IEEFA: The cash hit-list to counter climate change

I was struck by the image of the G20 leaders tossing coins over their shoulders into the Trevi Fountain to make a wish. That pretty much sums up what members of that group will be left with – not least our own PM – if they don’t get moving on providing an adjustment mechanism to counter climate change.

But what might such a mechanism look like?

The problem, as always in economics, is demand and supply.

On the demand side, China, the largest absolute emitter, is experiencing an energy crisis that is causing it to build more coal-fired power stations. President Xi has sent his own signal. He won’t even be in Glasgow. China’s fossil-fuel demand is rising, not falling.

On the supply side, resource producing countries can’t dig it out fast enough. Australia is China’s biggest supplier of iron ore for its blast furnaces and coal to run them. And Russia, Indonesia, India, Brazil and the Middle East are on the same page.

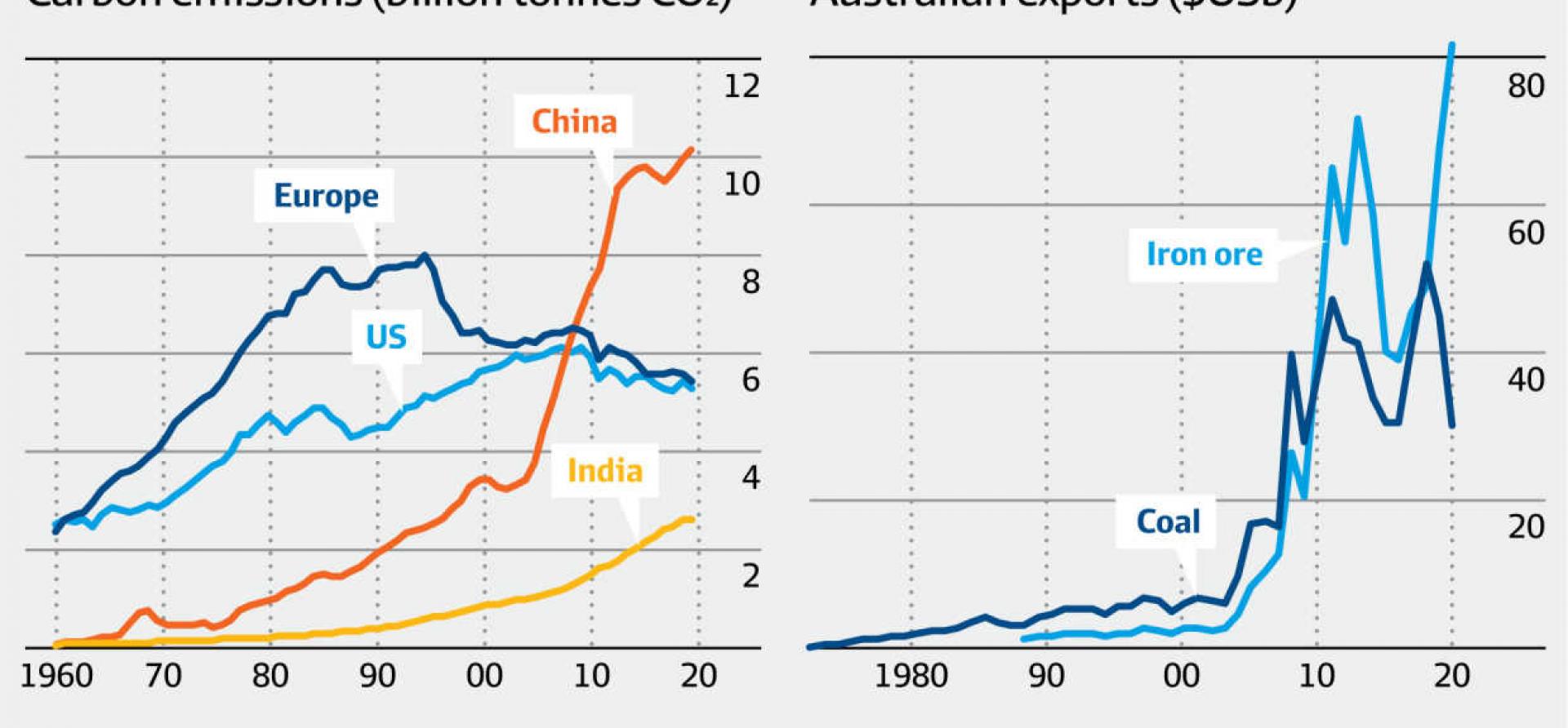

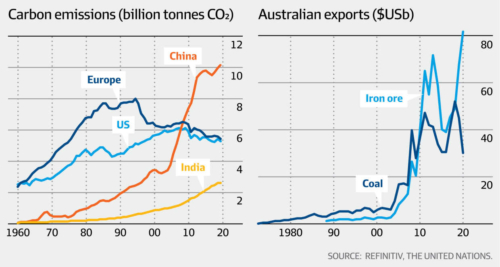

The chart below from Refinitive and the United Nations encapsulates the essence of the issue. The feeding of iron ore and coal into the China boom from Australia is evident in the chart.

