still does not own 100% of Uniper’s shares. The Financial Times Lex Column reported in January that a buyout of Uniper’s remaining minority shareholders would cost more than €3 billion and leave little financial room for planned green investments.

A bad year for shareholders

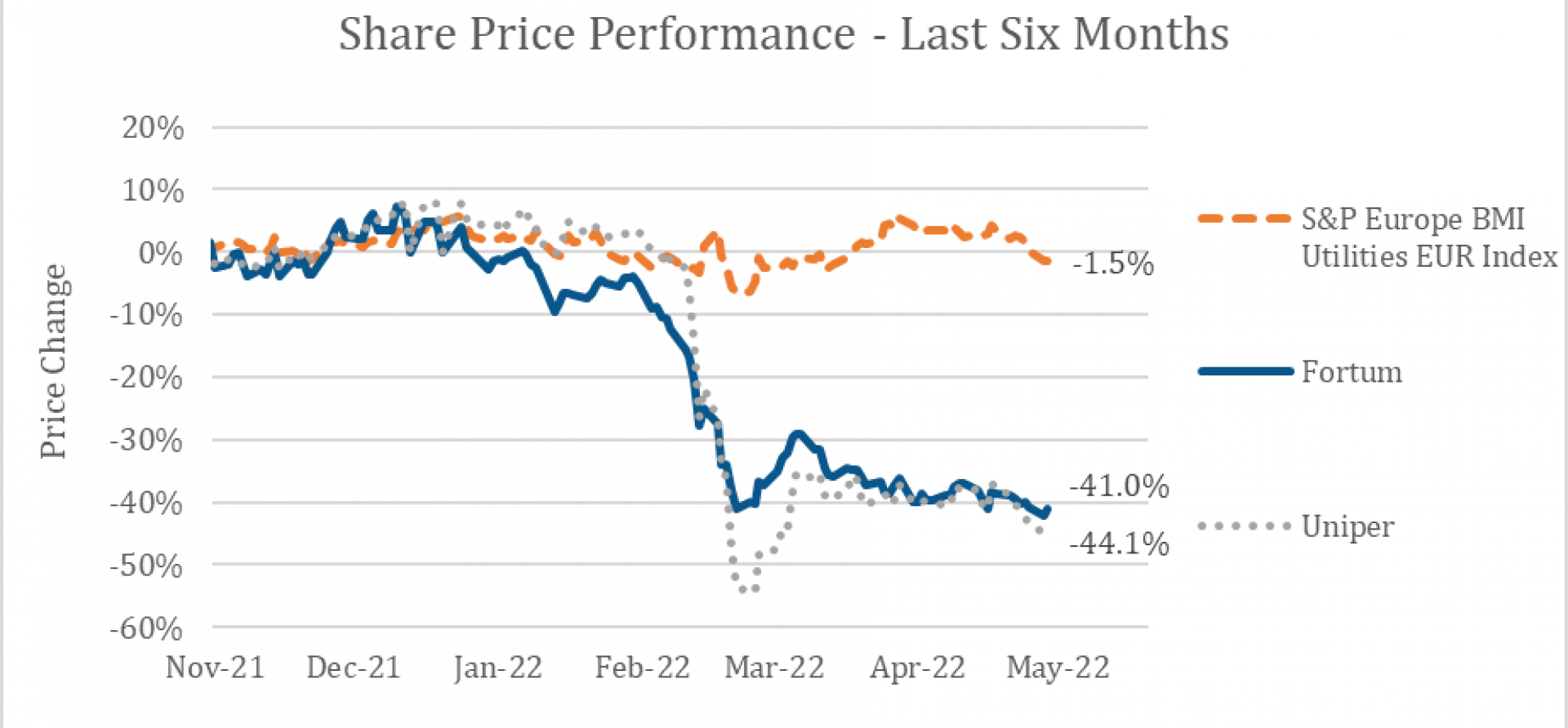

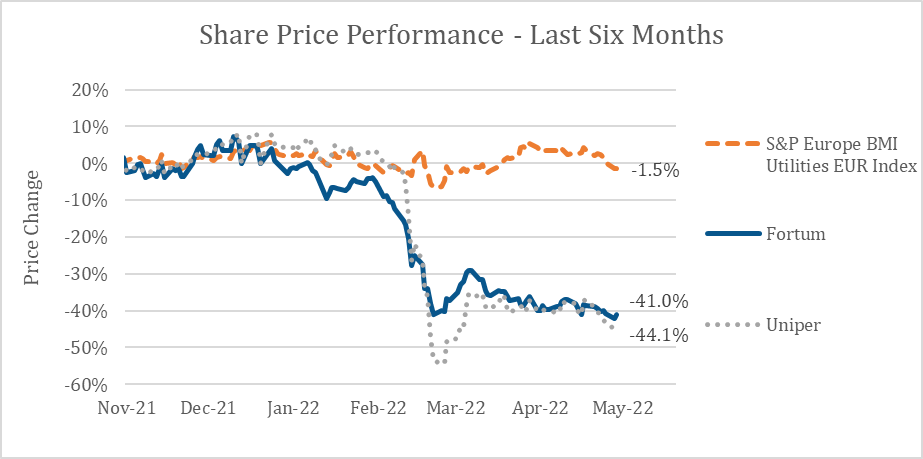

This year has been abysmal for Fortum-Uniper’s shareholders, with a slew of negative developments. In January, Uniper announced it had been forced to secure €8 billion of credit from Fortum and €2 billion from German state bank KfW to cover its hedging positions after high gas and electricity prices triggered demands for cash (known as margin calls). In February, Russia’s invasion caused retaliatory sanctions and swift depreciation of the Russian ruble, bringing uncertainty to Fortum’s operations in Russia.

Share prices of Fortum and Uniper have fallen sharply this year, down over 40% vs. six months ago

Source: S&P Market Intelligence, as of 6 May 2022

In March, Uniper announced it would slash its dividend by 95% for 2021 to preserve cash, paying out only €0.07 per share (compared to €1.37 per share in 2020). Fortum released a statement quantifying its book value exposure at €5.5 billion (via the stranded Nord Stream 2 pipeline project and its Russian operations), noting that its Russian operations contributed 20% of group earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) in 2021. The company stated that “business as usual cannot continue” and highlighted “Europe’s need for an urgent energy transition.” However, the statement provides scarce details about Fortum’s own energy transition, instead adopting a greenwashing narrative with vague and potentially misleading terms like “clean gas” and “hydrogen-ready.”

The same narrative is also prominent in Fortum’s responses to questions submitted for its annual general meeting. Meanwhile Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s (which currently give Fortum BBB and Baa2 ratings, respectively) have both put Fortum on Credit Watch Negative as they assess the implications for its credit rating. A downgrade of one notch would mean Fortum just keeps its investment-grade status (BBB-/Baa3 or higher), while any further slide would move the company into junk bond territory.

