Why Australia’s coal mines are getting bigger

Key Findings

Open-cut or surface mines are the most visible sign of coal mining in Australia, and the country's largest coal mines are getting larger.

Increasing strip ratios – the amount of overlying rock that has to be removed to expose the coal seam – are contributing to higher costs for miners and increased emissions.

A lack of new mine approvals, loopholes in the Safeguard Mechanism and poorly targeted government subsidies are key factors driving this growth, which should be a wake-up call for the Australian government.

Australia’s largest coal mines are getting larger. Mines in New South Wales (NSW) are ramping up production following the state’s recovery from its recent flooding, and there are now six mines that are selling a million tonnes a month.

The problem is that there is a vast gulf between the government’s stated ambitions on climate change and what’s actually happening on the ground.

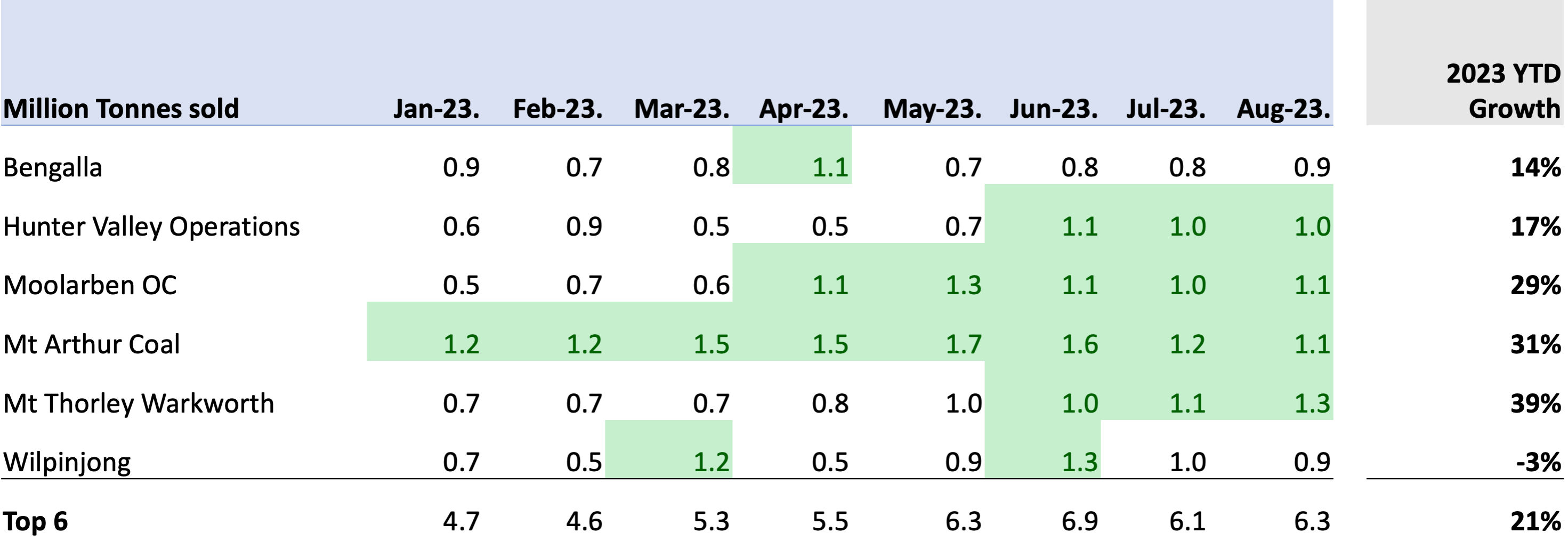

Coal production has ramped up at the largest six mines in NSW. Combined coal sales for the “big six” grew by more than 20% during 2023 to August, compared with a decline of 3% for the remainder of mines in NSW. The six largest mines now make up some 40% of total coal sales in NSW. The recent coal sales from the mega-tonne mines are as shown in the following table:

Source: Coal Services NSW, IEEFA, monthly sales. Cells shaded green represent coal sales of more than one million tonnes in a month. 2023 YTD Growth represents the increase in sales recorded from January to August 2023 compared with the same period in 2022.

All these mines are owned by a range of different coal companies, so what do they share in common? They are all large open-cut coal mines that produce predominantly thermal coal for export markets.