The other resource supplier countries have a similar profile to this. China’s C02 emissions from the demand side are now so large that they are the equal of Europe and the US combined. From this base, China will be powering an economy growing at about 4% per annum.

To be fair, China has recently introduced an emissions trading scheme designed to reduce the intensity of emissions, but not the absolute volume. It helps to walk to the precipice more slowly, perhaps, like gas fracking versus coal has done in the U.S.

But the reality is that the world is not going to get far on global warming if China isn’t committed to rapid action. Unfortunately, it seems that China isn’t.

All China’s initiatives in recent years signal their intentions. The Dual Circulation Strategy announced this year clarifies the logic of what it has been building towards, in full view of a complacent West.

The world is not going to get far on global warming if China isn’t committed to rapid action

As global tensions rise, Dual Circulation is designed to switch more towards domestic demand for Chinese production (not Western non-resource imports), while external trade through the Belt and Road Initiative will be stepped up.

The root of this aspect of global warming can be traced back to globalisation: the welcoming of China into the World Trade Organisation in 2001 (turning it into the manufacturing hub of the world) in the belief that they would become a part of the rules-based global economic order. The West could outsource manufacturing and move further up the value-added chain.

But the true dividend is a climate catastrophe. The dilemma is what to do now.

China’s argument is that its per-capita emissions are less than the West’s and, therefore, the West must do more to make room for it. A bit like the Titanic, which didn’t have enough lifeboats and women and children were given preference.

Of course, men could have jumped into the boats and sunk the lot, arguing that they had the same rights too. Fortunately for the women and children, they didn’t. Today’s children won’t be so lucky.

There seems to be an element of global disbelief about the danger for the children of today. Rescue ships are on the way. Carbon capture and hope.

Seriously.

The new OECD Secretary General, Australia’s Mathias Cormann, has pointed out that which is consistent with all the OECD has said before: the most efficient way to achieve 2030/2050 targets is a global carbon pricing system that creates the incentive mechanisms for adjustment.

Absolutely right.

But China on the demand side and all the resource supplier countries – not least Australia, where politicians wear it as a badge of honour – have made it clear that this is not going to happen.

Europe and the U.S. would need to do a lot more in Glasgow to produce a mechanism that forces the issue with unwilling global partners.

The most efficient way to achieve 2030/2050 targets is a global carbon pricing system

What a marvel of marketing that a good chunk of Australian electors buy the idea that carbon capture, plus $20 billion spending to pick winners for future technology, will get us to net zero with no price signals. No Australian government will be putting the brakes on our Scope 3 emissions through a moratorium on new developments.

Indeed, the premiers of Queensland and Western Australia gloat over their recent approvals: Queensland’s massive Galilee Coal Basin (one of the largest coal reserves in the world) and WA’s Scarborough gas field. These premiers aren’t accepting any out-of-state parochial views from the rest of Australia or indeed the world. Global warming apparently will have no effect on these special places, nor in any of the other resource-supply countries.

In the chart, Europe and the U.S. look as if they have done well in cutting emissions – but the truth is otherwise. By choosing 1990 as the Kyoto base year, Europe was able to take credit from the collapse of East Germany, rather than tough binding climate policies. Then from 2009, the global financial crisis helped the next emissions dip in both the US and Europe. The gas fracking boom too helped improve the US profile.

Given the politics blocking everything right now, Europe and the U.S. would need to do three things.

First, set a (phased) price on carbon in their own countries that would bring about the required adjustment if adopted by all.

Second, since the unwilling won’t adopt those prices, Europe and the U.S. will need to impose (phased) carbon price equalisation taxes on all imports from the unwilling.

Third, provide substantial aid to developing countries for the finance needed to respond to these new price signals.

Glasgow should be judged on whether the U.S. and Europe can bring about something like this.

Without it, we are left with that image of the G20 leaders tossing coins into the Trevi Fountain in the hope that the Tooth Fairy will bring about a technology revolution, with no price incentives to do so.

IEEFA guest contributor Adrian Blundell-Wignall writes on the world economy and is a former director of the OECD.

Related articles:

IEEFA Update: Global methane pledge needs action, not transition

IEEFA: COP26 needs to focus on renewables not fanciful technology