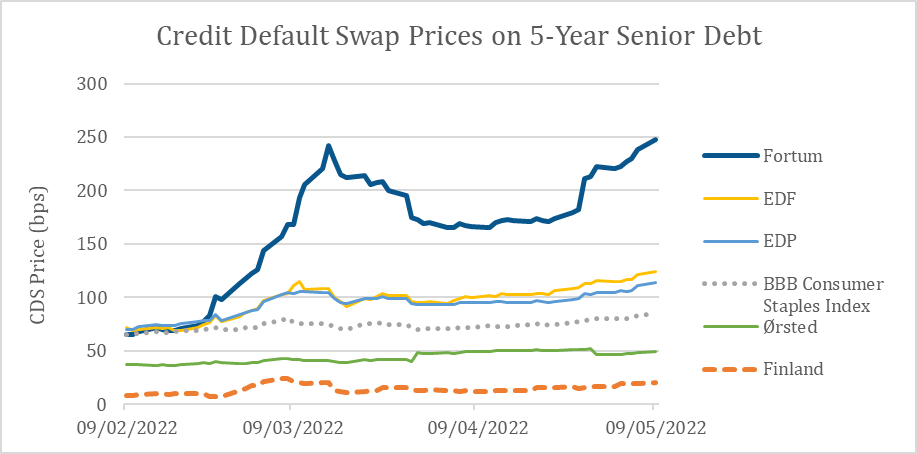

In late April, Uniper announced a profit warning for the first quarter of 2022 but insisted that guidance for the full year remains unchanged. The news renewed concerns about Fortum’s own financial position. Market spreads of credit default swaps (CDS) on Fortum’s five-year senior debt have widened since the invasion with its CDS currently trading at a price of about 230 basis points (bps), or 150bps above comparable BBB rated debt— implying a high perceived risk of downgrade.

Widened spreads on Fortum’s credit default swaps indicate high perceived risk of downgrade

Source: S&P Market Intelligence

For comparison, the same metric for France’s nuclear-heavy utility EDF and Portugal’s renewables-strong utility EDP, which are both also rated BBB, currently sits at only 35bps and 25bps above the same benchmark. Meanwhile, renewables-focused Ørsted (rated BBB+) is trading at a discount, 70bps below the benchmark.

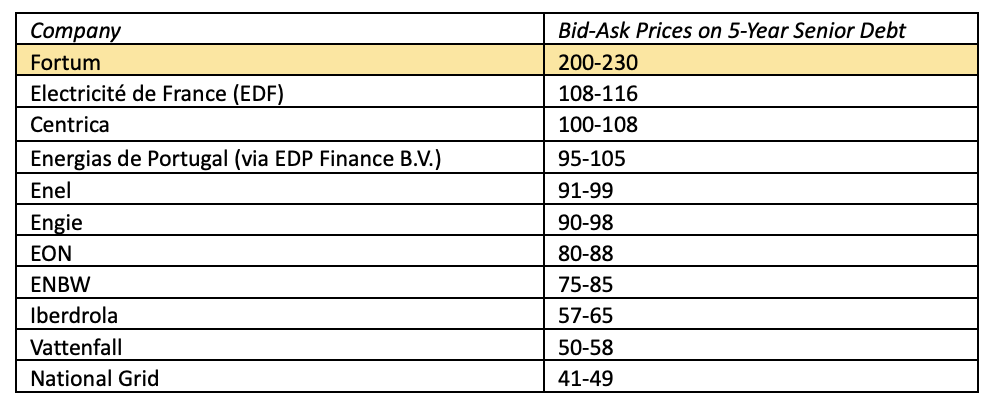

Fortum’s CDS spread is far higher than other European utilities

Source: Bloomberg, as of 6 May 2022.

As of May, Fortum’s financial situation has worsened. The company announced it will record pre-tax impairments of approximately €2.1 billion related to its Russian operations (including Uniper’s investment in Nord Stream 2) in its first quarter 2022 results, which are due to be released on Thursday.

Fortum’s statement confirmed that its net assets in Russia are now reduced to €3.3 billion (i.e., from the €5.5 billion of book value originally announced at risk). Over the same period, a Finnish consortium that includes Fortum announced it would cancel a new nuclear power plant in Finland, Hanhikivi 1, which had been planned with Russian state company Rosatom.

Fortum’s greenwashing and (lack of) long term energy transition strategy

Fortum has set targets to make its European power generation carbon neutral (or “net zero”) by 2035, and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by at least 50% by 2030 compared to 2019 (all Scope 1 & 2 emissions). There is also a longer-term target of complete group carbon neutrality by 2050 (Scope 1, 2 & 3). However, according to an analysis by the investor-led initiative CA100+, Fortum fully meets the required criteria in only two out of 10 benchmarking categories: For 2050 ambition, and for information disclosure.

The company only partially meets criteria in other categories and completely fails in arguably the most meaningful category of all: Capital alignment. In other words, according to CA100+, the company is not backing up its net-zero rhetoric with suitable investment plans.

Fortum’s investor presentation is flush with bold statements and claims regarding sustainability. For example: “Our purpose is to drive the change for a cleaner world. We are securing a fast and reliable transition to a carbon-neutral economy by providing customers and societies with clean energy and sustainable solutions. This way we deliver excellent shareholder value.” Is this really the case?

