IEEFA Update: South African coal miners must get used to low export volumes

A week before Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe talked up the future of South African coal, Richards Bay Coal Terminal (RBCT) revealed its coal export volumes in 2021 were the lowest in 25 years.

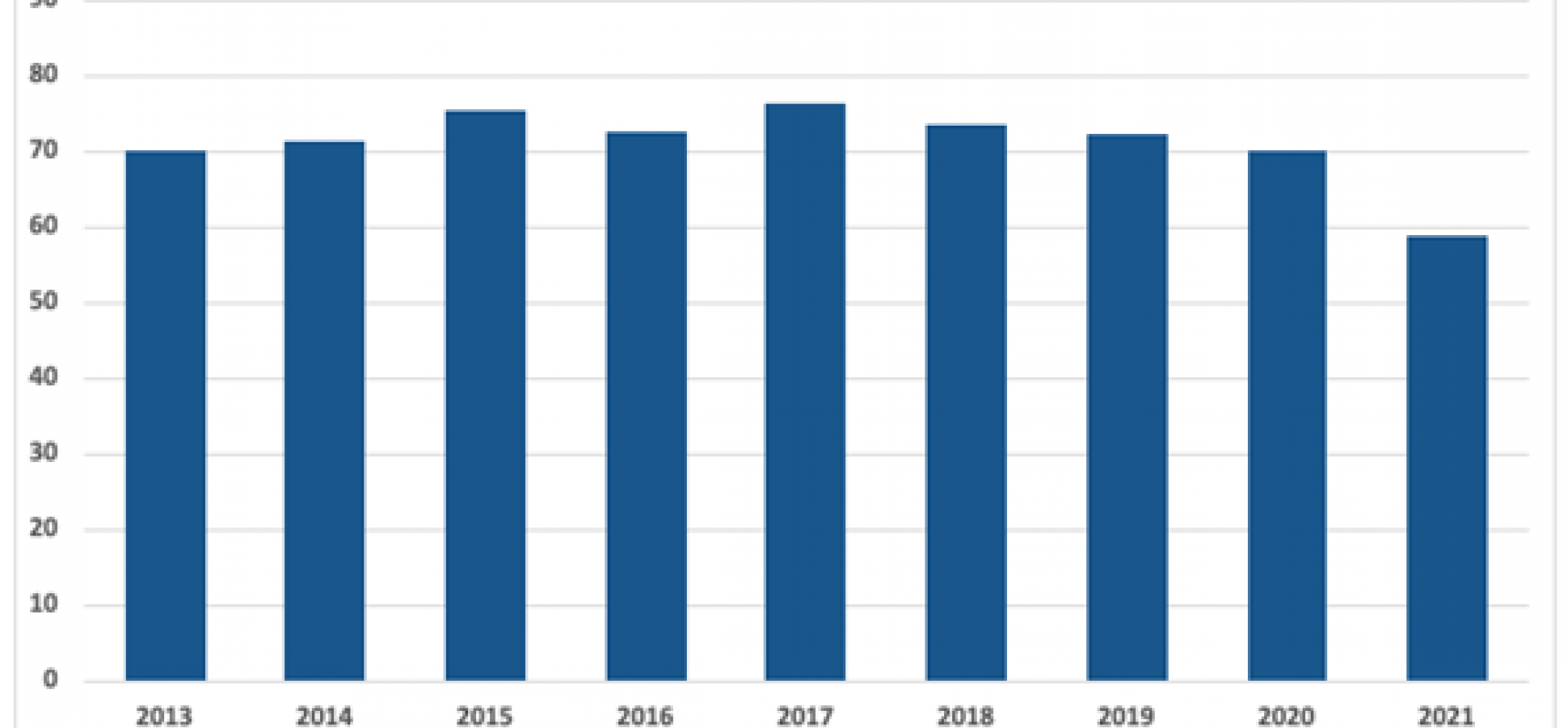

Total coal exports were under 59 million tonnes (Mt) – the lowest since 1996, down 16% on the 2020 total and 24% below RBCT’s 2021 budget. The key reason for this significant downturn was a range of security and operational issues on the rail lines connecting coal mines to the terminal.

Figure 1: RBCT Coal Exports (million tonnes)

Source: Richards Bay Coal Terminal

The logistics issues meant that South African exporters weren’t able to take advantage of high thermal coal prices to the extent they would have hoped.

