Australian met coal export forecast downgraded yet again as BHP reportedly considers an exit

Key Findings

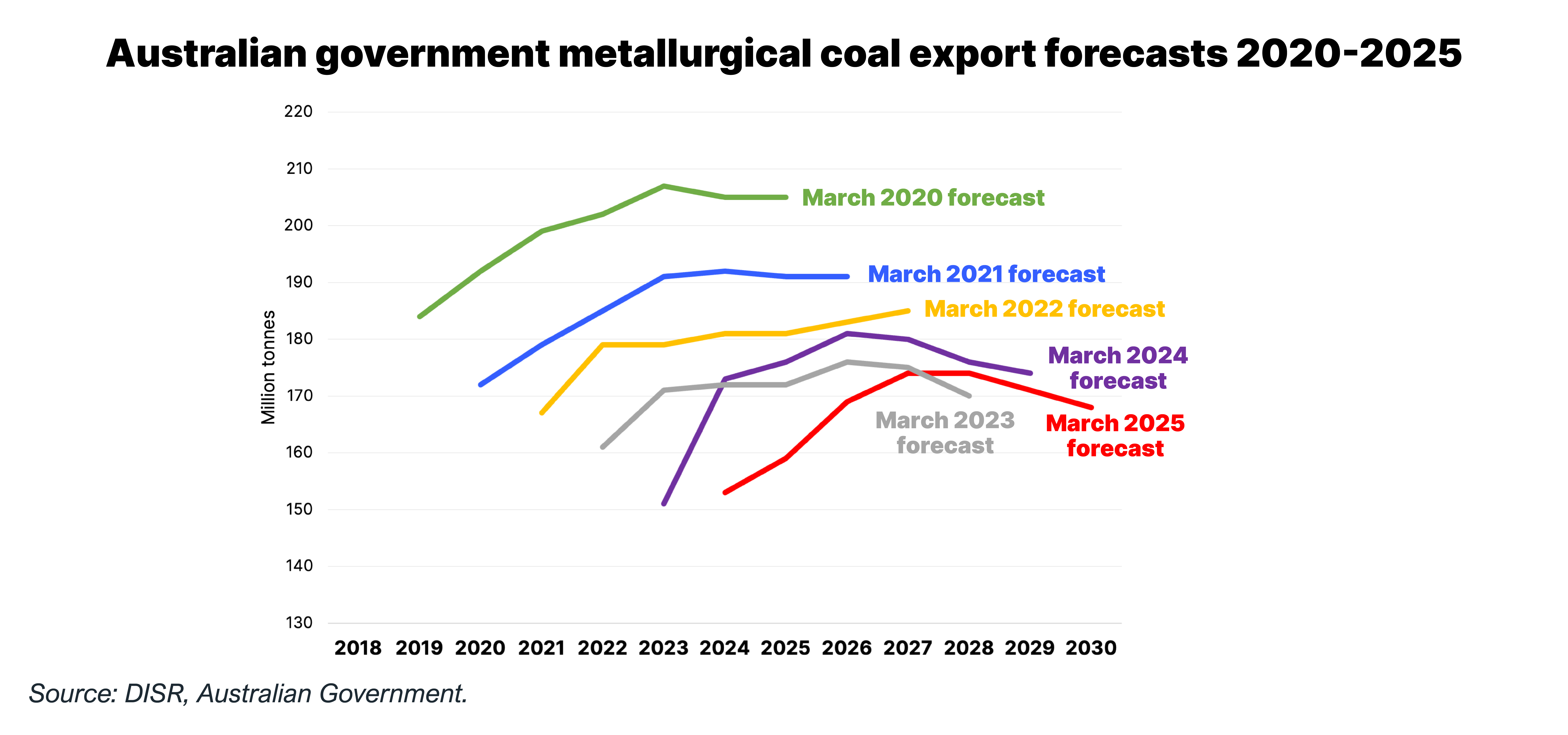

The Australian government has consistently overestimated Australia’s met coal exports over the past six years, needing almost constant downward revisions year-to-year, while actual exports have been in decline over this period.

Despite carbon capture's long track record of failure, BHP maintains that carbon capture and storage will allow continued use of its met coal and lower-quality, blast furnace-grade iron ore while addressing its huge Scope 3 carbon emissions problem.

Reuters recently reported that BHP has considered spinning off iron ore and coal businesses, suggesting some acceptance that these divisions have declining futures that cannot be saved by CCS.

The Australian government has continued the reduction of its metallurgical (met) coal export forecast in the face of the steel technology shift away from coal.

In the Department of Industry, Science and Resources’ (DISR) March 2025 Resources and Energy Quarterly – which contains its annual medium-term forecasts – 2025 met coal exports are forecast at 159 Million tonnes (Mt). This is down 10% from levels forecast last year, and down 22% from the 2020 forecast. Expected exports out to 2030 have also been reduced.

