Australia’s decommissioning challenge raises financial risks for governments and shareholders

Key Findings

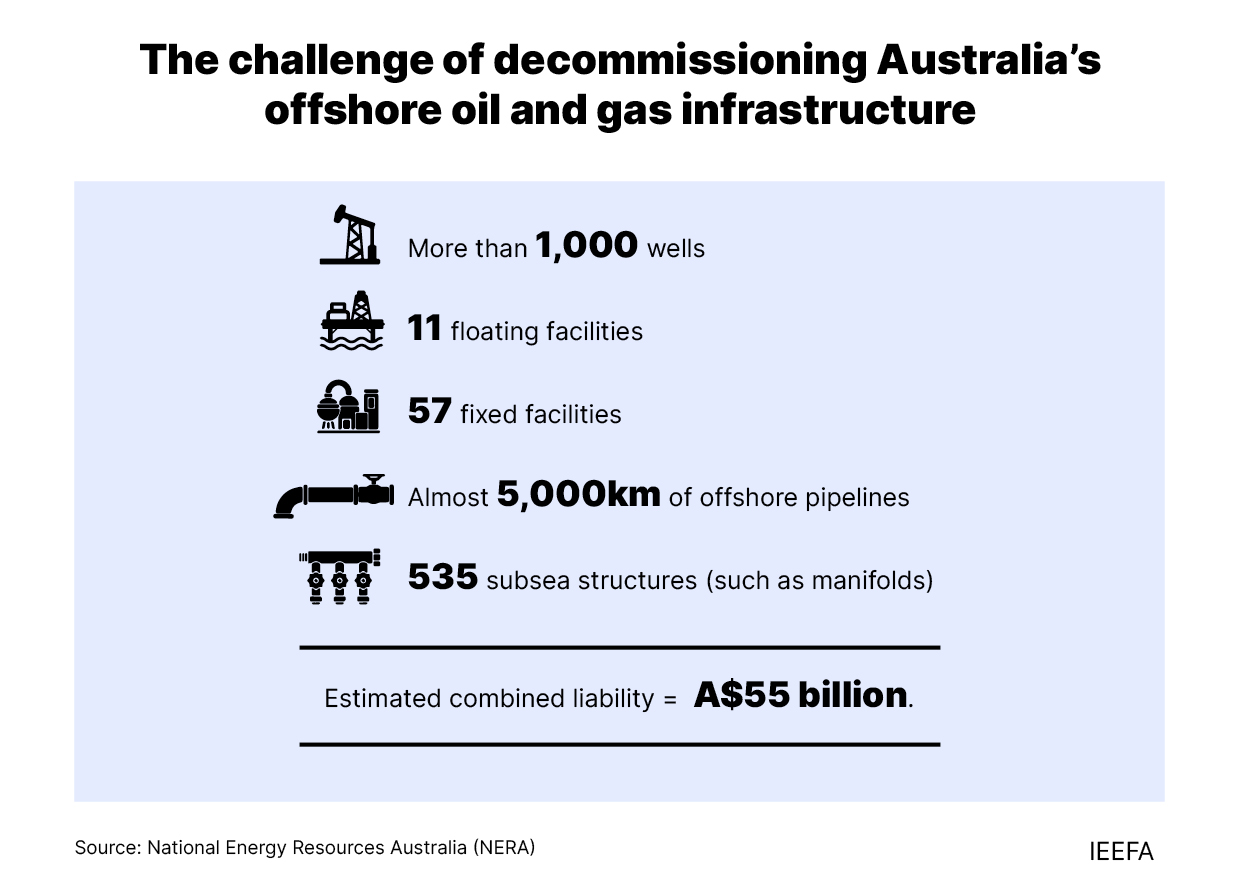

The challenge of decommissioning Australia's offshore oil and gas infrastructure presents a significant risk for the oil and gas industry, with a range of assets nearing the end of their useful life amounting to an estimated combined liability of A$55 billion.

It is important that investors are provided with a full picture of the likely scope, timing and costs of decommissioning, but company disclosures in this area are currently inadequate.

A rapid phase-out of oil and gas amid accelerated climate action could reduce the industry’s ability to meet its decommissioning liabilities, leaving governments at risk of carrying the costs.

