China is building a more credible green finance market but state-owned enterprises’ green bonds are in the way

Key Findings

As important as the announcement of China’s Green Bond Principles in July was, investors should remain cautious as not all onshore green bonds play by the same rules.

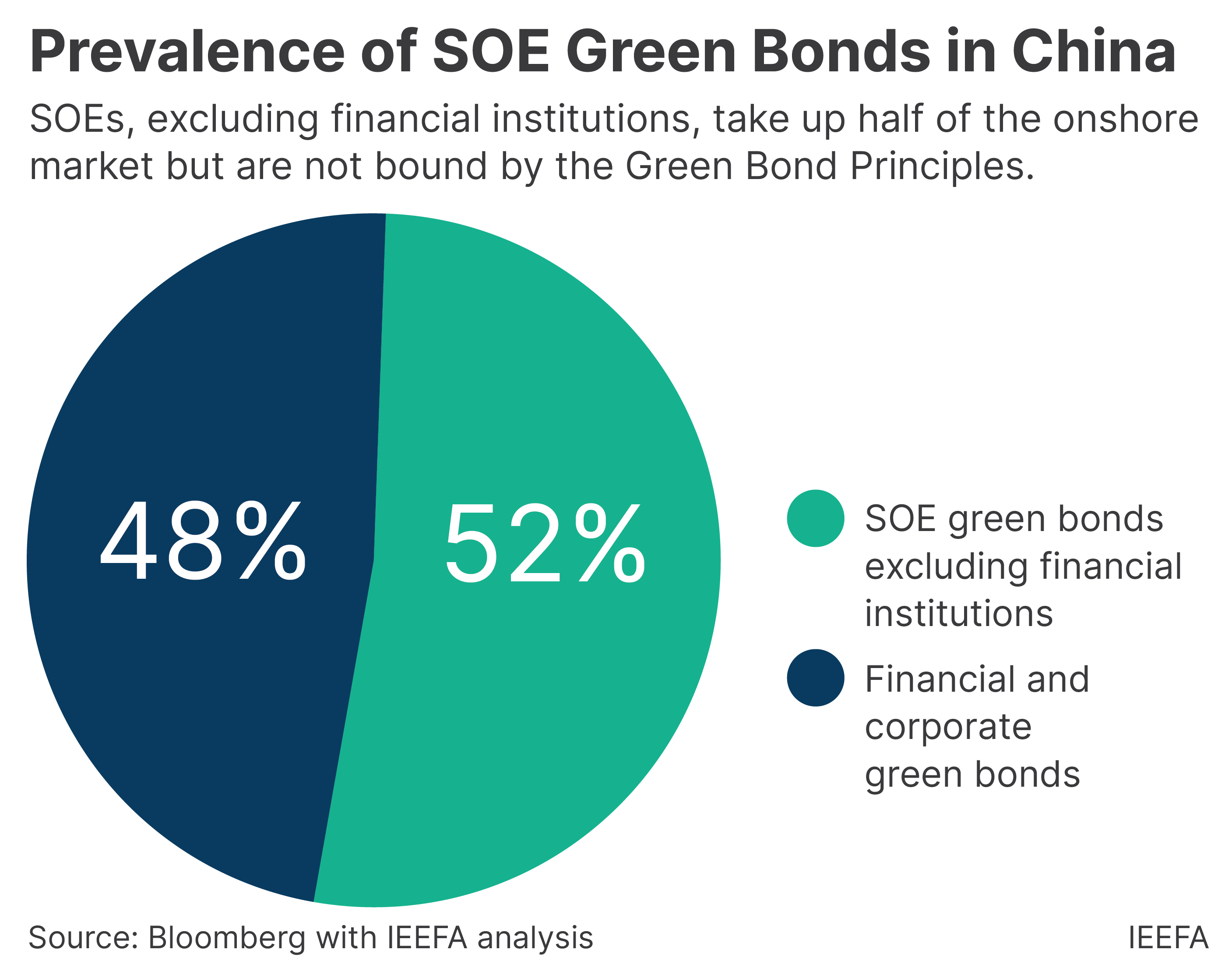

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) accounted for about half the onshore green issuances from 2019 to 2022. However, enterprise green bonds, which are issued by state-owned enterprises, have yet to apply the Green Bond Principles.

