IEEFA U.S.: Investors would best avoid two proposed Virginia combined-cycle gas plants

Investors should think twice before putting any money into two proposed natural gas-fired combined-cycle power plants in central Virginia. The rapidly moving transition to non-fossil generation resources is almost certain to turn the two plants, which would be only a mile apart, into stranded assets well before the end of their normal life expectancies.

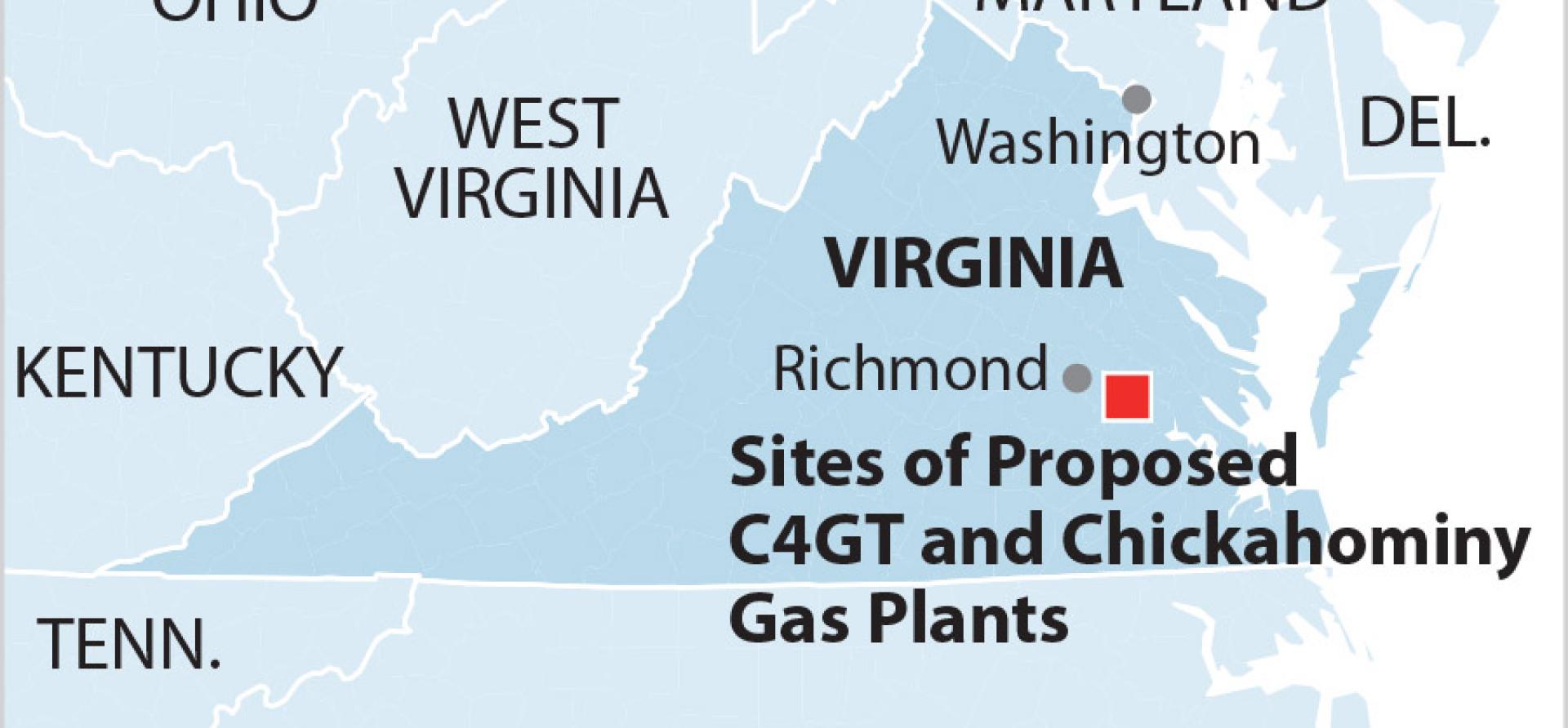

The two plants, the 1,060-megawatt (MW) C4GT unit and the 1,650MW Chickahominy facility, would feed into PJM, the 13-state (plus the District of Columbia) transmission operator that already has far more generating capacity than it needs. The system’s peak demand this past summer was 144,266MW on July 20; total available capacity topped 187,000MW, giving PJM a reserve margin of just under 30%—almost double its target margin of 15.5%.

The two plants, the 1,060-megawatt (MW) C4GT unit and the 1,650MW Chickahominy facility, would feed into PJM, the 13-state (plus the District of Columbia) transmission operator that already has far more generating capacity than it needs. The system’s peak demand this past summer was 144,266MW on July 20; total available capacity topped 187,000MW, giving PJM a reserve margin of just under 30%—almost double its target margin of 15.5%.

This was not a pandemic-induced phenomenon. The system’s reserve margin in 2019 was 32.8%, when PJM had both a higher demand peak and more available generation. PJM’s peak load has been essentially flat since 2002, when it hit 150.8 gigawatts. Taken together, these metrics show no need for C4GT and Chickahominy.

