We’ve published a report today noting that while India has undergone an admirable energy-policy shift over the past few years, it is clinging unwisely to plans to build two costly coal-fired Ultra Mega Power Plants.

Our report—“India’s Questionable Ultra Mega Power Plans”— details how these UMPP projects stand in jarring contrast to better-advised initiatives that include a huge renewable-generation expansion program that aims to increase renewable capacity to 175 gigawatts (GW) by 2022. This program has shown much promise, with India’s total installed solar capacity almost doubling to 7GW in the year to March 2016 and with prices of solar electricity declining by more than 65% since 2010.

Other key aspects of India’s electricity-sector transformation include increasing domestic coal production to 1,500 Mtpa by 2022—a shift meant to eliminate thermal coal imports altogether— and initiatives aimed at containing demand growth through efficiency and grid-improvement programs and increasing the utilisation of existing power plants while shutting older, inefficient plants.

An important moment in the overall electricity sector transformation occurred in June 2016, when it was reported that the Indian Power Ministry had proposed scrapping plans for four coal-fired Ultra Mega Power Plants (UMPPs), in Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Odisha. This was the first such cancellation notice since a UMPP development policy was first proposed in 2005/06 and serves as a clear acknowledgement of multiple difficulties associated with the development of large-scale coal power plants.

The cancellation of these UMPPs also underlines a policy shift toward long-term energy security through the development of domestic coal-mining capacity and the cessation of thermal coal imports.

Nonetheless, and despite the recent major changes in India’s energy policy, the government has gone ahead with the bidding process for two UMPPs, at Bhedabahal, Odisha and Cheyyur, Tamil Nadu. Private investors pulled out of both projects in 2014/15 owing in part to doubts about bidding restrictions imposed by the Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer (DBFOT) model. Another major issue with the bidding guidelines: Limitations on how much developers can pass on increases in fuel costs, exposing investors to fuel-price and exchange-rate risk.

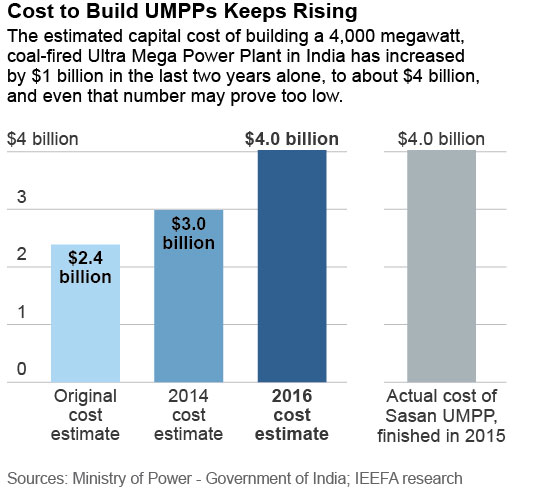

Almost by definition, UMPPs are delayed by approval and construction complications. One clear impact of these delays is on the cost of building these plants. One result of such delays: higher capital costs, which make such project even less viable and increase the risk of these projects becoming stranded assets.

Other hurdles to the viability of UMPPs in India: a doubling of coal taxes three times in the past four years and the overleveraged condition of the Indian electricity sector in generation, a situation combined with a high amount of stress in the Indian banking sector that makes it difficult for proposed UMPPs to raise debt financing.

While recently revised guidelines for the UMPPs address some roadblocks that private bidders faced in raising finance for the projects, important questions remain. Land-acquisition rules for the projects are ambiguous, a tangle of litigation promises further delays, and likely tariffs required on UMPP electricity would drive electricity prices up. Further, a significantly improved power supply scenario in Tamil Nadu has reduced the need for a project like Cheyyur UMPP.

IEEFA’s research suggests that electricity consumers would be better served by an improvement in the finances of Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Company and a focus on eliminating Aggregate Technical and Commercial losses rather than building more power generating capacity. An additional core problem with UMPPs like Cheyyur: reliance on outdated supercritical technology.

Against the backdrop of research that shows the imprudence of expanding coal-fired electricity generation, India’s impressive solar expansion has been accompanied by impressive price declines. The required tariff for solar power has dropped recently to Rs 4.4/kWh (~US$ cents 6.5) from Rs 12.5/kWh (~US$ cents 19.0) –a 65% decline. The cost of solar power has plunged in other parts of the world as well, with records being set in countries that include Dubai, Mexico and Peru.

IEEFA notes that the greatest advantage in solar power is its deflationary nature.

Because the operating costs of a solar power plant are very small (sunshine is free), overall costs remain flat across the life of a project. Fossil-fuel-based power plants, by contrast, are saddled with perennial fuel costs that can increase each year and that are prone to inflation.

Electricity from some existing coal-fired plants in India today is more expensive than solar power. As time goes by, more and more coal-fired plants in India will become costlier to operate than solar-powered sources.

Considering all these issues, IEEFA recommends that India seriously reconsider its UMPP project.

Jai Sharda is an IEEFA Bengaluru-based energy-markets consultant and managing partner of Equitorials.

RELATED POSTS

IEEFA South Asia: A Simple Way to Ease Bangladesh’s Energy Crisis—Import Electricity From India

A Step Backward for Bangladesh

Reliance Power, Indian Electricity Behemoth, Has Turned Toward Renewables

Cheyyur UMPP: Financial Plan Will Make Electricity Unaffordable