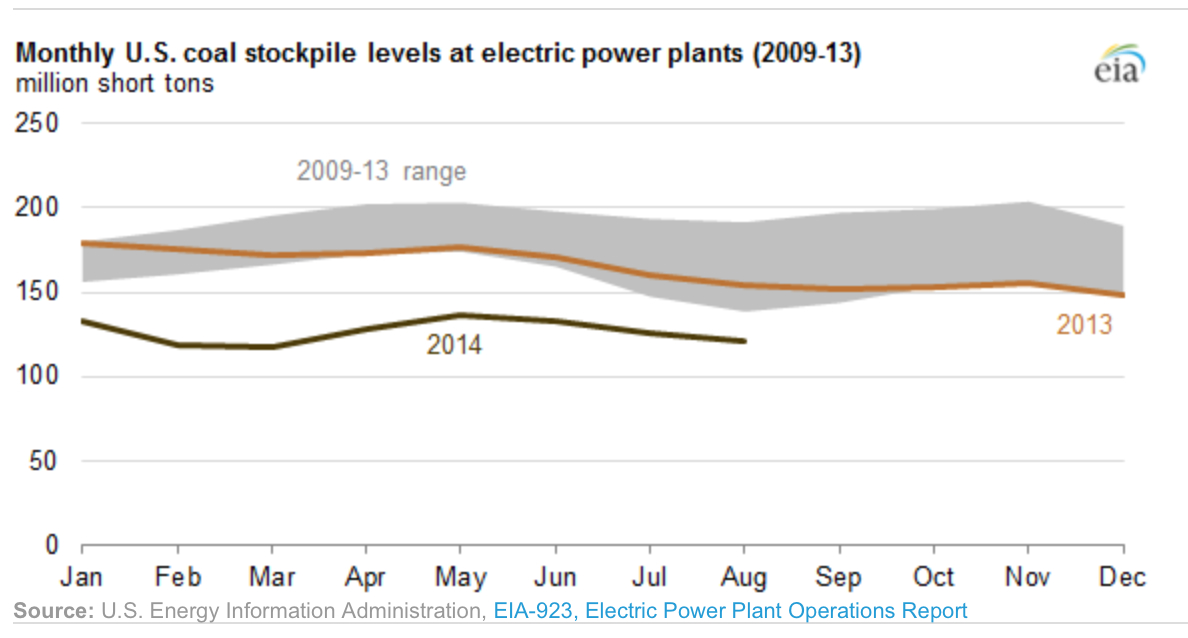

Time was that whenever U.S. utility-coal stockpiles shrank, stories would start circulating about how if the trend wasn’t reversed promptly, there would be hell to pay as the weather changed. Winter would hit and demand for coal-fired electricity would be off the charts as cold customers sought warmth. Alternately, summer would bring heat waves that would drive people to crank up their air-conditioners en masse.

Either way, coal stockpiles as a result would dwindle, according to this narrative, replenishments would not arrive in time, valuable coal would sit unmined, power plants would fall silent, and brownouts—or worse—would cripple the economy and endanger the country. You knew also (sigh) that when utility-coal stockpiles got low, solicitations for new orders would soar, prices would rise, train runs would increase, production would go up, and—voila!—coal-industry numbers across the board would rise.

Utility-coal stockpiles are down today, to be sure, but none of the usual stuff described above is happening. This break in the historical pattern has not gone unnoticed. For much of the past year, a small corp of coal analysts have noted perceptively that as utility-coal stockpiles have fallen, demand for new coal has stagnated. Platts Coal Trader, for one, has devoted considerable, informed coverage to the issue, which has helped raise an interesting question: If low stockpiles are a new norm and if new coal demand is just around the corner as many coal-industry executives say, why aren’t investors flocking back to coal stocks? The big-picture answer is that natural-gas prices have remained stubbornly low and that wind and solar energy are capturing the nation’s energy-investment dollars—and the public’s imagination.

But something else may be at work, too, as SNL Energy noted in an article last week suggesting that U.S. utility-coal stockpiles are so low today (see the chart above) because so much of the existing coal-fired utility fleet is poised for retirement and that the utilities that own those plants are burning down their coal stockpiles because they aren’t going to need them. The Sierra Club deserves mention for its work on this point, and the issue calls for more research and transparency, something in short supply from the coal industry.

The bottom line is that a structural change is going on in the energy finance markets. More and more coal-fired electricity plants will be retired as time goes by, and that means less and less demand for coal-fired electricity.

The coal industry, however, seems mired in denial, hewing to old habits and resisting diversification even as the energy economy changes, proceeding clearly and plainly with its shift toward renewables and cleaner fuels.

Another change that’s hard for anybody to ignore: Coal stocks are down 60 percent over the past three years while the Dow Jones Industrial average is up 60 percent. Like the recent disruption in the utility-coal stockpile routine, it’s a break in a deeply historical pattern. The U.S. economy and the coal industry have risen and fallen in tandem for decades. That’s no longer the case.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.