Key Findings

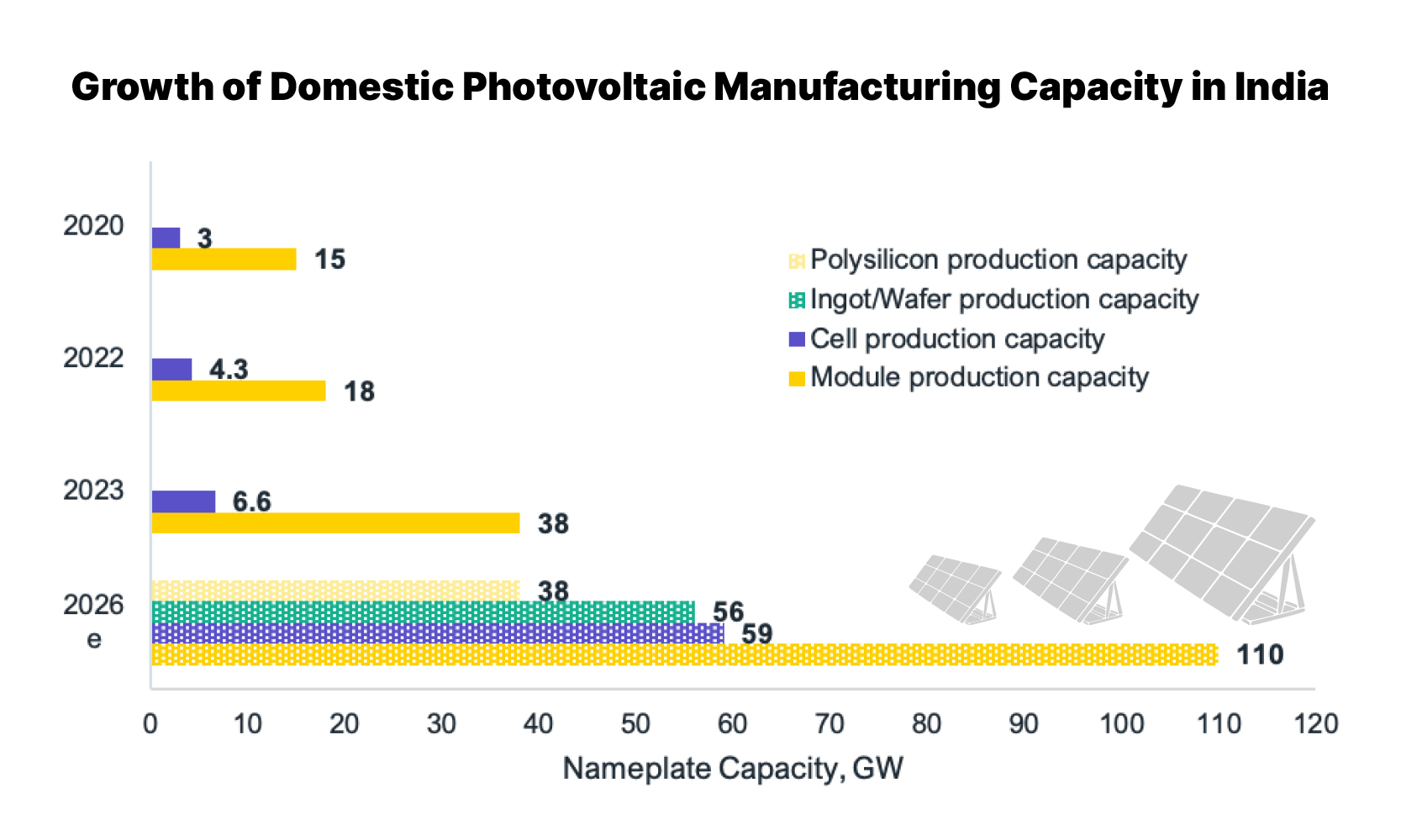

Around 110 gigawatts (GW) of photovoltaic (PV) module manufacturing capacity is set to come online in India by the financial year (FY) 2026, which will make the country self-sufficient.

India's cumulative module manufacturing nameplate capacity more than doubled from 18GW in March 2022 to 38GW in March 2023.

The two tranches of the production-linked incentive scheme will help add 51.6GW of module capacity and at least 27.4GW of integrated ‘polysilicon-to-module’ capacity in India in the next three to four years.