Australia’s oil and gas industry faces a big challenge to decommission offshore oil and gas infrastructure over the coming decades, creating risks for investors and governments.

In recent decades, Australia has seen significant investment in offshore oil and gas infrastructure, particularly in Victoria and Western Australia. The oil and gas industry now faces a material risk as this infrastructure reaches the end of its useful life.

National Energy Resources Australia (NERA) reports that there is significant offshore asset stock in Australia that will require decommissioning, including:

- More than 1,000 wells

- 11 floating facilities

- 57 fixed facilities

- Almost 5,000km of offshore pipelines

- 535 subsea structures (such as manifolds)

NERA estimates the combined liability associated with the decommissioning of existing offshore infrastructure at US$40.5 billion (about A$55 billion).

According to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA), the task of decommissioning Australia’s offshore oil and gas infrastructure will be “complex, expensive, span many years and introduce many new and significant safety, environmental and well integrity risks”. The scale of Australia’s decommissioning task poses a range of risks for investors and governments, including material financial risks.

Companies may also seek to avoid or defer decommissioning costs by proposing that infrastructure be repurposed for carbon capture and storage (CCS). For example, Santos withdrew decommissioning plans for the Bayu-Undan field following a proposal to use it for CCS (despite not releasing any cost estimates or technical studies that demonstrate its feasibility).

The much-publicised liquidation of Northern Oil and Gas Australia (NOGA) in 2019, after its acquisition of the Laminaria and Corallina oil fields from Woodside in 2016, illustrates this risk. Following liquidation, liability for decommissioning the Northern Endeavour oil facility initially fell to the Australian government. In response, the government ultimately imposed an industry-wide levy to cover decommissioning costs, a move that was criticised by the then Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association (recently renamed Australian Energy Producers).

The government also implemented a number of changes to the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 in 2021, including: strengthening trailing liability provisions (for titleholders who sell their interests); requiring NOPSEMA approval of any changes of interest or control of more than 20%; and increasing financial assurance requirements. While these reforms have improved Australia’s regulatory framework, in IEEFA’s opinion there remains scope for government to do more.

Key risks could affect oil and gas decommissioning

Several issues and risks could affect future decommissioning in Australia:

- Limited decommissioning activity to date means Australia is relatively inexperienced in decommissioning offshore infrastructure, raising concerns about a possible lack of technical expertise. This could be compounded by shortages of equipment and workers, which may make it difficult for companies to meet their decommissioning obligations.

- International experience demonstrates that decommissioning activity can be subject to significant cost overruns (as discussed below). Supply chain uncertainty can make it difficult for companies to accurately budget for their decommissioning costs, which may be compounded by a lack of reliable benchmarking. A study undertaken by Australian and Chinese researchers found that current decommissioning databases are incomplete, leading to inaccurate and subjective cost estimation and incomplete environmental impact estimation.

- Decommissioning offshore oil and gas infrastructure poses obvious environmental risks, with decommissioning in the North Sea indicating that large infrastructure and sealed wells present the greatest risks. However, these risks are poorly understood, including risks related to the release of metals and naturally occurring radioactive materials, and the leaking of hydrocarbons from capped wells. Moreover, the risks associated with alternative approaches to full removal of infrastructure (i.e. “in situ” decommissioning) are not yet fully understood in an Australian context. Recent regulatory notices issued by NOPSEMA to a number of Australian gas producers provide an indication of the environmental risks that could arise.

- There may be limitations or risks around the ability of titleholders to repurpose offshore infrastructure to avoid or defer decommissioning expenditure, including for CCS projects.

- The energy transition creates risks around the need for increased provisioning to meet decommissioning liabilities if a shift away from oil and gas results in shortened project lives. In addition, jurisdiction-level approaches to decommissioning can create risks for governments in the event that a rapid decline of the oil and gas sector results in ‘economic stranding’ of oil and gas assets.

- Australia’s new trailing liability provisions mean that a wide range of companies now face ongoing liability for the costs of decommissioning offshore oil and gas infrastructure, even where they were not its direct owner.

