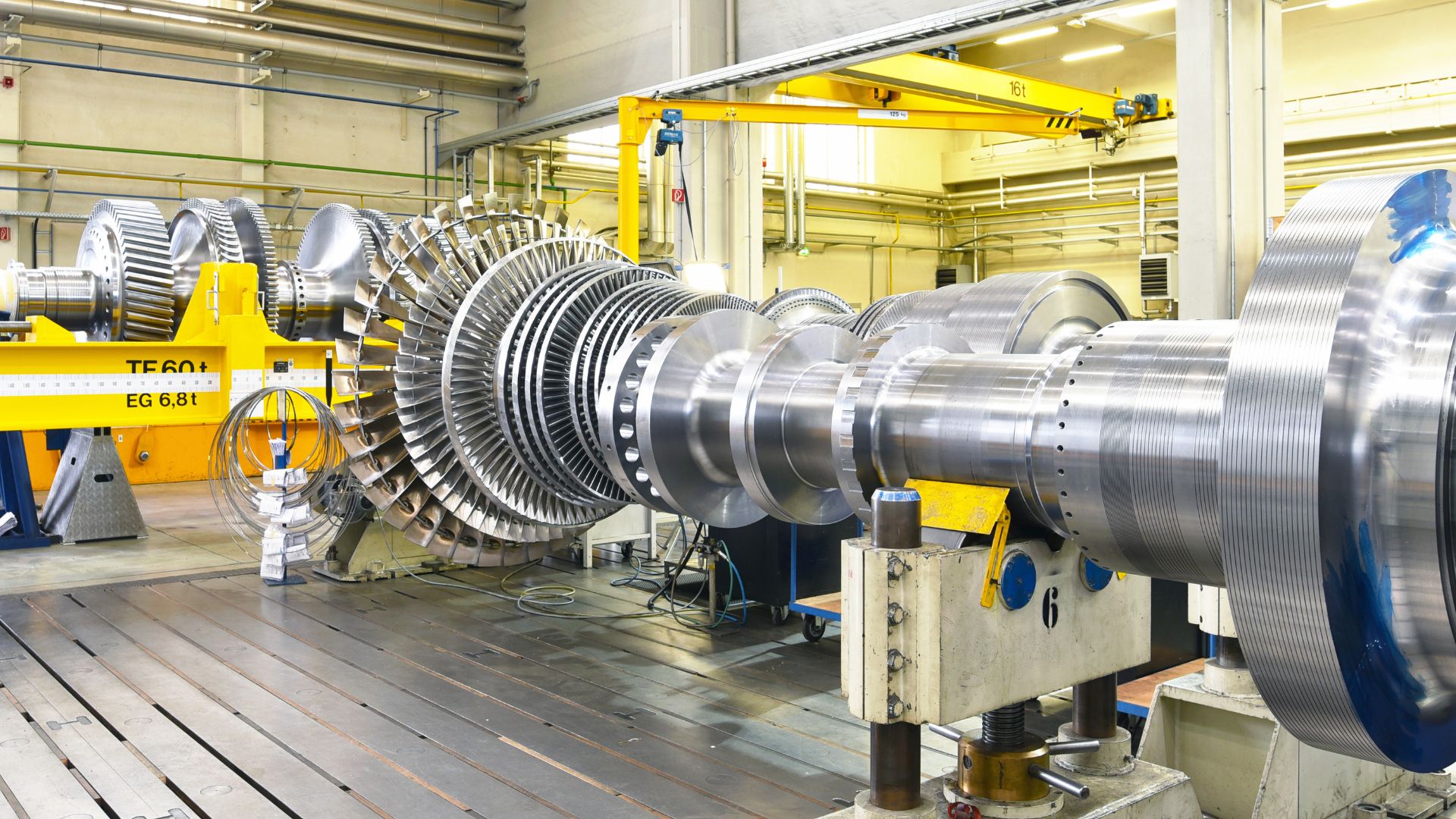

Global gas turbine shortages set to increase delays and costs for gas-to-power projects in Vietnam and the Philippines

Turbine production bottlenecks add to a lengthy list of regulatory and financial challenges delaying gas power expansion in emerging Asian economies

October 7, 2025 (IEEFA Asia): A global shortage of gas turbines is likely to exacerbate delays and drive up costs for new gas-fired power projects in Vietnam and the Philippines, according to a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Both countries aim to rapidly expand gas-fired power capacity over the next decade, but major gas turbine manufacturers are reporting extensive production backlogs and advising project developers to plan seven to eight years ahead for turbine procurement.

