SFDR’s early-life crisis presents an opportunity to level the playing field

Download Full Report

Key Findings

SFDR is failing its transparency goals, with capital flow data adding weight to a growing recognition of issues. In reaction, the recent consultation seeks opinion on options for course correction.

Two competing approaches for reshaping SFDR have emerged, but only by replacing the current article system with a labelling scheme applied uniformly to all products can we redress current imbalance.

Increased compliance burden on managers should be tempered by retooling existing processes, significant overlap with similar UK based proposals and development of the European Single Access Point.

National regulators need to prepare for increased supervisory demands, and asset managers should already be looking to tighten practices, particularly as they relate to current Article 8 products.

Executive Summary

A continually evolving regulatory landscape in Europe now includes a broad-ranging consultation on the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), opening the door for a fundamental reworking of the current system. This latest consultation comes in reaction to growing industry concern that SFDR in its current format is not achieving its transparency goals. A poll conducted during the European Commission’s open forum on the consultation showed that almost two-thirds of respondents believe SFDR disclosures have created more confusion than clarity, raising the risk of greenwashing.

Problems with SFDR stem from a disconnect between its intended use as a system for identifying appropriate fund disclosure levels and its adoption as a de-facto environmental, social and governance (ESG) labelling system used by managers to signal the sustainability ambition of products. Vague definitions and managerial agency over the SFDR categorisation process may have been appropriate for a disclosure regime, designed to accommodate various investment approaches, but have ultimately led to a damaging lack of consistency in application. This is particularly true of Article 8 funds where sustainability ambition varies widely. This in turn presents a real headache for asset owners trying to allocate capital to more sustainable products, particularly at the retail end of the market.

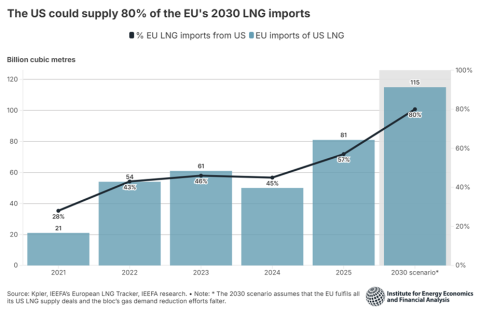

Stakeholder sentiment on this issue is further backed up by evidence from recent capital flow data. Article 8 products (which promote environmental or social characteristics) have seen outflows in both of the last two quarters, even as the reverse has been true of sustainably ambivalent Article 6 counterparts. More tellingly however, redemptions have disproportionally affected Article 8 funds with no commitment to sustainable investments, which represent around two-thirds of recent outflows, despite only accounting for one-third of the universe in terms of size. Additionally, demand for less sustainably ambiguous Article 9 products (which have sustainability as an explicit objective) remains intact. Perhaps then, reports of the death of sustainable investing have been somewhat exaggerated, but there is little doubt that funds claiming some level of sustainability ambition need clear qualifying criteria setting out.

Based on the consultation, there seem to be two trains of thought as to the future shape of SFDR:

- Keep the SFDR article definitions as they are, but apply minimum standards for Articles 8

and 9, potentially with labels then built upon them. - Do away with existing SFDR article levels and switch to a system of labelling.

The first option ignores a significant imbalance in the current regime whereby the most demanding disclosure requirements are targeted at sustainably led products (Articles 8 and 9), making investing on this basis more burdensome, and more importantly, reducing comparability with Article 6 funds. This serves to mask the negative impacts of products with no sustainability ambition.

The second option, and IEEFA’s preferred approach, would involve applying sustainability reporting requirements consistently to all funds, logically removing the need for article distinctions. IEEFA envisages that any fund voluntarily seeking a label must adopt minimum, label-specific standards that are decided centrally as a safeguard. Process-specific standards should then be additionally applied to tighten criteria where it is appropriate. In order to address concerns around the stymying of innovation, managers should be able to set their own criteria at the process level, so long as it is ratified and verifiable by a third party.

IEEFA acknowledges further industry concern regarding the potential for increased compliance burden and cost to managers, but any impact should be tempered by a few factors:

- Significant overlap with similar proposals recently presented by the Financial Conduct Authority (UK).

- The retooling of existing operational processes.

- Development of the European Single Access Point.

- Potential for future streamlining of mandatory universal reporting metrics.

In the advent of labelling, where third-party verification is required, improvements in the current supervisory environment must also follow. The burden on national competent authorities will also undoubtedly increase, and consideration should be given to the development and adoption of artificial intelligence systems to assist in this process.

Finally, although we cannot yet predict the outcome of this latest consultation, the onus should already be on asset managers to get ahead of the curve and tighten certain practices voluntarily. For example, managers that stubbornly refuse to adopt any form of minimum standards in their Article 8 products will appear weak in terms of their ESG commitments. Indeed, as we have seen in the capital flow data, such managers are already being punished for adopting this stance as flows disproportionately desert funds without minimum sustainable investment thresholds. Be it through regulatory catch-up or market forces, the message to asset managers should be clear―jump or be pushed.