Virtual power plants are leveraging Australian consumer investment in rooftop solar

Key Findings

Australia’s rooftop solar uptake drives innovation in distributed energy resources

Rooftop solar, batteries, electric vehicles and smart appliances work as a single conventional, flexible and dispatchable power plant

Payback periods for an average household rooftop system are three to four years and household batteries about eight years

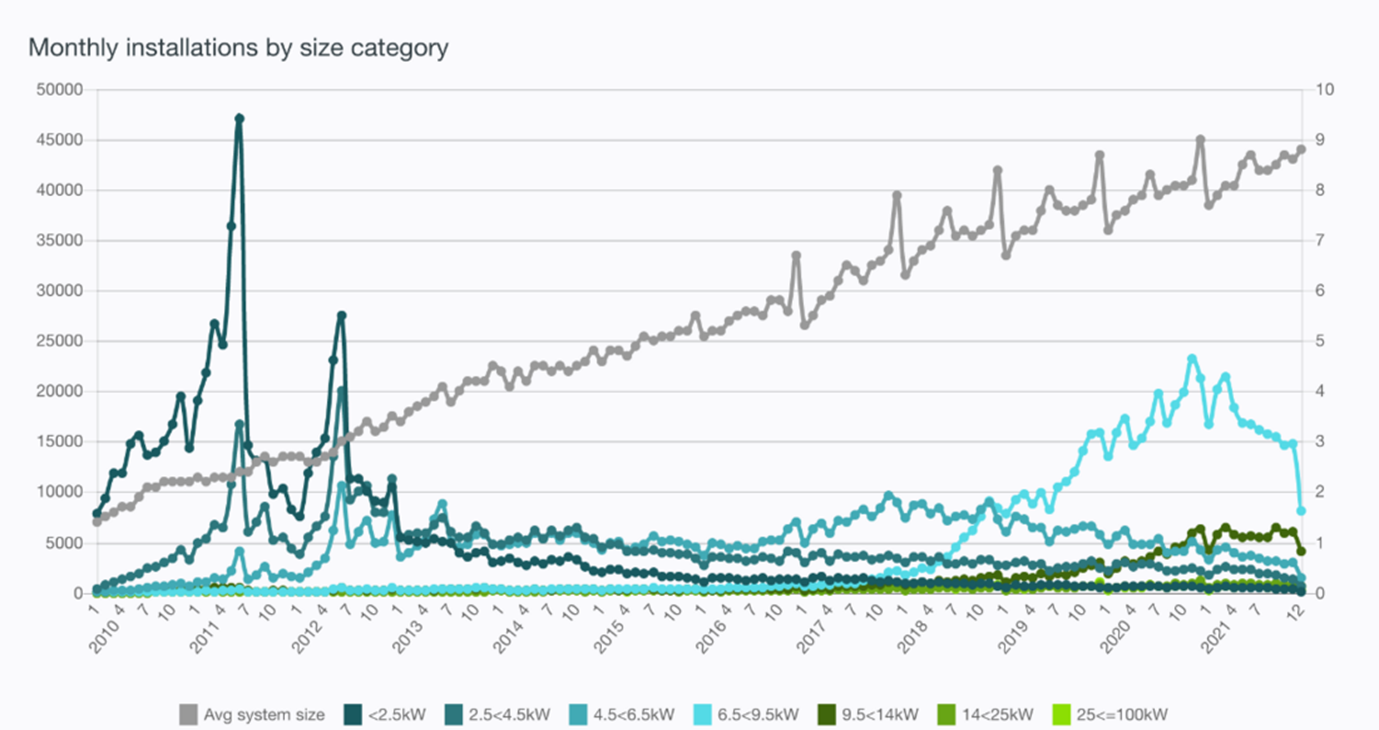

Australia has more than 3 million household rooftop solar systems, which is almost of a third of all households, and installation rates remain high. In 2020 and 2021, 3 gigawatts (GW) of rooftop solar was installed.

There are also thousands of commercial and industrial (C&I) rooftop systems giving a combined total rooftop solar capacity of 17GW at the end of 2021, out of a total solar capacity of 25GW in the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM).

The figure below graphs the installation rates by size over the past 11 years, showing the steady increase in average system size.

Australian PV Installations by Size January 2010 - December 2021 Source: Australian Photovoltaic Institute (APVI)

Payback periods for an average household rooftop system (6-7kW) are currently 3-4 years (after a Federal PV rebate averaging $A2500) and there are several providers of finance and commercial offers where households bear no upfront cost. Household batteries have longer payback periods of about eight years and are also supported by subsidies in some states.

VPP market in early stage of development

A VPP is a network of distributed energy resources – not just rooftop solar, but also batteries, electric vehicles and smart appliances – working as a single power source and aggregated via software to participate in energy markets. The DER are “operated in a coordinated manner so that from the system’s point of view this set behaves as one single conventional, flexible and dispatchable power plant.”

In Australia, VPPs are coordinated in two ways:

- Cloud-based gateway – the inverter (or other DER) has embedded energy management capability, for example, in sonnen and Tesla inverters.

- On-site gateway – a dedicated device that manages DER BTM. In Australia, two aggregation companies have developed these devices, the Reposit smart controller and SwitchDin’s droplet.

On-site gateways are generally able to manage multiple BTM devices, optimising consumption, storage and exports in line with price signals. Some inverters (such as SolarEdge’s Energy Hub inverters) also include these capabilities.

VPPs are forecast to be a major part of the future energy mix in the NEM

Given the extent of rooftop solar in Australia and as the cost of batteries fall, VPPs are forecast to be a major part of the future energy mix in the NEM, which operates on the east coast of Australia and the Western Australian Wholesale Electricity Market (the WEM) which operates in the southern part of Western Australia.

