New coalmines could deliver zero royalties and a methane headache for Queensland

Key Findings

The Queensland government is banking heavily on coking coal in the hope of extracting big royalties, with recent production figures suggesting a deceptively positive outlook for the sector.

However, recent earnings results and the Resources and Energy Quarterly forecasts point to worsening market conditions, which raise questions about the economic case for multiple mine expansions in progress.

New mine expansions cast doubt on the government’s plans for emissions reduction.

Queensland produces 90% of Australia’s metallurgical coal exports, and coal is one of the state’s largest economic contributors. The Queensland government has a target of 75% emissions reduction by 2035 and, while statewide emissions are down 29% to 2021, the state’s coalmine fugitive emissions have risen 36% from the 2005 baseline.

Some companies are contemplating building new largescale greenfield coalmines in coming years. The expectation is that these developments will boost the royalty income for the state government. But recent events shed some doubt on it.

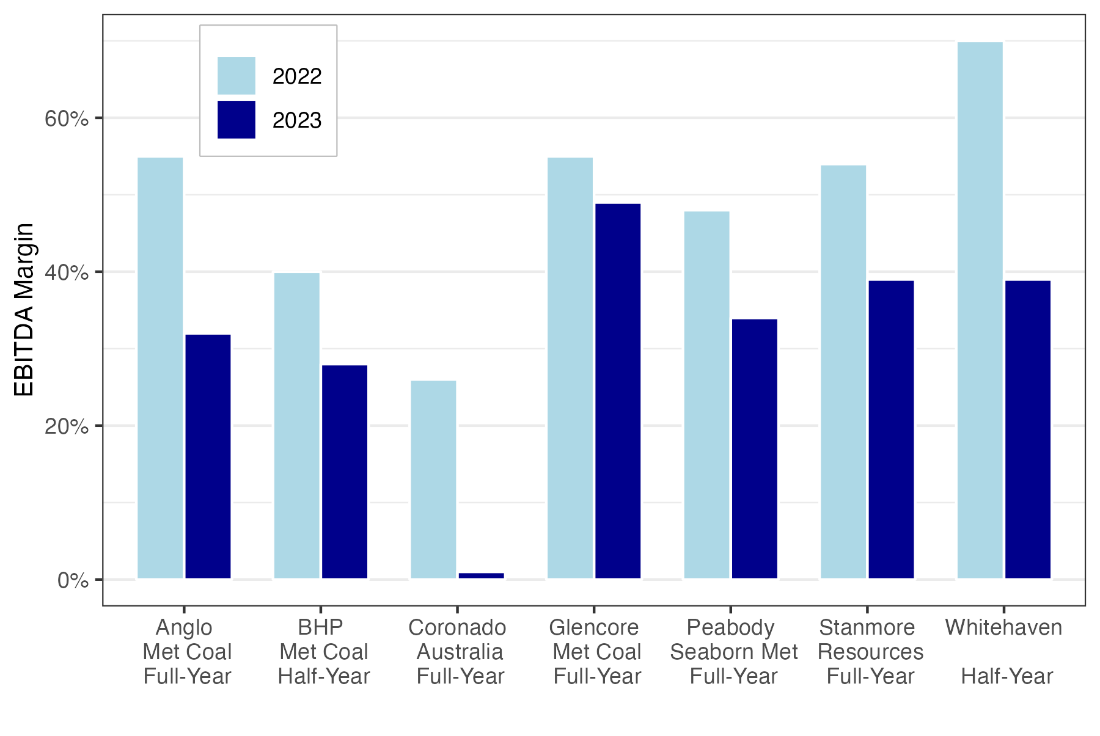

The EBITDA margins reported by key metallurgical coal producers highlight the recent decline in profitability across the industry.

EBITDA Margins from key Qld metallurgical coal producers

Source: December 2023 company financial results, IEEFA

The Office of the Chief Economist’s most recent Resources and Energy Quarterly forecasts further falls in earnings for met coal exporters in coming years, stating: “Further price falls could potentially affect the outlook for new projects.”

Queensland has multiple greenfield open-cut coalmine projects, such as Olive Downs, Winchester South, Blackwater South, Baralaba South and Vulcan South. They all plan to produce “lower grade” coking coals, such as semi-hard coking coal and PCI (pulverised coal for injection into blast furnaces). These varieties represent just 20% of Queensland exports at 42 million tonnes (Mt) in FY 2023. Yet the combined annual production is approaching 40Mt, including include some by-product thermal coal.

