IEEFA: The Energy Security Board’s dubious modelling

Key Findings

The so-called benefits of a capacity payment are based on a model that doesn’t actually model a capacity payment.

The claimed $1.3 billion saving flowing to consumers from the capacity payment isn’t actually a saving on their electricity bills.

Energy Ministers are being told to implement a radical change to the national electricity market, forcing consumers to pay conventional generators a guaranteed income based on a consumer savings figure plucked out of thin air, which market information from just the last six months shows is not true.

Australia’s Energy Minister Angus Taylor has been keenly promoting to media outlets that consumers will save $1.3 billion from a proposal that will require those consumers to pay conventional power generators not just for the actual electricity they produce, but also an extra fee for the size of their power plants’ generating capacity, irrespective of how often it is actually needed.

So how does a new fee given by consumers to the owners of existing coal, gas and hydro generators somehow convert into a saving for consumers?

We went digging to find out.

The so-called benefits of a capacity payment are based on a model that doesn’t actually model a capacity payment

The $1.3 billion benefit is cited by the Energy Security Board (ESB) as the saving consumers would make due to implementation of the capacity payment.

It was calculated by energy market modeller, National Energy Resources Australia (NERA).

Yet NERA didn’t actually model a capacity payment at all.

The claimed saving flowing to consumers isn’t actually a saving on their electricity bills

Instead, they modelled the existing market structure in the National Electricity Market (NEM) where generators only receive revenue for the electricity they generate, rather than their installed capacity.

They then played around with the maximum price a generator could potentially receive for its generation to see how this might impact on the amount of power plant capacity that investors wished to build or retire, and the amount of electricity demand that was subsequently unable to be met due to a lack of sufficient generating capacity.

The claimed $1.3 billion saving flowing to consumers from the capacity payment isn’t actually a saving on their electricity bills.

Rather, it is an estimate of the value to consumers from reduced power outages that comes from playing around with the maximum market price cap in NERA’s model, plus some aggressive assumptions about the exit of coal.

NERA modelled two scenarios and took the “saving” to be the system cost difference between the scenarios:

- “Capacity market” pathway: Market price cap increased by 42% from its current $15,000 per megawatt hour (MWh) to $21,247/MWh. Coal plants are assumed to exit in line with the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) Step Change Scenario with remaining thermal plants exiting in line with AEMO’s Central Scenario.

- Current pathway: Market price cap reduced by 50% from its current $15,000/MWh to $7,500/MWh. Three coal plants (Vales Point, Gladstone and Yallourn) are assumed to exit one year earlier than dictated by AEMO’s Step Change Scenario, with none of these exits anticipated by the market.

In the scenario which is supposed to represent our current pathway, NERA assumes that Vales Point and Gladstone power stations completely ignore their obligations to give 3½ years notice of closure and abruptly shut the plants sometime between around 2022 and 2024 – giving no notice to the market. Meanwhile Yallourn power station squelches on their deal with the Victorian Government to shut in 2028 and instead shuts potentially as early as 2024, once again with no notice to the market.

The NERA model finds that when the maximum price a generator could earn is increased by 42% (“capacity market” pathway), more capacity comes online compared to a situation when the market price cap is reduced by 50% (current pathway). This leads to higher Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) costs and more outages in the current pathway scenario.

It assumes Vales Point and Gladstone completely ignore their obligations to give 3½ years notice of closure

When a very rapid exit of coal is also thrown into the current pathway scenario, voila! – even more outages unfold. The outages are costed at $21,247 for every megawatt hour that isn’t satisfied, and procuring reserves from RERT is costed at $21,246/MWh.

This model makes the higher price cap scenario look better than the lower price cap scenario – because the higher price cap scenario leads to lower RERT and unserved energy costs.

Result? The Herald Sun newspaper tells readers they’ll save $1.3 billion from paying generators a guaranteed income independent of how often they are needed.

But is this realistic?

A model of a world that doesn’t exist

Firstly, what evidence has the ESB uncovered to show that investors will discount the potential maximum price they might earn by 50% in the current pathway?

The current market price cap is $15,000/MWh, which means there’s a large reward on offer to ensure capacity is available when demand is high and to avoid outages. This is much higher than the $7,500/MWh assumed.