However, the VPP marketplace is still in the early stage of development. IEEFA estimates the NEM’s total household VPP fleet is currently about 300 megawatts (MW). Of that, one of Australia’s largest retailers, Origin Energy has 205MW from over 100,000 connected services.

Trialling VPPs

Australia’s development of VPPs has been supported by a number of trials part-funded by the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA). The most significant was run by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

Participation was open to any technology, although all VPPs in AEMO’s 2021 trial were based on household batteries connected to rooftop solar systems. Approximately 7150 consumers were involved, or about 6% of the estimated 110,000 BTM batteries in the NEM.

The trials had total registered capacity of 31MW (27MW was in South Australia, where the state government gave generous battery subsidies). The 31MW constituted a 3% market share of the NEM’s six contingency Frequency Control and Ancillary Services (FCAS) markets: designed to raise and lower frequency on a fast (six-second), slow (60-second), or delayed (five-minute) basis, of which the six-second markets are the most valuable.

The trials found coordinated batteries could deliver wholesale FCAS services and, potentially, network services, in some cases simultaneously. During the trials, a potential conflict was noted when wholesale prices were high and there was simultaneous need for frequency lower services (provided by batteries discharging). In this circumstance, which both use the discharge of batteries, AEMO modified the optimisation algorithm to ensure priority was given to FCAS services and the stabilisation of the system, despite this causing a reduction in the aggregator’s wholesale market revenue.

The following list shows the revenue earned by participants during the AEMO VPP demonstrations. Only the largest VPP provider, Energy Locals in partnership with Tesla, made substantial revenue from participating in the FCAS markets. Notably, two events provided 49% of the FCAS revenue; a major system disturbance and a separation event where South Australia was islanded from the rest of the NEM.

Retailer/Aggregator (Capacity at Conclusion) FCAS Market Revenue Sept '19-Jan '21

- Energy Locals (16MW) $2,200,000

- AGL (6MW) $99,000

- Simply Energy (4MW) $85,000

- Sonnen (1MW) $2,000

- Shine Hub (1MW) $180

- Energy Locals (Solar SG/Members Energy) (1MW x2) $0

- Hydro Tasmania (1MW) $0

This set of trials is reflective of a future where VPP revenue is likely to be gained during infrequent events, rather than daily peaks. More work needs to be done to understand the potential nature of VPP revenues, especially as market dynamics change with the inevitable transition to variable renewable energy.

Revenue from wholesale market participation was not recorded. The VPPs only participated in the wholesale market when prices were over $300/MWh and even then, participation was limited to three of the seven participants (because the others were too small) and the most reactive VPP only responded to high prices around 39% of the time.

VPP products

Today, there are about 20 commercially-available VPP products in the NEM. For consumers, these offers are in a variety of forms which are difficult to compare.

There are fixed financial rewards/offers such as quarterly/monthly payments for battery access (e.g. Origin provides a $20 credit on household electricity bills each month for five years). Reposit offers a ‘No bills for 5 years’ guarantee if the household purchases a Reposit-controlled solar and battery system. And there’s an alternative option of fixed monthly bills, such as sonnen’s VPP in partnership with Energy Locals, which is $49-$69/month depending on household demand size.

There are also variable financial (or other) rewards such as higher feed-in tariffs. Discover Energy pays 45c/kWh for the first 300kWh/quarter, 25c/kWh for the next 300kWh/quarter, then 9c/kWh after that for all NEM states other than Victoria. Origin’s ‘Spike’ voluntary demand response program (run by Ohm Connect) offers consumer savings of up to $250/year. There are also ‘buy now, pay later’ VPP options with fixed tariffs such as EnergyAustralia’s ‘On’ product which is electricity at 26.9c/kWh plus a daily supply charge of $0.73 for seven years.

As a rough benchmark, the average household electricity cost reduction from VPP participation - where an aggregator has unlimited access to a household battery, is about $200/year. This VPP revenue is far less than the savings customers gain from batteries storing BTM solar generation and avoiding grid imports.

These low levels of financial reward for consumers suggest that revenue from VPPs is currently low.

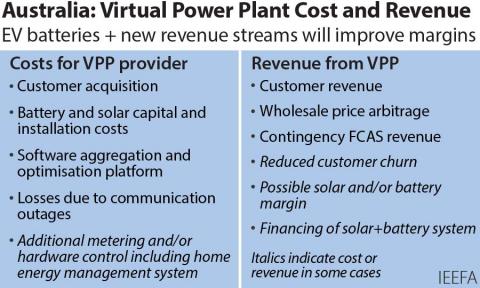

On the cost side, there are major costs in the creation of software aggregation platforms, and in any associated hardware to aggregate the DER and optimise its use, including what services to provide to the grid what time to provide them.

Current margins for VPP operators are expected to be thin

IEEFA notes that given the low revenue and cost of VPP establishment, current margins for VPP operators are expected to be thin.

In February 2022, Origin announced plans to increase its in-house VPP from 205MW to 2000MW within four years. To its investors, Origin stated that its in-house VPP “creates lower churn, deeper engagement and seeks to fulfill customers’ expectations for lower costs, decarbonisation and energy autonomy.” Clearly Origin understands the opportunities of VPPs, especially in leveraging consumers’ assets BTM to speed up decarbonisation of the energy market.

As with Origin, the many aggregators and retailers already providing VPP offers to consumers are likely seeing the future opportunity of greater DER capacity, including increased revenue and relatively low costs compared with the installation of large-scale wind, solar and storage.

This article first appeared in Cigre’s digital magazine Electra