High prices that followed China’s ban on coal imports from Australia, and higher demand amid economic recovery in 2021, may make it seem as if thermal coal is enjoying a resurgence. However, at this stage of the global energy transition, high coal prices – along with record high LNG prices – make switching to renewable energy look even cheaper.

Indonesia’s recent restriction on coal exports has not only kept prices high into 2022 but also has made coal supply less reliable, likely destroying long-term demand even faster.

The 2021 decline can be ascribed to domestic rail issues, though the South African mining industry may need to accept such volumes as permanently lower international demand is well on its way.

More than 86% of RBCT’s 2021 coal exports went to just three countries – India, Pakistan and China. The great risk of becoming increasingly reliant on so few major importers becomes even more apparent on viewing developments in these countries.

South Africa’s opportunity to export coal to China resulted from the latter’s ongoing ban on imports from Australia. That opportunity is likely to be short-lived.

China’s seaborne thermal coal imports are likely to fall substantially

A new study on Chinese coal demand finds that its seaborne thermal coal imports are likely to “fall substantially” over the coming decade, by as much as 96Mt by 2025 and 124Mt by 2030.

This decline is being driven by coal transport infrastructure development enabling greater reliance on domestic coal, as well as accelerating decarbonisation and the prospect of further overland imports from Mongolia.

A significant decline in Chinese thermal coal imports would have a major impact on Indonesia ‒ the world’s largest thermal coal exporter and China’s biggest supplier of imported coal ‒ which would then need to increase focus on other markets.

Indonesia, already the largest thermal coal exporter to India, may increase competition with South African coal there if it starts to lose its Chinese market.

Meanwhile, Pakistan has long since moved away from further reliance on imported thermal coal and has cancelled several plants that were intended to have been fuelled by imports. Other coal power proposals have had their plans changed to use domestic rather than imported coal as Pakistan has become more focused on indigenisation of power supply.

Existing Pakistan power plants fuelled by imported coal are reportedly at risk of default following the rise in international coal prices.

Given coal power trends in developing Asia, it can be of no surprise then that major South African miners, such as Exxaro, are planning to diversify away from coal.

Exxaro has rightly identified that the “growth in disruptive technology in the energy sector has potential to displace our business in the medium to long term”. As a result, it is planning significant growth in its renewable energy business as well as a diversification into minerals such as manganese, copper and bauxite – products for which it foresees high demand in a new energy world.

Exxaro is aiming for its renewable energy and new minerals businesses to contribute more earnings combined than the coal business by 2030.

No surprise, major South African miners plan to diversify away from coal

Other South African coal miners are likely to follow Exxaro’s lead. Wescoal is proposing a name change to reflect its more diversified outlook. Having “coal” in the name is becoming increasingly inconvenient as more financial institutions move away from coal lending.

Not all coal miners are taking this route. The more export-focused Thungela Resources is retaining its “single-commodity focus on thermal coal in South Africa”, in the apparent belief that disruptive energy technology will not take significant effect in India, China and Pakistan.

Thungela also identifies Bangladesh and Sri Lanka as key coal demand growth markets over the rest of the decade. Bangladesh cancelled 10 coal power projects in 2021. Sri Lanka – which has borrowed billions of dollars from China for infrastructure projects including coal-fired power – is now on the brink of default.

However, Thungela accepts that South African coal exports are set for significant decline, citing a Wood Mackenzie forecast that volumes will drop to 54mtpa by 2030 and 49mtpa by 2035.

Even “coal fundamentalist” Gwede Mantashe accepts that global coal use is set for decline. The minister’s plan to support domestic coal power’s future seems to be based on the type of “low-emission technologies” that make it even more expensive relative to renewables.

With coal already expensive and unreliable, this idea seems unlikely to catch on across developing Asia. South African’s know more than anyone about the high expense and low reliability of coal-fired power.

Given the energy technology outlook in the developing nations that make up South Africa’s main and potential export markets, the risk is now that coal’s global decline will happen faster than the coal industry and its supporters believe.

RBCT’s coal export volumes have dropped every year since 2017. For 2022, the terminal is targeting 70Mt of exports, 7Mt below its missed 2021 budget. In the near future, RBCT will likely need to lower its expect

This article was first published in Business Day.

Related articles

IEEFA India: Endgame for new coal power projects?

IEEFA Update: How Indonesia’s coal export ban could impact India