Investors should continue to be wary of SOEs’ onshore green bonds in the absence of the backing by National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of the Green Bond Principles.

China’s ambition to green its financial market has been making significant progress. Chief among the efforts was the publication of China’s Green Bond Principles in July 2022.

The new rules are said to closely align with international green bond standards and to unify the formerly fragmented domestic market. A key amendment requires 100% of the proceeds to fund green projects, instead of 50-70% previously.

This is a big step for foreign investors who are eager to invest in China’s domestic green bond market but have concerns about greenwashing—inadvertently buying ‘green’ bonds that, in fact, support non-green projects.

As important as the July announcement was, investors should remain cautious as, on closer examination, not all onshore green bonds play by the same rules. Enterprise green bonds, issued by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), have yet to apply the Green Bond Principles. SOEs accounted for about half the onshore green issuances from 2019 to 2022.

Significant steps to green Chinese financial market

The rollout of the Green Bond Principles is one in a series of efforts by China to build confidence in the market and develop sustainable finance domestically.

In 2021, China’s Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue—its green taxonomy—officially removed ‘clean coal’ and fossil-powered generation, including gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG), from the definition of ‘eligible green project’. This was markedly different from the Green Taxonomy of the European Union (EU), which classified gas as a sustainable investment.

Later that year, China and the EU jointly compared their respective taxonomies to identify commonalities and differences, resulting in a Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT). The CGT does not have a legal effect and is not formally endorsed by either party. However, it offers capital providers certainty about which kinds of assets would be accepted as green investments in both regions.

This year, China introduced the Green Bond Principles, which closely follow green finance guidelines that have been established by the International Capital Market Association and the Climate Bonds Initiative and are accepted as the reference standard worldwide.

In addition, new green bonds issued in China must now better align their disclosures with international markets. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) is pleased to see these new requirements, which are largely consistent with our recommendations on improving the governance of Chinese green bonds.

Loophole in SOE green finance

Notwithstanding the progress made, a compliance gap remains as the governance of China’s green bond market is fragmented. No fewer than four regulatory bodies, each with its own set of rules, oversee the different types of bonds. These regulators are the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII) and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

IEEFA released a report in June 2021 highlighting a significant loophole in the regulations. The report noted how certain sectors were allowed to allocate proceeds received on their green bond issuances to working capital to fund day-to-day operations that were not necessarily green or to finance existing debt.

In the report, IEEFA urged regulators to tighten the rules to make all sectors fully channel their green bond proceeds to eligible green projects. The Green Bond Principles did just that a year later, in July 2022. Since then, the PBOC, CSRC and NAFMII have required all financial, corporate and non-financial corporate bond issuers, respectively, to comply with the new rules.

However, it appears that the NDRC, which oversees enterprise bonds, has yet to mandate SOE adoption of the Green Bond Principles.

As such, SOEs continue to be permitted to allocate up to half of their green bond proceeds to non-green projects. Their green bonds are also exempted from a need to account for the use of the proceeds, environmental impact monitoring and reporting, or verification before and after the issuance.

This is problematic for investors. SOEs, including coal-dominated power producers China Huaneng Group, China Huadian Corporation and State Power Investment Corporation, are regular green bond issuers with a growing pipeline of coal projects despite also having big plans for clean energy. Without stricter rules on the use of proceeds and project verification, it is not inconceivable that the funds could go toward maintaining a steady, or more likely growing, coal business, which effectively spells greenwashing.

What does this mean?

China’s green bond market will remain fragmented, albeit to a lesser extent, until the NDRC mandates SOEs to comply with the Green Bond Principles.

Foreign investors of green bonds are alert to the risk of greenwashing and reluctant to support issuers that lack transparency. They want certainty that they are funding clean and sustainable technologies.

While many Chinese green bonds are expected to become more aligned with international markets, investors should continue to be wary of SOEs’ onshore green bonds in the absence of the NDRC’s backing of the Green Bond Principles.

The Chinese-language version of this commentary is available here.