Investors need better information

It is important that investors are provided with a full picture of the likely scope, timing and costs of decommissioning. However, a review by the Australian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) found that company disclosures related to decommissioning are inconsistent and often limited, with reporting of decommissioning obligations generally being “minimalist”. While NERA has published aggregated estimates of Australian offshore oil and gas assets, limited company disclosures prevent “shareholders from obtaining an accurate picture of assets due for decommissioning in the short, medium and long term”. In other words, company disclosures do not provide a clear picture of the scope or timing of required decommissioning.

Where companies have published information on their intended decommissioning activities, it can be based on plans that may not reflect the nature of decommissioning actually required. Under Australian regulations, full decommissioning of oil and gas infrastructure is considered to the “base case”, with companies able to apply for approval from the regulator for alternative approaches (such as in situ decommissioning).

The ACCR found that several ASX-listed companies have published decommissioning provision estimates based on plans that involve leaving some infrastructure in place, despite not having yet received the necessary regulatory approvals (though a few of these companies have included some guidance in their reporting on the additional costs that might be incurred if approval is not granted).

As an example, in June 2022 Esso published decommissioning plans for its Gippsland Basin operations, which proposes leaving in place any structures located at a depth of 18 to 36 metres, without having received approval yet from the regulator. The scope of decommissioning could be larger if the regulator requires greater removal of infrastructure than anticipated by Esso.

The costs of decommissioning offshore infrastructure will in practice be influenced by a range of factors, including the type and complexity of infrastructure to be decommissioned, the decommissioning approach (full removal or alternative approaches), and the legislative and regulatory environment.

Different assumptions around the approach to decommissioning are likely have a material impact on the estimated costs. For example, NERA estimates that leaving transport pipelines in place (in situ decommissioning) could reduce Australia’s estimated US$40.5 billion decommissioning costs by about 15%, or US$5.9 billion.

However, the ACCR found that ASX-listed companies with decommissioning obligations currently report “restoration provision balances as a single figure, along with some explanatory notes”. The ACCR accordingly recommends that companies clearly explain major assumptions underpinning provisioning.

Shareholders also face the risk that actual decommissioning costs are higher than those estimated by oil and gas companies. International decommissioning experiences demonstrate this risk – the actual costs of several decommissioning projects in the North Sea were on average 76% higher than estimated costs (due to limitations in the approaches used to estimate costs). Specifically, a lack of benchmarks and limited scope for standardisation have contributed to the cost overruns observed in the North Sea.

Decommissioning costs are also likely to increase with any additional investment in new offshore oil and gas infrastructure (as proposed by several Australian gas producers). NERA notes that its estimate of future decommissioning costs is based on the existing installed infrastructure (as of April 2020) and does not include any allowance for new infrastructure.

Rapid oil and gas phase-out would increase the risk of governments paying the bill

The scope and costs of Australia’s decommissioning challenge is large, and the ability of companies to meet their obligations will likely depend on their financial viability. However, a rapid phase-out of oil and gas due to accelerated climate action could change the financial situation of companies and reduce the industry’s ability to meet its decommissioning liabilities.

The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law noted these risks and stated that: “… the potential rapid decline in offshore oil and gas is a matter of public concern because governments often sit as the ‘decommissioner of last resort’. It added that: “A formal assignment of legal liability, however, does not guarantee that decommissioning will occur or that funds will be available when decommissioning obligations arise. Even jurisdictions with extensive decommissioning experience and well-tested decommissioning regulations may be unprepared for the industry-wide decline associated with a rapid phase-out of offshore oil and gas production.”

There are steps that government can take to address the risks arising from a rapid phase-out of oil and gas. For example, the Sabin Center recommends four steps to protect the public in a rapid phase-out scenario:

- Require companies to create and regularly update comprehensive decommissioning plans.

- Re-examine decommissioning security mechanisms such as collateral packages, guarantees and funding structures to ensure they are compatible with a rapid phase-out scenario.

- Evaluate and plan for the tax consequences of industry-wide decommissioning in the event that rapid phase-out affects the entire oil and gas industry.

- Evaluate and modify stabilisation clauses to accommodate a rapid phase-out.

Australia’s decommissioning challenge poses a range of risks. A rapid phase-out of oil and gas could increase these risks and lead to governments needing to take on responsibility for decommissioning activities. The Australian government should carefully consider the need for further reform to ensure that oil and gas companies can meet their decommissioning obligations.