India may not be the promised land for Australia’s met coal exports after all

Key Takeaways:

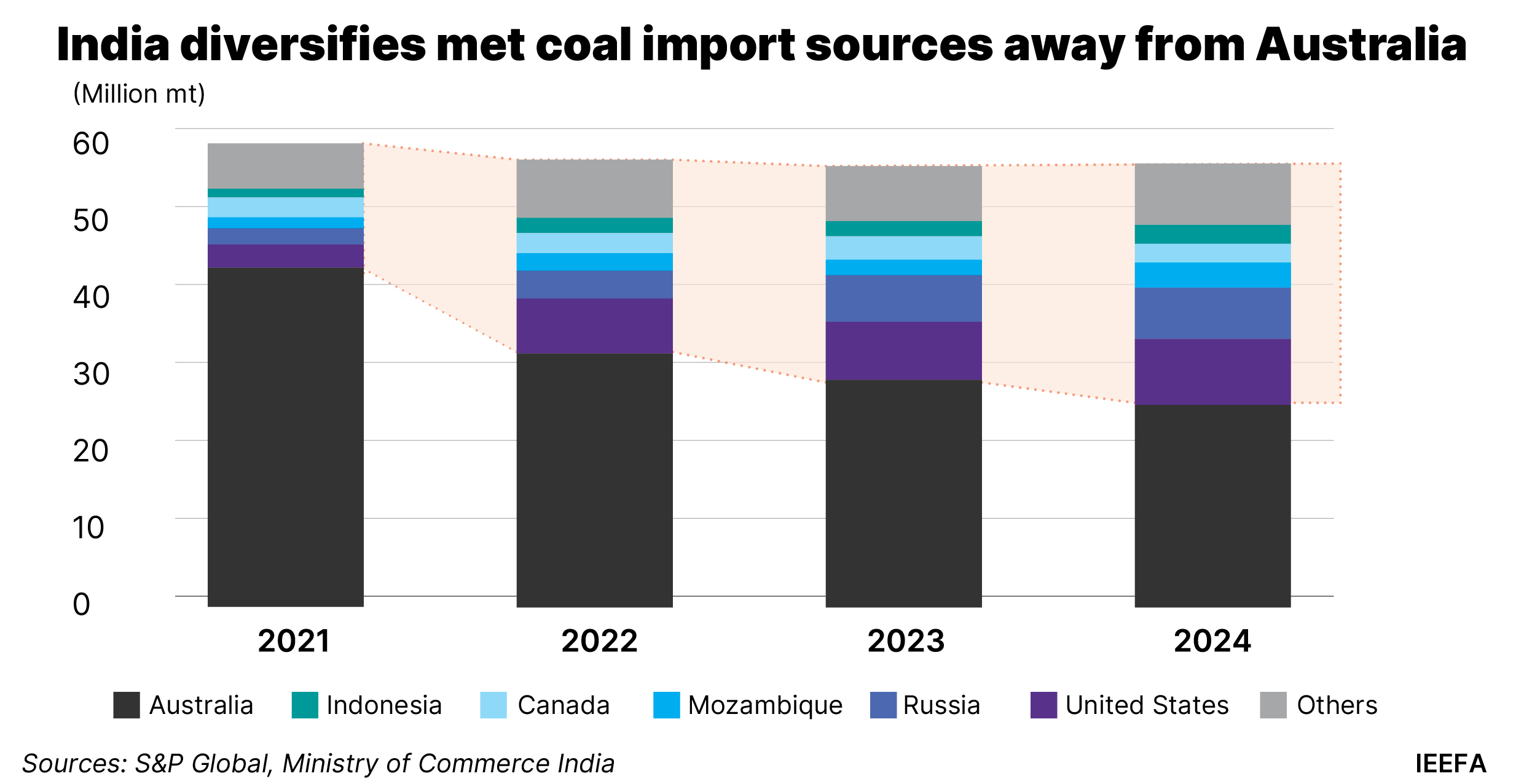

Australian metallurgical (met) coalminers such as BHP and Whitehaven suggest India will prop up long-term demand. However, growing Indian demand will not be enough to stop the overall decline in the seaborne met coal market.

Australia’s exports to India have been falling since 2021. China’s total met coal imports are forecast to decline by 100 million tonnes by 2035, giving Indian steelmakers an opportunity to continue to reduce reliance on Australian met coal.

India’s growing energy security concerns prompted it to target increased domestic met coal production to reduce reliance on imports.

In the longer term, India will be incentivised to shift away from coal-based steelmaking.

1 October 2025 (IEEFA Australia): Optimism that India’s demand for metallurgical coal will sustain Australia’s export industry ignores growing trends in that key market, according to a briefing note released today.