A common explanation for the rise of mega mines is that, with new mine approvals becoming increasingly difficult to obtain, it is easier to ramp up capacity at existing sites. This stems from environmental concerns, lack of miner appetite to invest in new thermal coal projects, and major banks’ lending restrictions on new coal mine developments. Expanding production within the limits of existing approvals may be more straightforward than gaining new approvals or undertaking large investments with lengthy payback periods.

Another factor may be the Government’s light-handed approach to regulating open-cut mine emissions. On 1 July this year, the Commonwealth Government revamped the Safeguard Mechanism, aimed at curbing and reducing emissions from Australia’s largest industrial facilities, including large coal mines. However, a review by Energy & Resource Insights found that six of the top 10 coal mines in Australia – the major open-cut coal mines – have no effective emissions limits under the scheme.

There’s a scale advantage too. The introduction of automated equipment such as autonomous haul trucks makes more sense in the mega mines. Then there’s the investment required to convert the fleet to low-emissions equipment. Open-cut miners report that most of their fugitive emissions are sourced from combustion of diesel. However, the government is subsidising open-cut coal miners through the diesel fuel rebate scheme. This favours the continued operation of large diesel mining equipment and disincentivises switching to zero-emissions equipment.

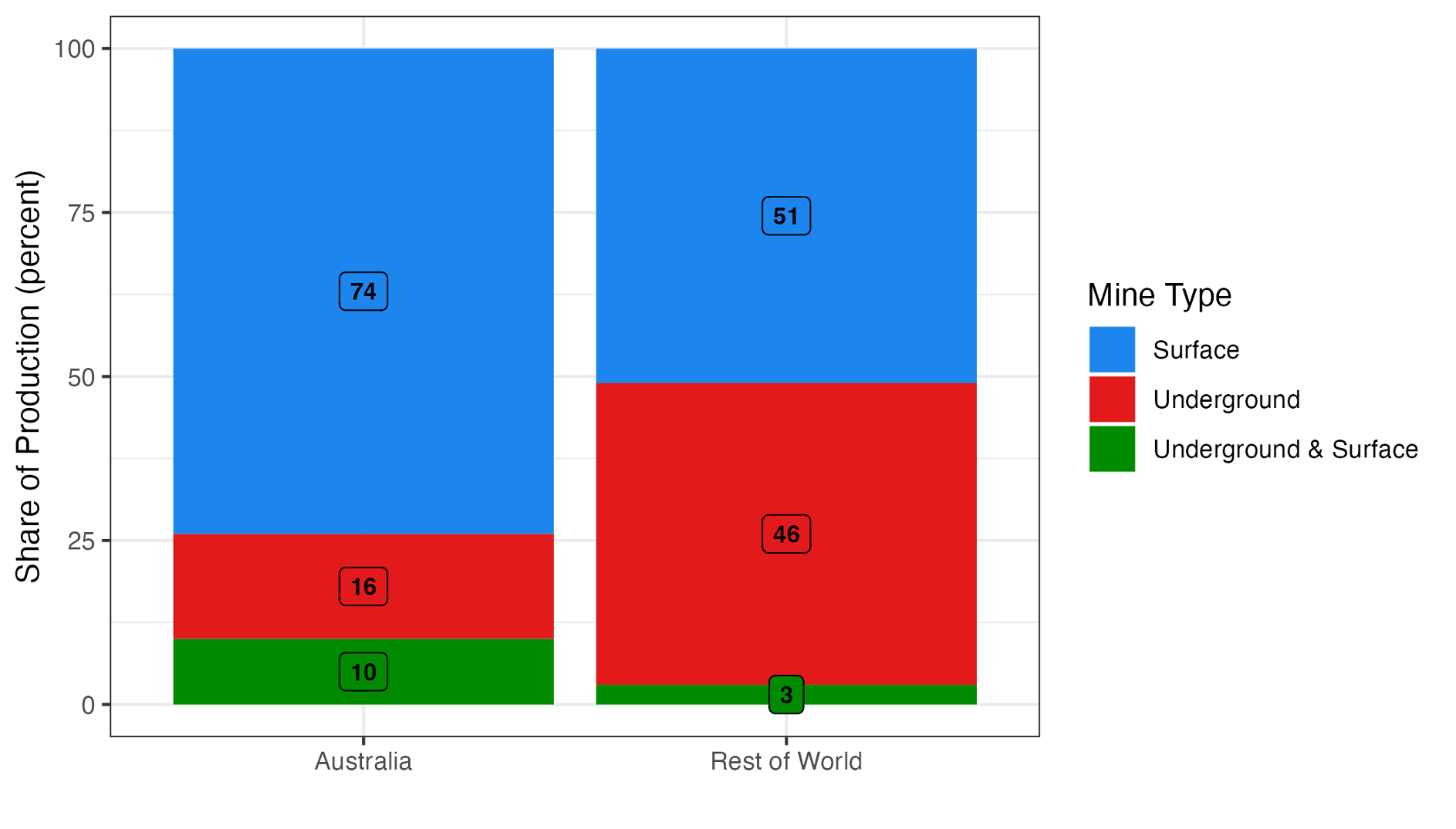

Open-cut or surface coal mines are the most visible sign of coal mining in Australia – and make up most of our coal mine operations. In NSW, open cuts dominate the Hunter Valley coal mining. While there are environmental and community benefits of underground mining, the trend in Australia is currently moving in the other direction. In NSW open cuts now make up 80% of production, increasing from 75% just a few years ago. It’s a similar situation in Queensland, with the top 10 producing mines being open-cut. Data released by Global Energy Monitor (GEM) indicates that Australia is out of step with the rest of the world, which is closer to a 50/50 share of production.