DISR has consistently overestimated Australia’s met coal exports over the past six years, needing almost constant downward revisions year-to-year, while actual exports have been in decline over this period.

This year, DISR forecasts exports will rise for a few years before peaking in FY2027-28 and then declining again out to 2030 as imports by China, by far the largest steelmaker in the world, continue to decline amid waning steel demand.

This doesn’t quite square with the rosy met coal outlook the Australian coal industry likes to give us. DISR highlights that the steel technology shift away from coal-consuming blast furnaces to direct reduced iron (DRI) and electric arc furnaces (EAF) will reduce overall met coal demand through to 2030 despite a forecast modest increase in global steel production.

Neither DRI nor EAF iron and steelmaking technologies – both mature and used at scale today – use coal.

As DISR states, “Low-emissions steelmaking has been rising, with gradual increases in the proportion of electric arc furnace (EAF) produced steel in most major steel producers. This share is forecast to gradually rise over the outlook to 2030. To date EAF operations have largely relied on recycled scrap steel as feedstock but are now looking to DRI as an alternative.”

DISR also points out that in the EU, which is leading the global steel technology transition, met coal imports “seem to be in a long-term structural downturn”.

There are also significant downside risks to the latest forecast. India is expected to overtake China to become the world’s largest met coal importer by 2028 (94Mt). However, this could be affected by any success India has in dealing with its growing energy/resources security risks as it targets increased domestic met coal production from 67Mt to 140Mt a year by 2030.

Moreover, DISR’s forecast could not have taken into account the potential economic impact of trade tariffs suddenly imposed on Australia’s met coal customers. Japan, India, China, South Korea and Taiwan are Australia’s key met coal export destinations, and are threatened with respective tariff rates of 24%, 26%, 145%, 25% and 32% by the US.

The CCS mirage is fading fast

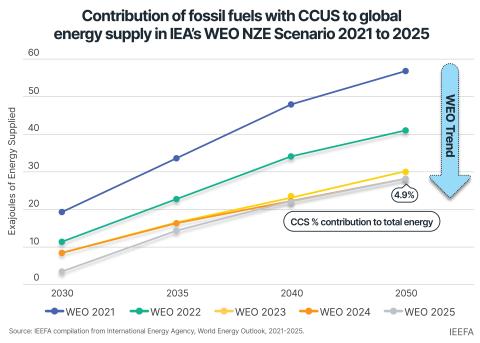

DISR’s gloominess on the met coal outlook continued, “Unlike iron ore, metallurgical coal cannot be used in any green steel pathway without CCS [carbon capture and storage]”. Unfortunately, for the Australian met coal sector, CCS for steel is going nowhere fast, in common with other sectors.

Despite the gas sector insisting for years that CCS will sustain long-term consumption of the fossil fuel, Woodside recently admitted that the technology was simply too expensive to implement. Last month, ExxonMobil and Woodside withdrew their South East Australia Carbon Capture Hub plan in the Gippsland Basin.

Despite CCS’s long track record of failure, BHP maintains that carbon capture will allow continued use of its met coal and lower-quality, blast furnace-grade iron ore while addressing its huge Scope 3 carbon emissions problem as the steel sector decarbonises. BHP does not have a measurable Scope 3 emissions reduction target.

In contrast, BHP’s iron ore peers are targeting increased production of higher-grade iron ores that can be used in DRI processes without coal. DISR noted in its March 2025 outlook, “As the production of green iron and steel rises, the iron ore product mix will gradually shift towards higher grade ores and concentrates suitable for producing DRI.”

But BHP is sticking firmly with lower-grade ore for processing in blast furnaces that consume its coal. Most other diversified miners are also divesting their met coal operations.

Will BHP eventually just divest its emissions problem away?

However, Reuters recently reported that BHP has considered spinning off its iron ore and coal divisions.

The plan – not put into action – seems to acknowledge that BHP’s iron ore and met coal divisions are considered declining businesses in contrast to its focus on future-facing commodities such as copper. Because CCS is in no position to effectively decarbonise blast furnaces, BHP’s met coal and blast furnace-grade iron ore face a challenged future in a decarbonising steel sector. Lower-grade iron ore is also exposed to declining steel demand in China.

A divestment of its iron ore and met coal would also rid BHP of its biggest carbon emissions problem.

However, having failed to acquire Anglo American, targeted mainly for its copper assets, BHP relies on its highly cash-generative iron ore business to support further investments in future-facing commodities.

That could change if BHP were to target Anglo American again with success. Anglo is in the process of selling its own met coal operations to Peabody, which is now reviewing the deal following an explosion at one the mines involved. If Peabody were to walk away from the deal, this may prompt BHP to approach Anglo again.

Regardless of what plays out, if BHP was even considering spinning off its iron ore and met coal businesses, it suggests some acceptance that these divisions have declining futures that cannot be saved by CCS. BHP should stop pretending otherwise.