India’s nameplate manufacturing capacity for solar photovoltaic (PV) modules will likely reach 110 gigawatts (GW) by 2026. Upon reaching that mark, the country would attain self-sufficiency for its solar PV module demand. India should then focus on expanding its reach in other global markets and offer its PV products as a viable alternative to China in terms of quality and price. Favourable policies, particularly the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme have helped PV manufacturing grow rapidly in the last two to three years, with the nameplate capacity for both cells and modules more than doubling. Yet, overreliance on imports for upstream components, muted interest among domestic consumers for locally made PV products and lack of skilled manpower to install and operate the high-tech machinery is holding back the full potential of the industry. Policy stability must continue to sustain investor confidence in the PV manufacturing sector.

Since the early 2010s, the world has largely depended on China for its photovoltaic (PV) equipment requirements. The huge concentration of the entire PV value chain in one country poses a potential risk to other countries. It leaves them susceptible to localised supply chain shocks and other challenges.

In recent years, PV importers, such as India, the United States of America (the U.S.) and Europe, have enacted several measures to limit the dependence on China and support local PV manufacturing.

India introduced a safeguard duty (SGD) in 2018, while the U.S. instated anti-dumping duty (ADD) on Chinese PV imports. More recently, the U.S. issued its Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides an extensive production-linked incentive plan to support PV manufacturing.

In India, the government has put in place several tariff (basic customs duty (BCD)) and non-tariff (Approved List of Models and Manufacturers (ALMM)) barriers to PV imports. In addition, the government included solar PV manufacturing in its production-linked incentive scheme (PLI) scheme, with a total outlay of approximately US$3.2 billion spread over two tranches.

Echoing the favourable policy environment created by the Indian government, PV manufacturing has grown rapidly in the last two to three years. Between 2020 and 2023, the nameplate capacity for both cells and modules more than doubled in India. We estimate that the operational capacity for both cells and modules is between 50-60% for most manufacturers.

Source: JMK Research

By 2026, India will likely reach the 110 gigawatts (GW) mark in solar module manufacturing nameplate capacity. India will also have a notable presence in all upstream components of PV manufacturing, such as cells, ingots/wafers and polysilicon.

The PLI scheme is one of the primary catalysts spurring the growth of the entire PV manufacturing ecosystem in India. Besides the augmentation of infrastructure in all stages of PV manufacturing, from polysilicon to modules, it will also lead to the simultaneous development of an ancillary market. Based on the result of both tranches of PLI, the scheme will lead to the direct augmentation of 51.6GW of module capacity and at least 27.4GW of integrated polysilicon-to-module capacity in India.

PV technology is continuously evolving. Poly-crystalline, which was the mainstay just a few years back, is already obsolete. Currently, designs for all existing and proposed manufacturing lines are for mono-passivation emitter rear contact cells (PERC). This continuous technology shift highlights the need for manufacturers to plan carefully while designing their PV lines to accommodate all future scenarios. Hence, all current mono-PERC line designs can easily upgrade to other upcoming technologies, such as Heterojunction technology (HJT) or Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact (TOPCon).

Furthermore, all major PV importers also aim for a “China+1” strategy for their PV sourcing requirements. In addition to already having the second largest module manufacturing capacity, India has significant expansion plans in the next two to three years. Hence, Indian tier-1 manufacturers have a huge interest and demand from abroad for their products. Compared to the financial year (FY) 2022, Indian PV exports (by value) have already risen by more than 5x in FY2023.

However, despite the growth and demand from other exports market, the Indian PV manufacturing sector is still facing headwinds. These include sustained reliance on imports, especially for upstream components (polysilicon and ingots/wafers), ancillaries and PV machinery. Although the quality of all tier-1 Indian manufacturers is comparable to global standards, the manufacturers have complained that the domestic consumer base is largely hesitant towards Indian PV products. In addition, the lack of skilled manpower to install and operate the high-tech machinery, especially for cells and other upstream components, is also an ongoing challenge.

The future of the Indian PV manufacturing sector is bright. Upon attaining self-sufficiency in the next two to three years, India must focus on expanding its reach in other global markets and offer its PV products as a viable alternative to China in terms of quality and price. In the meantime, policy stability is a must for sustaining investor confidence in the market.