Beyond that are questions about their longevity. The plants would have to comply with mandates in two new Virginia energy and environmental laws. The Virginia Clean Economy Act requires that all electricity in the state come from non-fossil resources by 2050. Although much of the commentary regarding this new law has focused on its impact on the state’s two investor-owned utilities, Virginia Power (a subsidiary of Dominion Energy) and Appalachian Power (a unit of American Electric Power), it applies just as forcefully to C4GT and Chickahominy. Both would have to close by 2050.

The two units are also covered by Virginia’s 2020 Clean Energy and Community Flood Preparedness Act. The act makes the state part of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a program by 10 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states to cap carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector. Broadly speaking, RGGI limits the amount of CO2 that may be emitted by power plants larger than 25MW; C4GT and Chickahominy would be required either to reduce their emissions to meet the cap or buy allowances to cover their releases. Funds raised from the sale of the allowances are reinvested in regional energy efficiency and renewable energy initiatives. Virginia is set to join RGGI in January.

Virginia’s RGGI membership would clearly have an impact on the economic competitiveness of C4GT and Chickahominy. The new RGGI requirements would likely raise the costs of the plants’ electricity generation and make it harder to sell into the already-oversubscribed PJM market. The cost of complying with RGGI is uncertain, but a senior official with the Virginia Department of Environment Quality estimated this year that exempting the two plants from RGGI for three years would have saved them a total of $131 million.

Both proposed projects also would risk court fights on environmental justice issues,* posing both reputational and financial dangers for investors. Such issues have not played a major role in most past permitting decisions, but a precedent-setting court ruling in January regarding another proposed Virginia natural gas project could change that.

Environmental justice is not merely a box to be checked

The January ruling concerned the planned location of a compressor station in the predominantly Black community of Union Hill in Buckingham County. The station was designed to be part of the now-cancelled Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the state’s approval of the station, writing: “Environmental justice is not merely a box to be checked, and the board’s failure to consider the disproportionate impact on those closest to the compressor station resulted in a flawed analysis.”

“What matters,” the court continued, “is whether the [State Air Pollution Control] board has performed its statutory duty to determine whether this facility is suitable for this site, in light of EJ [environmental justice] and potential health risks for the people of Union Hill. It has not.”

In the ruling’s aftermath, Gov. Ralph Northam signed legislation establishing the Virginia Council on Environmental Justice as a permanent advisory body to state government. It remains to be seen if this will affect daily decision-making by government agencies, but it points to potential problems for the two planned gas projects located in Charles County, a majority-minority area east of Richmond. Opponents of C4GT and Chickahominy say the plants’ developers are using larger regional geographic areas to understate localized minority impacts—setting the stage for potential legal fights in the future.

THE SHEER SIZE OF THE PROPOSED CHICKAHOMINY FACILITY IS ALSO AN ISSUE, particularly given a lack of transparency regarding the plant’s backers. The facility would be the fifth-largest merchant gas-fired power plant in the U.S. and would carry an estimated price tag of $1.63 billion. The four larger merchant gas plants were developed and are owned by corporations with sizable balance sheets and longstanding track records in the energy arena. They include Florida Power and Light, Southern Power and Exelon Power. In contrast, the public face of the Chickahominy project is Balico LLC, a company that appears to be operating out of a townhouse in Herndon, Va., near Dulles International Airport. There is clearly backing of some kind behind the company, given the redactions in Balico’s state commission filings, but those companies or individuals have not been willing to be publicly associated with the project.

Legislative changes and market fundamentals have changed significantly in the past year

The public face of the C4GT project is a small family-owned company in Michigan, Novi Energy. The company’s website touts its commitment to “clean and sustainable energy solutions” but indicates no experience in developing large-scale power projects—certainly none on the scale of the 1,060MW C4GT proposal. Meanwhile, the source of the money behind C4GT is clearly from a unit of Ares Management, a Los Angeles-based investment firm that oversees $179 billion in assets.

Ares has developed other combined-cycle plants in PJM, most recently the 488MW Birdsboro project in Pennsylvania that came online last year. Ares subsequently sold portions of Birdsboro, and Tokyo Gas now owns 33% of the facility and a group of other Japanese firms owns another 33% of the facility. Whether Ares will sell stakes in the C4GT plant if it is built is uncertain, but potential investors deserve to know that the risks—legislative changes and market fundamentals—have changed significantly in the past year.

During a May 2020 hearing on the gas pipeline infrastructure that Virginia Natural Gas (VNG) proposed building to supply the C4GT project, a Virginia Corporation Commission administrative law judge asked the VNG representative: “How are we going to allocate the risk, and who’s going to be holding the bag if this plant doesn’t get built?”

Investors considering backing either the C4GT or Chickahominy gas projects would do well to consider a similar version of the same question: If the plants are built and then undercut by the rapid transition to a cleaner grid, who will be left in the lurch?

Dennis Wamsted ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy analyst.

*The Environmental Protection Agency defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

Related Items:

IEEFA U.S.: Appalachian frackers report $504M in negative free cash flow despite capex slashing

IEEFA U.S.: Investors in gas-fired projects in largest regional power system face substantial risks