“Turbine backlogs add to an already lengthy list of regulatory and financial challenges delaying gas-to-power projects in Vietnam and the Philippines,” says Sam Reynolds, the report's author and LNG/Gas Research Lead for IEEFA Asia. “Meanwhile, the rapid expansion of low-cost renewables and storage could ultimately limit the long-term role for gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG).”

Vietnam and the Philippines are unlikely to hit gas-to-power targets

According to the report, the Philippines is unlikely to bring any new LNG-fired power plants online this decade. Although one project in Batangas is set to begin fully operating this year, the country’s other proposed projects, totaling 10.7 gigawatts (GW) of capacity, remain in early development stages and are unlikely to have secured gas turbine orders.

Meanwhile, Vietnam is likely to miss its 2030 targets for domestic gas and LNG-fired power capacity by a combined 25.2GW. By 2030, the country aims to have 22.5GW of LNG-fired power capacity and 14.9GW run on domestically produced gas, up from 1.6GW and 8.3GW, respectively.

Although two proposed projects in Vietnam have disclosed turbine contracts, they still face other major barriers to financial closure, including a lack of power purchase agreements, gas supply agreements, and government guarantees for payment obligations and foreign currency convertibility.

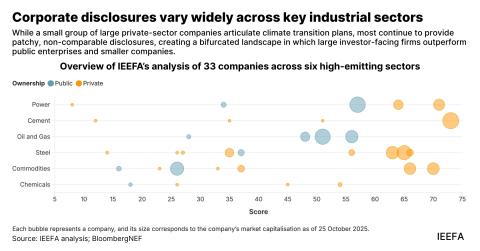

Existing gas-fired power projects in both countries have relied exclusively on turbines from GE Vernova, Siemens Energy, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) — the world’s largest manufacturers that together account for roughly 90% of heavy-duty gas turbine orders since 2015.

Global competition for limited turbine supply

A spike in turbine orders from the United States (US) and the Middle East, combined with supply chain constraints for turbine manufacturing, has created a global shortfall.

Approximately 80GW of turbine orders were placed in 2024, compared to an estimated production capacity among the three largest manufacturers of 30GW. Annual orders are expected to surpass 100GW starting in 2027. The US alone is expected to build 19GW of gas-fired power capacity annually through 2030.

“In recent years, emerging Asian economies relying on imported LNG have had to compete with wealthier buyers in Europe and Northeast Asia for expensive fuel supplies,” says Reynolds. “They find themselves in a similar situation today, only this time it’s for the hardware.”

Estimates for delivery timelines vary, but manufacturers are generally reporting wait times of five years for larger turbines. They are also starting to charge non-refundable reservation fees. For example, one developer reportedly paid GE Vernova USD25 million to reserve a 2030 slot.

Capital costs for new gas projects have nearly tripled, from USD700—1,000 per kilowatt (kW) to about USD2,400/kW today.

Looking ahead

Manufacturers have cautiously announced plans to scale up production capacity, but these efforts are unlikely to reduce near-term costs or delivery timelines due to materials, components, and labor shortages.

Moreover, expanding manufacturing capacity in response to data center and artificial intelligence market hype is risky. Similar to past cycles of overinvestment, manufacturers could be highly exposed if demand does not materialize.

“Emerging Asian economies like Vietnam and the Philippines may be left with few options,” says Reynolds. “Relying on alternative suppliers is challenging given the limited number of established heavy-duty gas turbine producers and the complexity of turbine systems, contracts, and procedures. Using smaller models would result in lower efficiencies and risk dramatic increases in levelized costs.”

Renewables emerge as faster, lower-cost alternatives

Instead, emerging Asian economies are likely to accelerate renewable energy deployment and turn to battery storage technologies for grid balancing. Timelines for solar and wind projects are typically around one year, while LNG-to-power projects can take four years, even before factoring in ongoing turbine shortages and other contractual and regulatory delays.