Fortum’s near-term reduction in carbon emissions will be driven by closing, exiting, or converting (to gas or biomas-firing) about 8 gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired power capacity in Europe by 2030. The company has not “driven change” on this issue—much the opposite. Its subsidiary Uniper entered a legal dispute with the Dutch government last year to challenge a coal exit law that would force the closure of its plant in Maasvlakte by 2030, seeking compensation for alleged lost profits beyond that date. In Germany Uniper pushed ahead with construction of its new Datteln 4 coal power plant despite widespread opposition and last year a German court ruled that building permission for the facility was granted illegally.

Exiting coal will not be enough to take Fortum to net zero. The company will also need to decarbonize or phase out its gas fleet and gas operations, but this phase of Fortum’s transition looks highly uncertain, risky, and expensive. The company’s decarbonisation strategy depends entirely on major technological innovations, advancement, and infrastructure buildout in areas such as large-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) and low-carbon hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and use. It is highly uncertain if or when hydrogen will be used instead of gas, and Fortum has refused to give any specific timeline commitments for switching out of gas in its power plants. Pointing to a pathway of gas-to-unknown conversion while avoiding timeline commitments does not constitute a solid plan and cannot be described as fast or reliable.

Despite the gas price crisis, uncertainty of supply following the invasion of Ukraine, and the need to accelerate the energy transition, Fortum is continuing to bet on a future of gas dependency in Europe.

In response to questions asked by shareholders during its AGM in Marchannual meeting, Fortum reiterated that “Fortum Group – and the German government – sees gas powered power stations crucial [in 2035] for the energy transition to keep up security of supply.” This is a contentious position. The Russian invasion has highlighted the very real security and pricing risks of having a gas-dependent energy system, and the energy mix of supply and demand is likely to look very different in 2035. Other gas-exporting countries are by no means immune from political instability and turmoil in the coming decades.

The best way to improve European energy security is to reduce its dependence on gas. Long-term planning should be prioritizing this shift, which requires action on both the supply- and demand-side. Instead Fortum has aligned with the European gas lobby to continue business as usual for as long as it can get away with it, while pushing false solutions like CCS and blue hydrogen. Quoting again from the company’s response to shareholder questions: “In principle we still consider blue and turquoise hydrogen to be sensible technologies on the way to a green hydrogen economy, but these gases are not feasible due to the current gas price development…”

Better ways forward

In comparison with its plans for coal and gas, Fortum’s renewables ambitions are tiny, with a stated aim to build just 1.5GW to 2GW of new capacity by 2025. Its target needs to be higher, with more in Europe. According to the latest investor presentation, Fortum plans only 0.4GW of projects in the Nordics, with 0.6GW in India and 1.4GW in Russia. For nuclear generation, Fortum has already announced an intended lifetime extension of its plant in Loviisa, from 2030 to 2050. Fortum also owns a 25% share in the the Olkiluoto 3 power plant—originally in construction since 2005 and more than a decade overdue—which is finally expected to begin regular generation at 25% capacity (0.4GW) this year.

Perhaps the most concerning part of Fortum’s plan is its likely reliance on carbon offsets, “we will not rule out also to use carbon-offsetting”. This is a massive cop-out. Carbon offset markets are unregulated with a huge range of prices and effectiveness, meaning that it is often closer to a payment-to-pollute than an actual time-matched offset of one’s emissions. Paying to pollute in this way does not drive change for a cleaner world. Instead, it gifts a life extension to business-as-usual activities.

Taking a step back and considering Fortum’s overall situation, a more holistic solution might be for Fortum to admit that Uniper was too big and bitter to digest and to separate itself out from the most toxic parts of that business that are currently weighing Fortum down financially, environmentally and strategically. For example, splitting out its gas storage and trading operations from its power and heat generation could be a start. If done correctly, this could reset valuations, improve access to capital, and decouple Fortum’s net-zero transition strategy from European gas dependence. Fortum urgently needs to do so if it wants to keep its investment-grade status and stay true to its climate commitments.