In 2019, prices in the NEM exceeded $7,500/MWh a total of 30 times, in 2020 it was 22 times, and in the first six months of 2021 it exceeded $7,500/MWh a total of 10 times. Why is it assumed that prices do not exceed $7,500 when they most clearly do?

The ESB pretty much admits it doesn’t have any evidence for this 50% discount. In the Final Advice to Energy Ministers Part B, the ESB says that they:

“do not have clear quantification of the extent to which potential investors in low capacity factor dispatchable capacity discount spot prices above $300/MWh”.

Secondly, is it valid to assume coal generators exit at the rate of step change, or even faster?

It’s true that over the past few years, new wind and solar construction commitments have been faster than envisaged for the first few years of the Step Change Scenario, pushing out coal as well as gas. However, wholesale power prices whenever it is sunny or windy have fallen dramatically in the last few years. These are likely to remain below the levels required to support the financial viability of new wind and solar projects for the next few years.

Coal power plants face challenging profitability over the next few years

In addition, there are no policy mechanisms currently in place across the NEM which would make up for these low wholesale power prices to force further curtailment of coal and gas in line with AEMO’s Step Change Scenario.

Yes, the NSW Government has an ambitious plan to roll-out more renewable energy. However, the other states’ measures to deliver additional renewable energy capacity are mainly aspirational in the case of South Australia and Tasmania, or limited to a few hundred megawatts each in the case of Victoria and Queensland.

It is known that coal power plants face challenging profitability over the next few years. But the withdrawal of some coal capacity in the short-term will almost certainly help many of the remaining plants stay online. This makes the accelerated coal exit assumption in NERA’s current pathway unlikely.

In sum, Energy Ministers are being told to implement a radical change to the NEM, forcing consumers to pay conventional generators a guaranteed income based on a consumer savings figure plucked out of thin air, which market information from just the last six months shows is not true.

The real world Australian experience of a capacity payment

Real world experience from the Western Australian (WA) market shows capacity markets can leave consumers facing very large capacity payment fees with little benefit in improved reliability.

