IEEFA: Ceasing offshore gas exploration permits critical to cut Australia’s emissions

Australia has been dragging its feet on climate policy for decades, and is among the last in many global climate policy rankings.

While just having announced its net-zero pledge prior to COP26, the plan seems heavily reliant on technologies (some of which are unproven) rather than fundamental policy shifts.

Australia must inevitably shift to a more pragmatic ambitious climate policy to cut emissions.

This inevitability is about reputational embarrassment on the global stage, and avoiding serious economic, environmental, and financial risks for the country.

The high-emitting offshore gas sector can play a vital role in Australia’s transition from fossil fuels.

To date however, the government seems to be using its administrative power to back this industry, not curtail it.

Australia’s “investment climate” is not climate-friendly

Historically, Australia’s resource-intensive economy has been heavily dependent on foreign investment which has massively increased since 2000.

This may change however, with Australia’s climate agnosticism likely leading to the flight of landed capital.

Institutional investors are increasingly urging for a lower emissions future with almost half of all global assets under management (US$43 trillion) now linked to net-zero emissions with an ESG focus. And sovereign rating agencies’ have signalled their impatience for states not calculating in climate risk.

Being a climate laggard when investment portfolio decarbonisation is gathering momentum will lead to a higher cost of capital and consequently, capital departing Australia to less climate-risky destinations.

Disastrous environmental effects will translate to economic losses

Australia is experiencing extreme weather events including more extreme droughts, bushfires and flooding due to climate change.

At the end of the day, this will translate to economic impacts – in coastal areas where insurance costs for infrastructure will increase, or in the tourism industry being disrupted by coral reef bleaching – adding a near $3.4 trillion loss in GDP by 2070 in present value terms.

Offshore oil and gas sector is critical to Australia’s climate policy shift

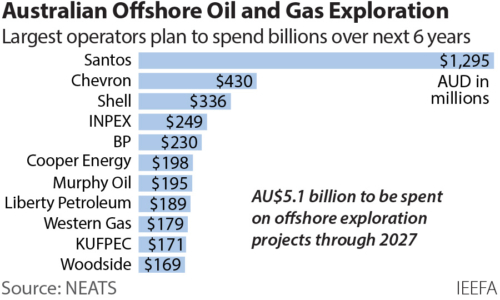

The Australian energy industry is heavily dependent on offshore gas with 70% going to the LNG industry and reserves 3 times larger than onshore.

One of the key initial steps Australia could take to reach net-zero emissions would be stopping the development of new offshore gas projects, given their significant contribution to scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, nationally and globally.

All offshore oil and gas projects in Commonwealth waters are directly administered by the federal government’s National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA), enabling uniform and timely policy design and implementation. (This is not the case in the onshore sector, where states administer projects.)

This centralised regulatory structure gives the Australian Government an agile lever to put the brakes on the country’s massive emissions, and reduce the issuance of offshore oil and gas permits by NOPTA.

Exploration permits in particular warrant attention as they are potentially the “new oil and gas” development projects which the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its flagship report “Net Zero by 2050” said must stop, immediately.

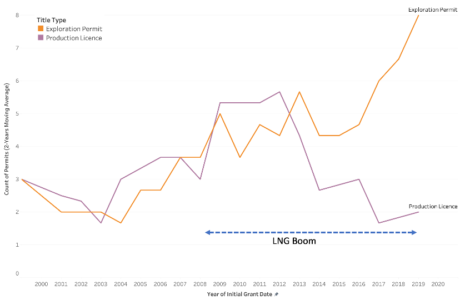

It is stark to learn that permit issuance trends reveal NOPTA has been increasingly issuing exploration permits – far more than production licences – over the last decade, and the gap widened last year.

Figure 1: Offshore Exploration Permits Vs. Production Licences Issued in 21st Century

Source: NEATS, IEEFA Analysis

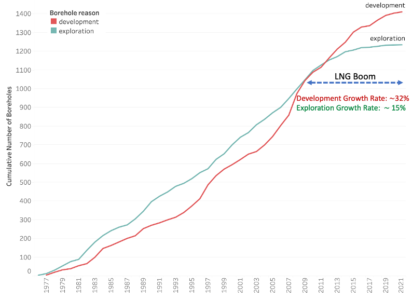

In contrast, exploration wells grew at half the rate of the increase in production wells over the last 12 years, despite the government’s ongoing encouragement for exploration.

Figure 2: Exploration Wells Vs. Development Wells – Offshore Drilling Trends (1975-2021)

Source: NOPMIS, IEEFA Analysis

This unprecedented disparity in Australia’s offshore drilling dynamics arguably suggests the industry itself may not have the government’s confidence in large-scale offshore expansions or another LNG boom, and is in fact embracing the inevitability of the energy transition.

Betting on exploration projects will mean costly stranded assets in the near future, so the industry is generating as much cash as they can now from existing commercialized fields, considering global gas demand will peak in 2025 according to the IEA.

Going forward

Australia has already been affected by the consequences of climate change, but it is just the beginning.

More stringent carbon taxes, levies such as Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), lower sovereign credit ratings, and more extreme weather events will increase pressure on Australia’s economy.

Although inaction could be an option for Australia, it would not be costless.

Industry dynamics and global financial movements signal the inevitability of energy transition. There is no time for complacency in climate policy with the world already on course to surpass 1.5°C.

For Australia, the best time to make serious climate action was decades ago, but the next best time is now.

Using governance power to curtail offshore gas exploration would be a mighty first step.

Milad Mousavian is an energy analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA)

Related articles: