IEEFA: Despite higher coal prices, U.S. coal recovery looks weak by most measures

Coal prices have surged to the highest level in years in the U.S., and have soared in international markets. These high prices should significantly boost revenues and profits at coal mining companies—a remarkable turnaround from just a year ago, when the world’s pandemic-induced economic swoon sent export prices and demand tumbling.

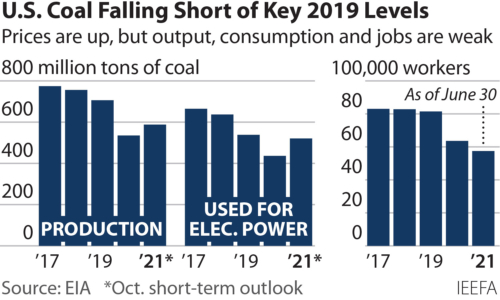

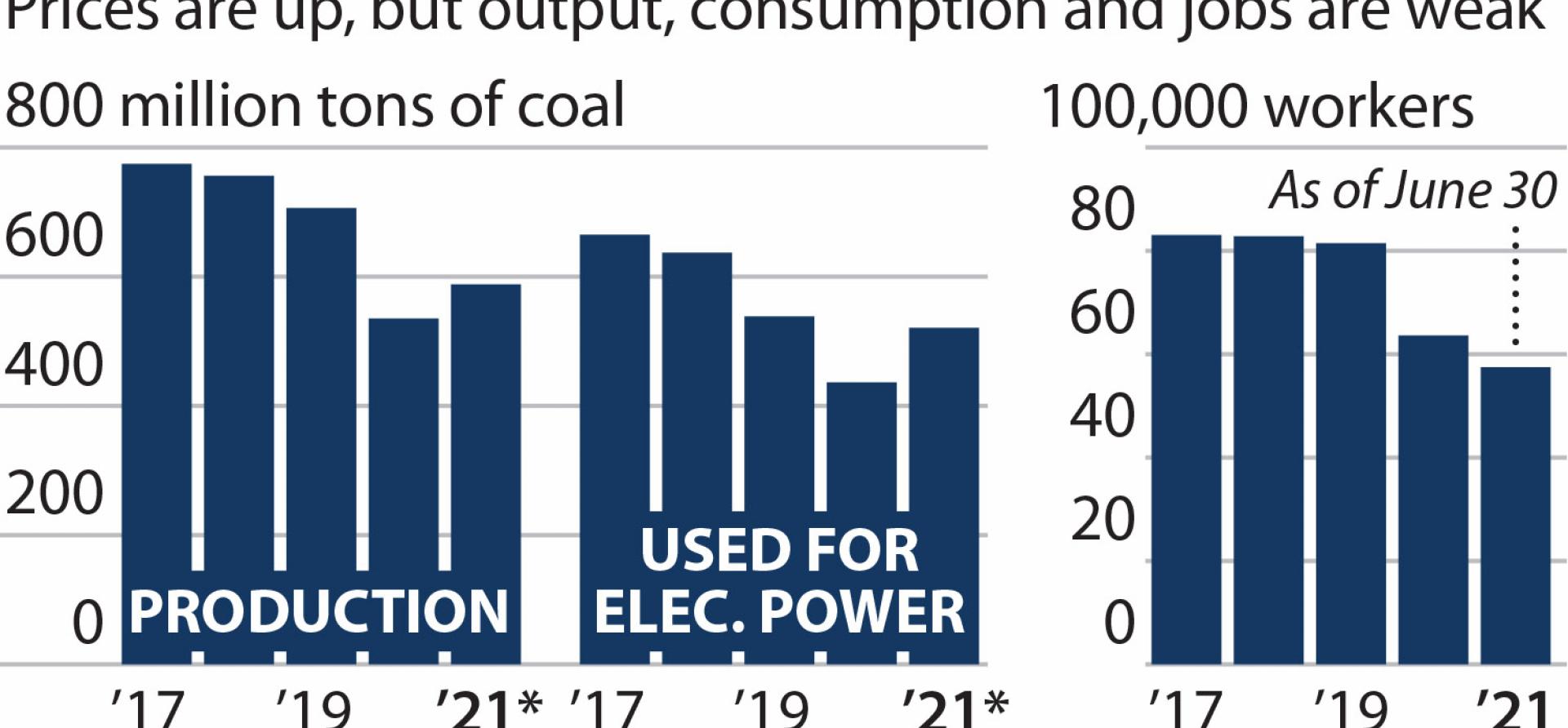

Yet by most measures—including coal production, consumption for electric power, mining jobs and coming coal-plant retirements—the sector will barely rebound to 2019 levels, a far more telling comparison than to 2020, the worst year for U.S. coal in decades.

U.S. coal production

Take U.S. coal production, the broadest measure of the industry’s condition. This year’s output is expected to be 588 million tons, up 10% from 2020’s 535 million tons, according to October’s Short-Term Energy Outlook from the Energy Information Administration. That seems like a decent rebound, but it’s actually 118 million tons lower than in 2019, and, other than 2020, would be the lowest since 1971.

Coal use for electric power

Coal use for electric power is up over last year, too. The EIA’s latest outlook expects an 84-million-ton, or 19%, increase, to 521 million tons, compared with the 437 million tons used in 2020. Once again, this appears to be a substantial recovery—except that it’s lower than 2019’s 539 million tons. This is significant because more than 90% of the coal consumed in the U.S. is used to generate electricity.

Coal and gas together continue to lose ground to renewables

This poor recovery in coal use looks even worse considering the price of natural gas rose 83% from $2.47 per thousand cubic feet in the third quarter of 2019 to $4.53 in the third quarter of this year. And, as IEEFA has noted about the energy transition in U.S. electricity markets, coal and gas together have not gained market share, and are instead continuing to lose ground to renewables. This is a trend that will continue for the foreseeable future, given the ongoing construction boom in utility-scale solar and wind. If anything, high prices for coal and gas, if sustained, are likely to cause the switch to renewables to accelerate.

Coal’s domestic market continues to shrink, too. More than 80GW of coal-plant retirements—more than one-third of the current operating capacity—are already scheduled to be retired by the end of 2030. IEEFA estimates these units used 166 million tons of coal in 2019, which would cut demand to about 375 million tons by the end of the decade, and this does not account for any new retirement announcements that could be made. On top of this, the remaining coal plants are likely to run less and less. EIA data shows the capacity factor for coal plants (a measure of how much of their generating potential is actually used) fell from 62.8% in 2011 to just 40.2% in 2020. IEEFA estimates that even a modest decline in capacity factors at the plants expected to operate after 2030 could result in a further loss of more than 80 million tons, bringing the total drop in coal demand from the U.S. power sector to about 250 million tons. In other words, coal’s largest U.S. market could shrink as much as 50% in just nine years.

U.S. coal mining jobs continue to decline

Another sign that coal mining isn’t recovering is the scale and timing of job losses. Nearly 24,000 jobs have been cut—a 29% decline—since 2019, when an average of 81,478 people were working for either coal-mine operators or contractors. This includes a loss of more than 6,100 jobs between 2020 and the first half of 2021, according to the latest figures from the Mine Safety and Health Administration, leaving just 57,497 workers in coal mining. That’s just half the number employed as recently as 2014.

The high cost of coal is making switch to lower-cost renewables even more compelling

Exports

With surging prices for coal in international markets—a complete turnaround from a year ago—coal exports should be a bright spot for American producers. No doubt for the companies that are exporting, there will be a significant boost to their bottom lines, because volumes are set to grow by 34% this year compared with 2020, to 92.6 million tons. Yet even here, this only returns exports to the 2019 level of 93.8 million tons, and the EIA outlook sees almost no further growth in 2022, when it expects 94.8 million tons to be sold abroad.

It is not surprising that coal has staged at least some comeback over 2020—by many measures the worst year for the industry in decades. What is surprising is that the rebound has fallen short of even 2019 in the critical measures of production, consumption by the power sector and jobs. This year’s high coal prices are likely to improve the weak finances at many mining companies, at least temporarily, but they won’t change the sector’s long-term decline. If anything, the high cost of coal is making the economics of switching to lower-cost renewables and storage even more compelling, and could result in utilities and other power producers accelerating their shift away from using coal.

Seth Feaster is an IEEFA Energy Data Analyst, [email protected]

Related items:

IEEFA U.S.: Surging generation from solar, wind on track to push renewable market share to 30 percent by 2026, October 2021

IEEFA Canada: Teck’s possible met coal exit an ominous sign for U.S. coal companies, September 2021

IEEFA U.S.: The coal-to-renewables transition takes off, May 2021