Key Findings

Canadian LNG exporters aim to sell gas to Japan, which has emphasized the need for more LNG to provide energy security.

Even though Japanese LNG demand has fallen, Japan is still buying gas in hopes of reselling to South and Southeast Asian markets.

Japan’s push for Canadian LNG is more about cementing gas expansion opportunities rather than ensuring domestic energy security.

Exporters claim Canadian LNG will replace coal in Asia, but evidence from the largest coal-consuming countries suggests otherwise.

With LNG Canada set to start up next year, liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporters in Canada are racing to build new projects along the country’s western coast. Many are enamored by the prospect of selling the fuel to Asian countries, particularly Japan.

As one of the world’s largest LNG buyers, Japan has repeatedly emphasized the importance of Canadian LNG for its energy security, decarbonization, and reducing reliance on Russian energy. In a January 2023 visit to Ottawa, former Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida stressed the “crucial role” of Canadian LNG in Japan’s energy transition.

Kishida, however, failed to mention that Japan’s LNG imports have fallen every year since 2014. Over the last decade, the country’s LNG demand has dropped by 25%, and its official energy plans envision it falling by an additional 25% to 2030, due to rising nuclear power and renewables replacing the need for gas, among other factors.

Why, then, is Japan pressuring countries like Canada—as well as the United States, Australia, and other exporters—to ramp up production?

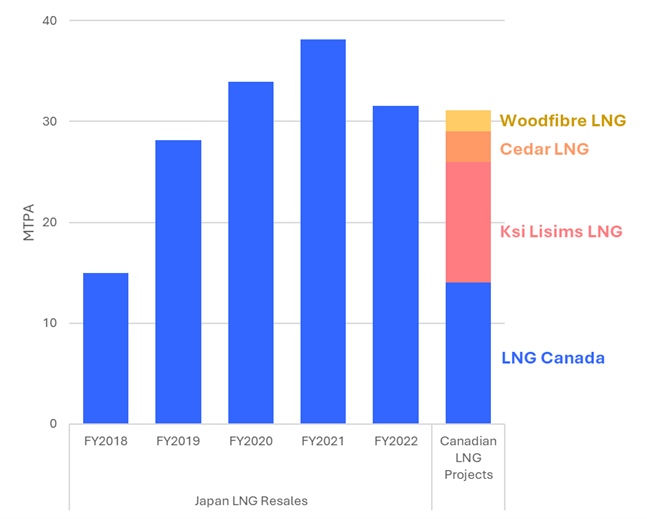

One potential reason is that Japanese buyers of LNG are re-selling the fuel into other markets at a markup, rather than sending it directly to Japan. In FY2022 (the most recent year for which data is available), Japan resold almost 32 million tonnes of LNG to other countries, according to official data.

For perspective, this resales volume far exceeds the annual export capacity of the three Canadian LNG projects that have made final investment decisions and are undergoing construction—namely, Canada LNG, Woodfibre LNG, and Cedar LNG—with a combined output of 19 million tonnes per annum (MTPA). Japan’s resales still exceed potential Canadian LNG export capacity when including another major proposed project, the 12 MTPA Ksi Lisims LNG facility.

Figure 1: Japan’s LNG Resales vs. Canadian LNG Projects

Source: JOGMEC, media reports.

Consider two of the largest LNG buyers in the world, Japan’s JERA and Tokyo Gas, which have both agreed to buy volumes from the Canada LNG project. An Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) report released this year found that both companies are likely to have a surplus of LNG supplies through 2030 to resell. And both have expressed intentions to pivot business growth toward LNG expansion in markets outside of Japan, due to declining domestic opportunities.

The Japanese government, meanwhile, is playing a key role by lobbying foreign governments to increase LNG exports, while setting resale targets for domestic companies. In 2020, the country’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry set a target for Japanese buyers to transact 100 MTPA of LNG by 2030, well above the country’s own projected demand.

As a result, these companies are actively seeking opportunities to resell LNG to other Asian markets. Japanese players have proposed at least 30 gas and LNG-related projects in South and Southeast Asia, which may come with commitments to buy LNG from Japanese project sponsors.

It’s clear that Japan’s push for Canadian LNG is more about cementing future business expansion opportunities rather than domestic energy security. This strategy threatens to lock in fossil fuel infrastructure in Asia for decades, rather than facilitate the region’s clean energy transition.

Of course, this all runs counter to claims by the Canadian LNG advocates, who often argue that without energy supplies from like-minded allies like Canada, Japan will be forced to rely on Russia or Qatar. However, Japan’s combined imports from both countries have fallen 65% since 2013 without any Canadian LNG.

These aren’t the only claims that fail to stand up to reality. LNG industry representatives often tout the role that Canadian gas exports can play in reducing Asia’s emissions by displacing coal-fired power. They typically point to China and India—the two largest coal-consuming countries in the world—as examples for where LNG can have the largest climate benefits.

But neither China nor India is using LNG to replace coal. In China, the share of gas in electricity generation has remained at just 3% over the last decade, while the share of wind and solar has quadrupled to 16%. In India, the share of gas has fallen to less than 3% over the same period, while the share of wind and solar has tripled to 10%.

Renewable energy—not gas or LNG—is providing the biggest competition for coal in both countries, due largely to cost and energy security incentives. For example, China has issued policies to “strictly control” coal-to-gas switching and cap reliance on imported gas, while deploying renewables at an unprecedented scale.

This sets up a challenging business case for Canadian LNG expansion. Over the next four years, global LNG export capacity is on pace for the largest increase in the industry’s history, while countries in Europe and Northeast Asia cut demand. This looming supply glut could ultimately cause revenues to fall for LNG sellers.

Moreover, Japanese buyers could exacerbate oversupply by re-selling LNG on the global market rather than consuming the fuel themselves.

Instead of building out LNG infrastructure under the guise of energy security and decarbonization, Canadian policymakers can support renewable energy growth through diplomatic channels, like the G7. Ultimately, Canada should use its geopolitical influence to promote real climate solutions, not the expansion of Japanese gas interests throughout Asia.