Figure 1 – Coal mine production by type

Source: Global Coal Mine Tracker, GEM, October 2023. IEEFA

Source: Global Coal Mine Tracker, GEM, October 2023. IEEFA

Rising strip ratios

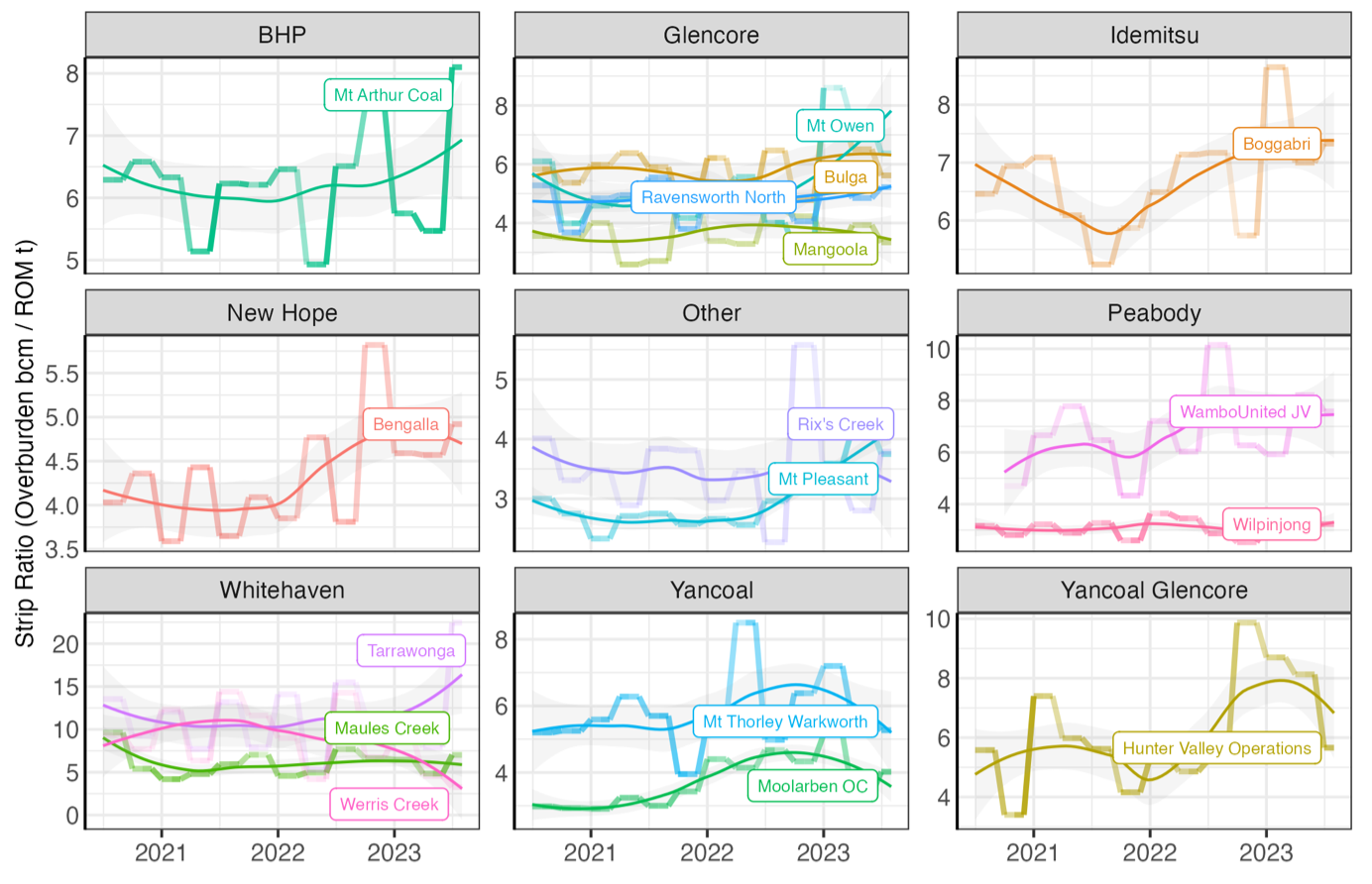

The strip ratio – a measure of an open-cut mine’s implicit efficiency – represents the amount of overlying rock that has to be removed to expose the coal seam available for coal mining. Data from NSW Coal Services has shown a clear trend to increasing strip ratios. Strip ratios have risen at a rate of 6% per year on average in NSW since 2021. The trend for the past three financial years is shown in Figure 2 for the NSW open-cut coal mines.

Figure 2 – Strip ratio trends for NSW open-cut coal mines

Source: NSW Coal Services data, IEEFA. Attributable mine ownership simplified in chart. Actual ownership: Moolarben (Yancoal (95%), Kores Australia Moolarben Coal Pty Limited (5%)); Bengalla (New Hope Group (80%), Taipower (20%)); Mt Thorley Warkworth (Yancoal Australia (80%), POSCO (20%)); Hunter Valley Operations (Yancoal (51%), Glencore (49%)); Wambo United JV (Peabody 50%, Glencore 50%); Ravensworth (Glencore (90%), Itochu (10%)); Boggabri (Idemitsu via Boggabri Coal (80%), Chugoku Electric Power (10%), NS Boggabri (10%)).

While it’s been a slow boil, there is a clear and persistent trend, driven by the depletion of more favourable coal reserves and their replacement with higher-ratio reserves, including deeper and more geologically constrained reserves and/or thinner coal seams.

Implications for the industry and investors

Higher strip ratios affect mining companies’ cost structure and economic viability.

The increased operating expenditure (OpEx) intensity is characterised in Yancoal’s 2023 Half Year Financial Report: “To capitalise on a period of record high coal prices, our mines prioritised coal extraction over pre-strip and overburden removal activities, particularly during 2022.”

Increased capital expenditure (CapEx) intensity can result from the need for additional stripping and mining equipment to move higher volumes of overburden in order to maintain production volumes.