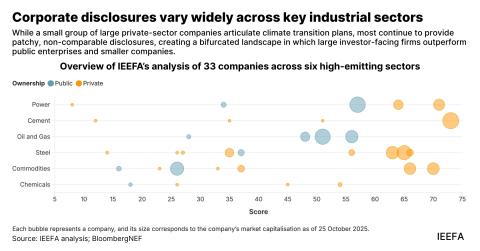

Both BHP and Whitehaven Coal continued to be bullish on the prospects for long-term met coal demand from India in their recent results. However, the landscape is changing in India, where growing energy security concerns are leading to India diversifying away from Australian met coal, boosting domestic coal production and developing met coal-free steelmaking, as highlighted in India’s met coal imports will disappoint Australian coalminers.

India’s aim is clear: greater energy security through reduced reliance on coal imports from Australia.

This is bad news for Australia’s met coalminers but they – and the federal government – don’t seem to have got the memo, say the authors Simon Nicholas, IEEFA’s global steel lead, and Saumya Nautiyal, energy finance analyst, South Asian steel.

BHP and Whitehaven ship significant volumes of their met coal to India, but there were no signs of any headwinds in their FY2025 reports, as “confidence in India’s longer-term growth remains strong” with “growing and resilient demand for decades to come”.

While India’s increased steel production will boost met coal imports, it will not offset declining global demand, particularly from China. Amid escalating tariffs and trade embargoes, Australia’s competitors are queueing up to supply India’s met coal, led by Russia.

“Indian steel mills have been preferencing cheaper Russian met coal over Australian coal, and have been adjusting their coking coal blends to suit Russian volumes,” Mr Nicholas says

Joining the list of countries displacing Australian coal in India is the US, whose exports to China have collapsed, plus Mozambique, Mongolia (via Russia) and potentially Canada. As a result, Australia’s exports to India have been falling since 2021, down 11% in 2024 alone.

“India’s declining imports of Australian met coal reflects an overall decline in Australia’s met coal exports since 2019,” Mr Nicholas says. “The decline was initiated by China’s unofficial ban on Australian coal imports that year, from which volumes have never fully recovered. India’s diversification of import sources has added to Australia’s continued decline in export volumes.

“S&P Global forecasts that China’s met coal imports will fall by around 100 million tonnes per annum over the next decade, giving India the opportunity to continue to diversify imports away from Australia.”

India’s lack of domestic met coal production is another misconception held by Australian exporters. Whitehaven recently dismissed India’s met coal reserves as “next to nothing”, while Yancoal went further: “The advantage of the Indian market is that India does not produce its own metallurgical coal.”

India’s national Atmanirbhar (self-reliant) policy push targets coal, with the government ramping up domestic thermal coal production beyond 1 billion tonnes in 2024 while reducing imports for the past two years. Met coal is next in its sights.

“India does produce met coal, and its evolving policies and production targets are creating a path towards reduced import dependence,” Mr Nicholas says. “The government is focused on tackling the issue by building domestic capacity, taking inspiration from its success in scaling up thermal coal production.”

Longer term, India will be incentivised to shift to steelmaking technology that doesn’t use met coal, driven by concerns over both supply and price.

The Australian government consistently overestimates its met coal export forecasts. Meanwhile, both Whitehaven Coal and BHP continue to highlight to their investors that limited future supply will drive up prices for met coal, an issue for price-sensitive India steelmakers.

Alternative steelmaking pathways that improve India’s energy security – such as scrap-steel recycling and hydrogen-based steelmaking – will only become more attractive to India if met coal prices become structurally higher amid limited new supply.

“Although global green hydrogen prices have not declined as fast as previously expected, Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts that they will be competitive in India and China in the 2030s,” Mr Nicholas says.

Aligned with action on its energy security concerns, India’s major steelmakers plan to reach net zero emissions 20 to 25 years ahead of India’s national target, with Tata aiming for 2045, Jindal for 2047 and JSW for 2050.

“These ambitions depend on reducing coal use, and align with the need for action on India’s recognised and growing energy security risk from its reliance on met coal imports,” Mr Nicholas says.

“In both the short and long term, Australia’s met coalminers face significant downside risks when it comes to India’s met coal demand.”

Read the note: India’s met coal demand will disappoint Australian miners

Media contact: Amy Leiper, ph +61 414 643 446, [email protected]

Author contacts: Simon Nicholas, [email protected], Saumya Nautiyal [email protected]

About IEEFA: The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) examines issues related to energy markets, trends, and policies. The Institute’s mission is to accelerate the transition to a diverse, sustainable and profitable energy economy. (ieefa.org)