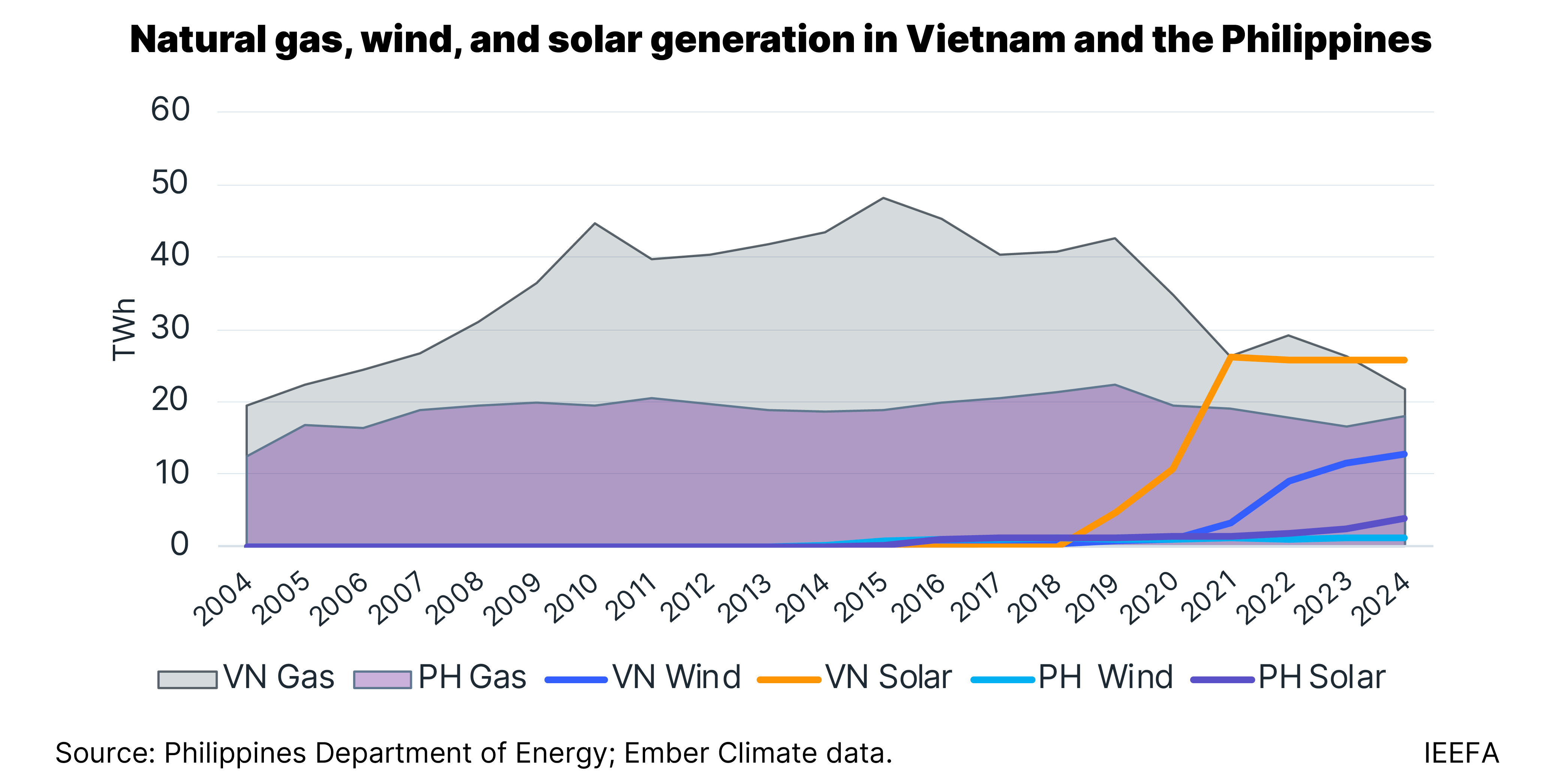

Vietnam’s revised power development plan increased its 2030 solar targets sixfold, after the country’s wind and solar capacity increased from near zero to over 21GW between 2018 and 2023. In the Philippines, solar is now the fastest-growing asset class, and the country has awarded over 13GW of new renewable energy contracts through centralized procurement auctions since 2022. Meanwhile, gas generation in both countries is lower than in 2015.

“Gas turbine shortages make the case for renewable energy in Vietnam and the Philippines even clearer,” says Reynolds. “Every year of delays for gas and LNG-fired power plants means that less gas and LNG will be needed in the long run.”

Read the report: Global gas turbine shortages add to LNG challenges in Vietnam and the Philippines

Author contact: Sam Reynolds ([email protected])

Media contact: Josielyn Manuel ([email protected])