BHP has decided to exit this congested and low-yielding coking coal market through recent asset sales, and instead concentrate on premium coking coal.

Queensland’s coalmine fugitive emissions (methane converted to CO2 equivalent) were reported to be 16.5Mt in 2021 – the latest year reported. The reporting estimating factor for open-cut coal mine emissions (method 1) has since been increased by 35%, signalling higher emissions than when greenfield projects were approved. Existing mines will also have their fugitive emissions recast with the higher estimating factor or potentially new stricter reporting methods.

These open-cut greenfield mines are not required to pre-drain methane from their operations. Approvals are on the basis that they are unabated – that is they do not require abatement of methane emissions. Governments require the large mines to develop “detailed emissions management plans”, yet some have dodged the concept of pre-drainage of opencut mines – arguing that it is too difficult and this methane only accounts for a fraction of global emissions. Instead, they propose business as usual decarbonisation strategies such as “ensuring equipment is operated efficiently and maintained to manufacturers’ standards.” Fugitive emissions reductions, if required can be handled by purchasing carbon offsets.

Coalmine approvals also promise governments economic benefits and a steady stream of royalties. For example, the Baralaba South coal project’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) promises, “$62.6 million per annum to the Queensland Government, (mainly royalties) and $68.7 million to the Australian Government per annum, (tax)”. For the Olive Downs project, the owners promised “up to $10.2 billion in royalties for the Queensland government”.

Yet some coalmines in Queensland in the past year have been placed into care and maintenance (Bluff mine) or administration (Wilkie Creek) due to declining market conditions.

The economics are fragile. The Bluff mine was a similar strip-ratio open-cut mine producing the same coal type – yet actual operating costs were 80% higher during its final six months. Similar cost pressures and increases have been felt across the industry over the past few years, typically by 50%. Swapping out the unit cost assumption made by the Baralaba South proponents with the actual unit cost of the Bluff mine or with typical industry cost increases experienced, would recast Baralaba South as loss making. There would be no royalty payments or taxes paid.

This has been the case with Bluff mine. During 2023 the owner deferred payment of royalties to the state government and reported nil company tax.

Not only are the risks of investing in new mines increasing as margins decline, the risks to the government from more mothballed mines and deferred or cancelled royalties is increasing.

Investments in methane abatement that have been considered by miners are generally commercially unattractive and unviable. It is just one of many capital expenditures competing for miner’s attention. Miners have established a pattern of returning funds to shareholders, paying large dividends and buying back shares. Funding for acquisitions or mine expansions is made more difficult as traditional lenders transition away from fossil fuel investments. Methane abatement investments compete with other decarbonisation initiatives for remaining capital. Competition for capital will only intensify as earnings decline.

The Queensland government has established a $520 million Low Emissions Investment Partnerships (LEIP) program to fund methane abatement activities in metallurgical coalmining. This will supplement the capital investment required for methane pre-drainage.

In the absence of government stimulus, the industry has been making some inroads. Some miners are reporting that early methane abatement measures are putting them on track to meet their emissions reductions targets for 2030.

- For Coronado, at Curragh mine, gas pre-drainage trials at the open-cut mine are under way. Gas use cases are being examined, such as converting a haul truck to run on compressed natural gas. This is just one way it could counter the high-cost inflationary pressures due to elevated diesel prices.

- At Anglo, installing methane abatement at its three Australian operations has led to

a 19% reduction in methane emissions in one year. “Improvements in the management

of methane in our steelmaking coal business have made the largest contribution to this reduction in emissions”. The Anglo Sustainability report states: “We have invested significantly, c.$100 million per annum, in methane pre-drainage infrastructure at our underground steelmaking coal operations. In 2023, across these operations, we abated approximately 60% of methane emissions, including 5.3 Mt CO2e emissions through the capture and delivery of methane to gas-fired power stations.”

Meanwhile, miners are working to hone the business case for methane abatement projects. Technical advancements must drive down costs and markets be developed for the gas collected. What’s more, pre-drainage needs to be planned well ahead of the mining sequence.

With government support, the positive economic potential of methane abatement could be achieved.

Methane abatement in coalmining needs to become the rule not the exception. Isolated success cases should be promoted and adopted across the industry. Planning needs to start now to have an impact on the 2030 emissions targets. Beyond that, making methane abatement measures part of all new coalmine developments needs to be considered. Otherwise, the large-scale roll-out of new, unabated open-cut mines will place Queensland’s 2035 target of 75% emissions reduction at risk.

First published on The Fifth Estate.