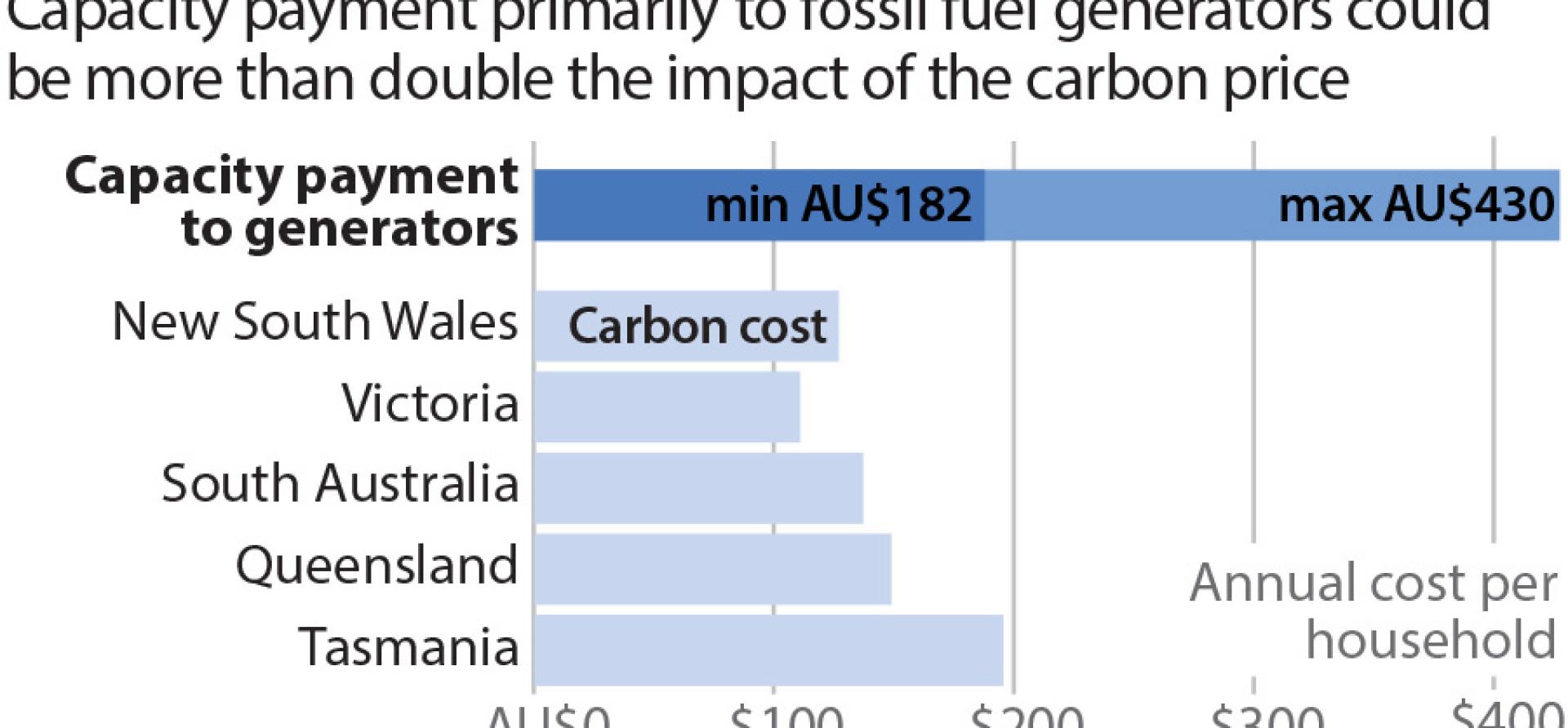

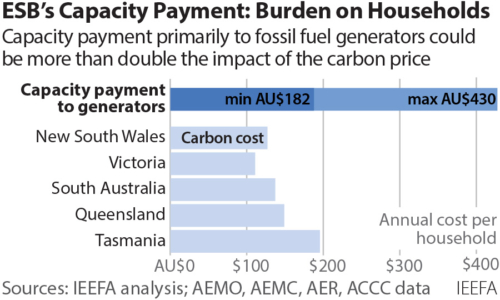

Households would face a new cost on their power bills of between $182 to $430 per year

We estimated that if the WA fees were to be replicated in the NEM, households would face a new cost on their power bills of between $182 to $430 per year. Adding some perspective, the impact of the carbon price across the main NEM states of Victoria, Queensland and NSW was far less at between $112 to $150 per year.

Back in 2014, a Liberal Government review of the WA electricity market posed the question: “Why is the cost of supplying electricity to retail customers [in WA] so high that it requires a significant taxpayer subsidy to keep tariffs at levels comparable to those in other Australian states?”

It noted that while costs of network provision in WA were lower than in the NEM,

“comparisons of generation costs with other Australian states which, while taking into account differences in underlying fuel costs and the size and conversion efficiency of power stations, show that the generation costs passed through to retail tariffs in Western Australia are significantly higher than in other states.”

The review was quite clear on where the fault lay, stating,

“The RCM [Reserve Capacity Mechanism]… appears to be a major contributor to the high generation costs in the SWIS.”

It noted that WA’s energy plus capacity payment market design had,

“resulted in customers paying for substantially more capacity than necessary to meet design standards for system security.”

In its final options paper the WA review concluded,

“Comparison of the two options for reform of the wholesale electricity market indicates clearly that retaining the capacity plus energy market in Western Australia results in higher costs than moving to the energy-only market arrangements of the National Electricity Market.”

Ultimately WA baulked at adopting the NEM’s energy-only market design not because it wasn’t a better option, but because it would involve considerable disruption for existing market participants in the process of transitioning to the new market.

It is important to recognise that once we go down the path the ESB is recommending, justified by its rather creative piece of modelling, it is extremely difficult to go back if it turns out to be wrong.

On the 20th September Energy Ministers are being asked to give the ESB the go-ahead on implementing a capacity payment. This is without either the ESB or Minister Taylor providing even a rough quantification on how much households and business will be expected to pay generators in capacity fees.

If Minister Taylor and the ESB can’t answer this very basic and fundamental question then we have to ask, is this really about protecting consumers? Or is it more about protecting the financial interests of coal-fired power station owners?

This article first appeared in Renew Economy.