The majority of emissions reported in open-cut coal mining relates to diesel combustion. As strip ratios increase, by definition, more waste rock/overburden has to be removed, resulting in higher emissions intensity from the operation of diesel earthmoving equipment. More overburden also produces more drill and blast activities.

Rising strip ratios in the coming years are likely to exert pressure on the margins of big mines. Whether or not this will contribute to the closure or mothballing of mines is unclear. However, in a given market condition, it is the strip ratio that underpins the ultimate economic limit of these mines.

Newly proposed open-cut mines are also impacted. When Glencore announced in December 2022 that it was shelving what would have been one of Australia’s largest open-cut mines, the Valeria project, it found a convenient excuse by drawing attention to increased Queensland royalties. It was reported that “the decision to abandon the Valeria project was based on global uncertainties and an increase in state royalties”. However, in the final project submission to the Queensland Government, it also stated that the workforce requirement had gone up by nearly one-third “based on the increased strip ratio identified following the exploration drilling programs and update to the geological models”. Such a significant surprise late in the process no doubt affected the investment case.

Implications for government

Given that the Safeguard Mechanism is its key lever to achieve Australia’s legislated emissions reduction target (of 43% below 2005 levels by 2030), you’ve got to wonder if the government has this issue under control.

The reality is that the revised Safeguard Mechanism is actually causing unintended consequences. It is focusing the miners into expanding existing open-cut mines.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2023 Production Gap Report, governments play a central role and “focusing on emissions alone is insufficient… the production of fossil fuels must also decline at a rapid pace”.

According to the UN Secretary-General António Guterres, “Governments are literally doubling down on fossil fuel production; that spells double trouble for people and planet.”

In this light, the Government has a responsibility to act to address the growth of the mega-mines.